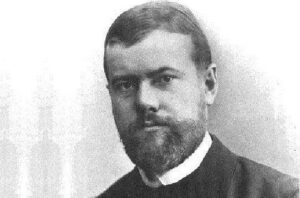

The BEST: The Protestant Work Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism

Summary: One of sociology’s early classics, The Protestant Work Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism by Max Weber ambitiously sets out to explain the prosperity of Protestant countries. However, Weber’s magnum opus is significant for the religiously curious specifically because it demonstrates how religious doctrine can have a profound impact on both culture and economics.

The central thesis that Weber attempts to prove is that the Calvinists, Methodists, Baptists, Quakers, and Pietists developed a work ethic independent of consumption. The sects were simultaneously ascetic and industrious. The cultures produced by the Protestant reformation valued work and productivity for its own sake; consumption and hedonism were frowned upon. The religious development of the Protestant Work Ethic originates in the Calvinist concept of predestination. Calvin preached that God already knew who was among the elect, or saved, and they were predestined to enter heaven already. The pious could not change their position. However, Church luminaries implored them to develop confidence in their position among the elect. The best way to develop this religiously mandated confidence was to contribute to the recognizable economic success of God’s community. Thus, hard work, frugality and the amassing of wealth became the religious life aim of these Protestants.

Weber presents the words of Benjamin Franklin in “Advice to a Young Tradesman” as a prime example of this Protestant philosophy, “Time is money… he that can earn ten shillings a day by his labor… and sits idle half of that day… has really thrown away five shillings.” Furthermore, “Credit is money,” and “money has a proliferation power.” Franklin goes on to explain that wasting a coin is like slaughtering a cow – neither can produce future offspring. The uniqueness of this wisdom is that it speaks of economic achievement on its own terms, while at the same time demurring consumption.

Why this is The BEST: While the Torah world may have little use for the theology of the Protestant sects, the idea that religion is a primary driver of culture and that culture is a primary factor in the economy should concern any community leader who considers how religious doctrines impact the culture which we all inhabit. We would be naive to think that our own halakhic and hashkafic discussion on Torah im Derekh Eretz versus full-time Torah study as a universal ideal will have no impact on culture or economy. The idealization of exclusive Torah study and the tandem disapproval of those who work will certainly create its own economic outcomes and pressures. Just as Protestants became industrious in response to the preaching of their leaders, so too economic hardships would logically follow from the prejudice against secular employment. Such economic hardships may in turn lead to the negative social outcomes of poverty, such as crime, anxiety, divorce, and depression.

One additional insight of Weber’s deserves mention. He attempted to determine the difference between Church and Sect. The former being an institution that speaks with authority and which must serve all the people. The Sect, on the other hand, is the community of the chosen, whose members are admitted by virtue of a voluntary mutual decision by community and individual. Freedom of conscience characterizes the self-selection of sects. For example, Quakers must respond to the voice of their own conscience above the authority of the Quaker movement or sect. This fealty to personal conscience was an important factor in the anti-authoritarian nature of American democracy. In short, the Unites States Constitution is a direct outgrowth of Protestant sectarianism. The particulars of faith may be less interesting to the Jewish Community than the methodology of tracing the origin of religious ideas into the formation of national governance.

Weber established the methodology that traces the path from sermon to everyday culture, as evidenced by his demonstrating how the pithy common sense of Benjamin Franklin emerged from Quaker sermons. Certainly, the religious virtues of envisioning future outcomes (see Kohelet 2:14 and Avot 2:9) and being vigilant for the consequences of actions recommend that we study Weber’s methodology.

Rabbi Andrew Rosenblatt serves as the Senior Rabbi at Congregation Schara Tzedeck in Vancouver British Columbia, Canada

Click here to read about “The BEST” and to see the index of all columns in this series.