LETTER: Judaism Is About Love—and Jealousy?

To the Editor:

My dear friend, R. Yitzchak Blau, penned an insightful and comprehensive review of Rabbi Dr. Shai Held’s new volume, Judaism Is About Love (TRADITION, Spring 2025). I write to comment on one small passage in the review where R. Blau writes:

Before reading this book, I had never considered that God’s thirteen attributes of mercy begin with He is “merciful and gracious” and then list what He does “extending steadfast love to the thousandth generation and forgiving iniquity” [as Held suggests in his book]. This distinction between God’s being and doing can explain why imitatio Dei does not apply to the divine trait of vengeful wrath, since that aspect is not included in the essential attributes of God.

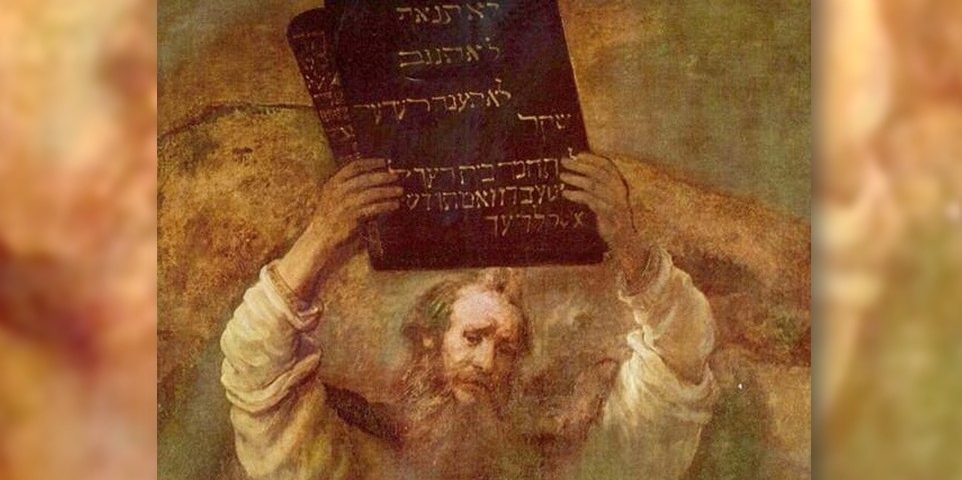

This is a wonderful idea in theory, but fails the test of biblical coherence in the face of other closely related and salient passages. In the Decalogue, just a few chapters prior to the verse R. Blau cites (Exodus 34:7), the Torah describes God as being an El Kana—a zealous or jealous God. The term kin’a in the Bible is often synonymous with vengeance and sometimes appears hand in hand with the quality of nekama as we find in the beginning of the book of Nahum: “The Lord is a jealous and avenging God; the Lord takes vengeance and is filled with wrath” (El kano ve-nokeim; 1:2). A few short verses after God introduces the Thirteen Principles of mercy in Exodus 34, He immediately reminds the Israelites not to enter into a covenant with the nations that they will encounter in the land of Israel and forbids worship of their idols for God, “For God’s name is ‘Jealous One’ (kana), He is a jealous (kana) God” (34:14). Rashi emphasizes: “God is jealous/zealous to punish and does not relent. That is [the meaning of] every expression of jealousy [in connection with God]. It means that He is steadfast in His superiority [over other deities] and exacts retribution upon those who forsake Him.”

This is a wonderful idea in theory, but fails the test of biblical coherence in the face of other closely related and salient passages. In the Decalogue, just a few chapters prior to the verse R. Blau cites (Exodus 34:7), the Torah describes God as being an El Kana—a zealous or jealous God. The term kin’a in the Bible is often synonymous with vengeance and sometimes appears hand in hand with the quality of nekama as we find in the beginning of the book of Nahum: “The Lord is a jealous and avenging God; the Lord takes vengeance and is filled with wrath” (El kano ve-nokeim; 1:2). A few short verses after God introduces the Thirteen Principles of mercy in Exodus 34, He immediately reminds the Israelites not to enter into a covenant with the nations that they will encounter in the land of Israel and forbids worship of their idols for God, “For God’s name is ‘Jealous One’ (kana), He is a jealous (kana) God” (34:14). Rashi emphasizes: “God is jealous/zealous to punish and does not relent. That is [the meaning of] every expression of jealousy [in connection with God]. It means that He is steadfast in His superiority [over other deities] and exacts retribution upon those who forsake Him.”

The juxtaposition of presenting God’s essence of one of jealousy and vengeance together with His essence as one of mercy and compassion may yield a different theological statement emerging from the aftermath of the sin of the Golden Calf. Prior to that event, God presented Himself as a God of pure justice and exacting truth. In the Decalogue, the grave sin of worshiping other Gods should yield God’s absolute retribution as God is ready to mete out in Exodus 32 with the destruction of the Israelites. The entreaties of Moshe and the change in attitude of the people as recorded in the following chapter of Exodus move God to introduce the notion that His justice and vengeance can be tempered with His overwhelming mercy and compassion. To use rabbinic imagery, God’s move from the throne of justice to the throne of mercy (Leviticus Rabba 29:3). However, the two continue to exist as essential qualities of the Ribbono shel Olam. (This juxtaposition is also central to the passage in Deuteronomy 4, read on Tisha B’Av morning, which includes Moses’ statement that God is an El Kana and will exile the Jewish people, but also that God is an El Rahum and thus will restore the Jewish people when they seek out His presence.)

It may be more accurate to thus suggest that in this divine move to temper the strict justice and vengeance of God the rabbis saw the opening to privilege God’s essential qualities of mercy over God’s other essential qualities in an act of imitatio Dei taken one step further.

Rabbi Nathaniel Helfgot leads Congregation Netivot Shalom in Teaneck.