Orthodoxy and the Scholem Moment

Today, 28 Shvat, is the 40th yahrzeit of Prof. Gershom Scholem. To mark the occasion we are republishing this column by Zvi Leshem exploring the slew of books and studies recently published on the life and legacy of the path-breaking Kabbalah scholar. Leshem suggests that understanding this phenomenon can help us understand some major trends in contemporary Orthodoxy.

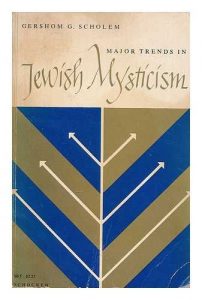

I begin with a confession. When I was hired to direct the Gershom Scholem Collection for Kabbalah and Hasidism at the National Library of Israel, close to a decade ago, I had already read a fair amount of Scholem’s research, including his 1941 classic Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism, which I first read as an undergraduate, and various articles and parts of other books. I thought that I had a reasonable understanding of Scholem the Kabbalah scholar. However, what did I know about the multi-faceted personality behind the tomes? Of him, I knew very little other than having briefly glanced through his rather curious autobiography From Berlin to Jerusalem1 and David Biale’s Gershom Scholem: Kabbalah and Counter-History. Of course, as many of us know, the best way to learn is to teach, and almost immediately I received an invitation to speak about Scholem at a study day for rare book librarians. My session dealt with Judaica scholars who had also been librarians, including Scholem and his sometime nemesis, R. Reuven Margoliot. R. Margoliot, who in addition to the very many books he authored or edited, also held a day job, serving as librarian at Tel Aviv’s municipal Torani Library, Sifriat HaRambam, between 1934 and 1971. I had discovered that Scholem was also a librarian. What else? In order to prepare I began to delve into what seemed like an almost endless amount of material. Besides the autobiography and Biale’s book, there were Scholem’s diaries, his correspondence, seemingly endless articles about him, a couple of Ph.D. dissertations, and numerous interviews as well. To say nothing of the unpublished archival material. (In the interest of full disclosure – ten years on I have still not read everything!) However, not only did this scholar/librarian, completely revamp the Dewey Decimal System in 1927 to make it compatible with large Judaic collections, he was also seen by many in Israel and beyond as one of the greatest Jewish intellectuals of the twentieth century. Others saw him as a philosopher/theologian of great significance. With so much material, I asked myself, how can it be that there was no single biography about Scholem? Would I need to write it myself?

Fortunately not. Recent years have seen an explosion of publications about Scholem, including several full-length monographs and biographies, in English, Hebrew, and German. His autobiography has appeared in numerous languages and more volumes of his diaries, poems, and letters have appeared, some of these in multiple languages.2 Not only that, but we now have a biography of his older brother, the German Communist leader and Holocaust victim Werner, and a full-length book about the Scholem family in the context of early twentieth century German Jewry! Many of these books have received a place of prominence, reviewed in literary, scholarly, and other journals, at academic conferences, and book fairs. What is particularly notable is that they barely touch on Kabbalah or Jewish mysticism, the topics that Scholem devoted his life to researching, and instead focus on teasing out Scholem’s philosophy and theology from between the lines of his research works, or from his diaries and letters. It is also worth noting that his classic books in Kabbalah research are constantly appearing in new translations and editions, not only European, but in East Asian languages as well. Lastly, his most famous work, Major Trends, finally has a Hebrew translation, close to eighty years after its initial publication. In the realm of journalism, op-ed pieces about Scholem regularly appear in Israeli newspapers and in American publications such as The Jewish Review of Books. It would seem that we are indeed in the midst of what could be termed a “Scholem Moment.”

This leads us to two questions: what is the reason for this sudden fascination with Scholem in recent years, and perhaps more importantly for those reading this article, who cares? That is to say, why is Scholem, often described (to his chagrin) as a “secularist” (in his opinion he could not be called “secular” since he had always believed in God), and scathingly attacked by some Orthodox thinkers for a variety of heresies, important to us in the Orthodox world? As we shall see, these two seemingly disparate questions may actually be interrelated and shed light on each other. They may even help us understand certain current spiritual trends in our own community.

There is no doubt that the renewed interest in Scholem and his work is related to world-wide trends of “New Age” spirituality and in, the Jewish world, the popularity of Kabbalah and the phenomenon of “neo-Hasidism” in its many formations, both Orthodox and liberal. Scholem was essentially the first person to present the concepts of the Kabbalah to a wide audience and in doing so influenced a range of thinkers, including literary figures such as Jorge Luis Borges and Harold Bloom, and philosophers like Jacques Derrida and George Steiner. Through them and others, Kabbalistic symbolism, linguistic theory, and other aspects of Jewish mysticism penetrated wider audiences. If Buber was almost singlehandedly responsible for introducing Hasidism to the West, we could say the same of Scholem for Kabbalah proper. While this “outreach” has been advanced in recent decades by the work of Moshe Idel and others, Scholem planted the seeds, and even Idel’s strong disagreements with Scholem’s theories serve to reinforce the latter’s presence in spiritual dialogue, scholarly and otherwise.

Of course, politics plays a role in the Scholem moment as well. It is only human nature to try to demonstrate how great people (conveniently dead and unable to respond) agreed with you and your ideology. Scholem, after his Aliyah in 1923, was a leading member of the radical Left Brit Shalom movement, which advocated for a binational state for Jews and Arabs. Later, after moderating his views to the mainstream Left, he was nonetheless a signature to the 1967 intellectuals’ letter opposing the annexation of the recently captured territories. This serves to make him a bit of a poster child in the current Israeli political deadlock. For those who raise the specter of the demise of the “two state solution” due to the proliferation of settlement in Judea and Samaria, Scholem has achieved almost canonical status as a tanna demisaya.

Gershom Scholem: Scholar and Cultural Figure

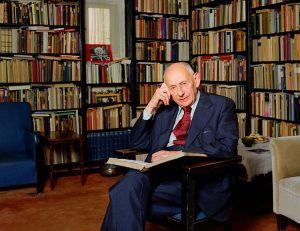

Gershom Scholem was born in Berlin in 1897 to an upper middle class semi-assimilated Jewish family. He earned a Ph.D. in Munich in 1922, writing on Sefer HaBahir, and arrived in Mandatory Palestine the following year to head the Judaica Department of the Jewish National Library. In 1925 he began to teach in the newly established Hebrew University, becoming a full-time lecturer in 1927, and later full professor. During his long career Scholem published over 600 books and articles in Hebrew, German, and English, on nearly all aspects of Kabbalah and Jewish mysticism. He died in 1982.

Scholem, in his lifetime, was not only the consummate scholar of Jewish mysticism, but also stood at the center of a circle of Jewish intellectuals that included figures as diverse as S.Y Agnon, Martin Buber, Zalman Shazar, Ben Zion Dinur, Ernst Simon, and Samuel Hugo Bergman (who arranged for his visa in order for him to work at the National Library). Scholem’s home, with its tremendous library, was a popular meeting place, and he was a very generous book loaner. In his later years he was also in demand as a lecturer on the international scene. This included return trips to Germany, where, despite his strident criticism of the postwar “German-Jewish Dialogue,” he achieved almost superstar status which has only grown since his death. For Scholem this status enabled r him to defend Israel in the international arena. Note should be made of his annual lectures at the Eranos conferences on religion in Ascona Switzerland, between 1949 and 1979.3 There, Scholem rubbed shoulders with non-Jewish scholars as well, including some with dubious pasts, such as C.J. Jung and Mircea Eliade. Regarding Jung, Scholem had agreed to meet with him after hearing from German Reform rabbi and Holocaust survivor Leo Baeck that Jung had repented for his early flirtation with National Socialism, although in a later correspondence Scholem expressed regret regarding his decision. These meetings, which led to strong criticism of Scholem, helped to spread his influence well beyond the somewhat provincial realm of Judaic Studies to the international arena of Religious Studies and helped to launch the discipline now known as “Comparative Mysticism.”

Scholem, in his lifetime, was not only the consummate scholar of Jewish mysticism, but also stood at the center of a circle of Jewish intellectuals that included figures as diverse as S.Y Agnon, Martin Buber, Zalman Shazar, Ben Zion Dinur, Ernst Simon, and Samuel Hugo Bergman (who arranged for his visa in order for him to work at the National Library). Scholem’s home, with its tremendous library, was a popular meeting place, and he was a very generous book loaner. In his later years he was also in demand as a lecturer on the international scene. This included return trips to Germany, where, despite his strident criticism of the postwar “German-Jewish Dialogue,” he achieved almost superstar status which has only grown since his death. For Scholem this status enabled r him to defend Israel in the international arena. Note should be made of his annual lectures at the Eranos conferences on religion in Ascona Switzerland, between 1949 and 1979.3 There, Scholem rubbed shoulders with non-Jewish scholars as well, including some with dubious pasts, such as C.J. Jung and Mircea Eliade. Regarding Jung, Scholem had agreed to meet with him after hearing from German Reform rabbi and Holocaust survivor Leo Baeck that Jung had repented for his early flirtation with National Socialism, although in a later correspondence Scholem expressed regret regarding his decision. These meetings, which led to strong criticism of Scholem, helped to spread his influence well beyond the somewhat provincial realm of Judaic Studies to the international arena of Religious Studies and helped to launch the discipline now known as “Comparative Mysticism.”

It is impossible in this context to attempt even the most cursory summary of Scholem’s scholarship; the published record is too extensive, and even more material remains unpublished almost 40 years after his death. In fact, in the past two years alone, his full-length Hebrew monograph on the Sabbatean movement was published from archival material, and a full-length book on Hasidism is currently in preparation. Although many of Scholem’s assumptions and theories have been questioned by his students and their students (my generation), his writings, often defended by other scholars, retain canonical status. We could say that in the world of academic Kabbalah study Scholem, is the mara de-shmatita – he can be questioned and debated, but never ignored. Buber famously described him as one who had single-handedly created a new academic discipline and today it flourishes in the academies of Israel, North America, and Europe, with influence as far away as Tokyo. Additionally, Scholem’s early research was largely given over to bibliographical studies and manuscript work. This more “technical” research, which provided the basis for his later, more content-oriented studies, still stands independently as a major edifice enabling all future scholarship in the field.

Scholem also singlehandedly built the world’s greatest collection of literature pertaining to Jewish mysticism, Kabbalah, Hasidism, Jewish messianic movements, and related fields. This collection, which is comprised of both primary sources and research materials, numbered some 25,000 items when it was transferred to the National Library of Israel after Scholem’s death. Included in the collection were some 5,000 rare books of various types and hundreds of photographic copies of Kabbalistic manuscripts from libraries throughout the world that Scholem painstakingly acquired over decades of effort. Later the collection was augmented with contributions from some of Scholem’s leading students: Isaiah Tishby, Rifka Schatz-Uffenheimer, and Chaim Wirszubski. Today, the collection, now numbering some 35,000 items, serves as the intellectual hub for scholars of Kabbalah worldwide, both the Israelis who visit it on a daily basis and international scholars who spend their sabbaticals or summers there. When I say scholars, I refer not only to academics but also to those who we refer to as “independent Haredi researchers” – some of our most loyal patrons. This is a unique multi-cultural meeting place, where it is completely common to see a Mea She’arim resident with long payot arguing over a passage from the Zohar or Lekutei Moharan with a “secular” professor (male or female). I would mention as well Scholem’s pivotal role in the Otzrot HaGolah project in 1946, in which he spent an emotionally devastating year in post-war central Europe salvaging Jewish books that the Nazis had plundered, and whose owners had perished, or communities destroyed. Due in large part to Scholem’s (admittedly controversial) efforts, many thousands of these books found their way to the National Library where they are now available for use by any reader.

Scholem’s students were far from his clones. They often differed with him not only on scholarly points, but also religiously and politically. The primary challenge to Scholem’s Kabbalistic worldview came from Moshe Idel, most notably in his 1988 Kabbalah: New Perspectives. Some of Scholem’s closest students, including Yosef Ben Shlomo, Rivka Schatz, and Yehuda Liebes were prominently associated with the Greater Israel Movement, a position diametrically opposed to his own. Others, including Ephraim Gottlieb, Moshe Halamish, and Amos Goldreich were strictly Orthodox. Today the ranks of Kabbalah researchers in Israel include many rabbis, not a few with beards and payot as well.. This in turn is connected to the blurring of lines between the researcher and his research and to the cultural-religious trends that I shall return to shortly.

In addition to Scholem’s influence as a teacher/mentor, and hub for Jewish intellectuals, Scholem was also an impressive correspondent. His published correspondences with international figures includes Hannah Arendt, Theodore Adorno, Leo Strauss, Joseph Weiss, Morton Smith, Werner Kraft, and Walter Benjamin. Regarding the latter, I would like to note that Scholem devoted no small effort to publicizing him after his tragic Holocaust-era suicide. In addition to authoring a semi-autobiographical monograph, Walter Benjamin: Story of a Friendship, he collaborated closely with Arendt and Adorno on publishing Benjamin’s collected works. This in spite of his ideological tug-of-war with the Frankfurt School. Whereas for Scholem, Benjamin was primarily a Jew who dabbled in Marxism, for the philosophers the opposite was true. Additionally, the Scholem Archives contain significant amounts of still unpublished correspondence, including his letters with S.Y. Agnon and with R. Prof. Shaul Lieberman. Overall Scholem emerges as a pivotal figure in our understanding of Jewish intellectual trends of the twentieth century.

Scholem was among the most towering scholars of Judaism as culture and intellectual tradition—but what of his attitude to Judaism as religion and faith? Was he the young man from a fairly assimilated, middle-class Berlin family who, after reading Graetz’s History of the Jews, became obsessed with Jewish texts, Zionism, learning Hebrew, and eventually Kabbalah? Or perhaps he was more the one who fantasized about the messianic implications of his family name and, for a brief stint, was a member of the Berlin chapter of Tze’irei Agudas Yisrael. Of course there is the Scholem who in 1926 wrote to Franz Rosenzweig about the dangers inherent in the secularization of the Hebrew language. On the other hand, we have the Scholem who would admit in an interview that the “Judaism of the Kitchen” did not interest him and yet castigate Martin Buber for (in Scholem’s estimation) “probably not even fasting on Yom Kippur”! This is the same man who was makpid to maintain daily sedarim in Bible, Zohar, and the writings of Kafka.

Of course, we cannot surgically separate the disparate personalities from each other, or from the world of his research. He was a scholar who penned thousands of pages about Shabbtai Zvi while vigorously asserting that Zionism was not, and must not become a messianic movement. The man who bitterly castigated his (former) friend Hannah Arendt over her 1965 Eichmann in Jerusalem, accusing her of a lack of “ahavat Yisrael,” and yet seemingly traded places with her regarding the proper fate for Eichmann, whom she felt should be executed, which Scholem opposed.

Perhaps all of the above, which really just scratches the surface of this extraordinarily complex individual, has a lot to do with his reemerging popularity. He was apparently not merely the “accountant” keeping track of the statistics of Kabbalistic texts, as Herbert Weiner described him in his 1979 volume, 9 ½ Mystics: The Kabbala Today. Perhaps the truth is closer to the description of his student Joseph Weiss (about whom Scholem claimed cryptically to have played a role not only in his “scholarly” but also in his “spiritual” development), as one who reveals only a tefah while concealing tefahayim, regarding his own views and inner life.

But Was He Frum?

Scholem, who in his lifetime was on very good terms with many in the Orthodox community, was nonetheless subject to significant criticism from some of its members. Perhaps some bristled at the very idea of a “secular” scholar of Kabbalah, for many the “Holy of Holies” of the Torah.4 This is related to the argument (questionable from an academic perspective) as to whether an “outsider” is ever capable of fully penetrating and analyzing his subject.5 I would also add that from an Orthodox perspective, the minute we write off someone as being “secular,” usually without bothering to define the term, we have transformed them into a soft target or source that can be conveniently dismissed without paying too much attention to their actual words, positions or proofs.

Other writers took strong exception of some of Scholem’s scholarly positions, such as regarding the lateness of the composition of the Zohar, although he was hardly the first to make this suggestion, even within the Torah world.6 His view of Kabbalah as a form of “mysticism” or a sort of “Jewish Gnosticism” also aroused opposition as he was seen as sullying the holiness of the Kabbalah by comparing it to various forms of “idolatry.” Others strongly opposed his extensive scholarly interest in Shabbtai Zvi and Jacob Frank, accusing Scholem of identifying with his subjects or of seeking to promote a cultural/religious agenda based upon antinomianism.7 A related topic was his revisiting of the controversy between R. Yaakov Emden and R. Yonaton Eibeshutz. Scholem accepted R. Emden’s accusations and was attacked for this by R. Reuven Margoliot, who preferred to view the case as already being closed. On the other hand, Orthodox Rabbi Marvin S. Antelman, in his 1974 To Eliminate the Opiate based his attack on R. Eibeshutz partly on Scholem’s research and wrote to Scholem regarding his work. The book earned Antelman an invitation from the Massachusetts Council of Rabbis to stand trial for heresy. In his follow-up book Bekhor Satan: Yonatan Eibeshutz Masit u-Madiah Antelman published a letter of defense from R. Chaim Etner of the Los Angeles Beit Din. In R. Etner’s words, “Rabbi Antelman based his accusations on the writings of Professor Gershom Shalom [sic], an authority on Cabbalistic history. Professor Shalom based his writing on newly discovered documents.”8

More recently a young Sefardi-Haredi scholar, R. Ohad Turjeman, who has edited several volumes from Kabbalistic manuscripts, introduced his edition of R. Yosef Taitazak’s Malakh HaMeishiv (2009) with an essay beginning, “In this article I used…the article [of Scholem] ‘The Magid of R. Yosef Taitazak and the Revelations Attributed to Him,” in Sefunot 11. It was path-breaking in analyzing portions of the manuscript. May my article be for the illuy neshama of the great scholar, G. Scholem z”l.”

Was Scholem frum? Certainly not. Was he “secular”? Not in his own eyes. For those who require such definitions he could be considered some sort of “traditionalist,” both in practice and in his study habits. One of his close students related to me that Scholem would recite Kiddush on Friday nights “with great enthusiasm”. He was certainly a masmid as his list of publications, correspondence, and marginalia clearly attest. I once asked R. Prof. David Halivni about Scholem’s close relationship with R. Shaul Lieberman. “What at all did they have in common?” His answer, “They were both ohavei Torah”!

However the more important question is – does it really matter? The Maimonidean principle of accepting the truth regardless of its source is certainly applicable here. Does that mean that we should allow ourselves to fall into the trap of unquestionably accepting all of Scholem’s positions? Absolutely not. As always, we must engage in critical reading and analysis. Sometimes Scholem’s biases are readily apparent and grate at the ears of the pious. On other occasions it is hard not to detect a note of hubris. And as is true in any good scholarship, many of his theories have been questioned, attacked, and even overturned (at least for now) by subsequent research. But if we let ourselves off the hook too easily and disengage from Scholem the Kabbalah scholar we risk doing ourselves and our learning a grave disservice. I think that many readers will admit that until reading Major Trends they were incapable of “finding their hands and feet” in the history of Kabbalah. Perhaps Scholem can help us to integrate our (to use his friend Ernst Simon’s expression) “second simplicity,” our second level of more worldly and thoughtful innocence. Additionally, if we ignore Scholem the political/cultural figure we are in danger of limiting our understanding of the course of Jewish and Zionist intellectual history and fascinating aspects of Israel’s first decades.

Scholem and the Contemporary Orthodox Spiritual Scene

Let us return to our second question, how and why this is particularly relevant to contemporary Orthodoxy? In my opinion, several aspects of Scholem’s scholarly and cultural oeuvre, even for those who strongly disagree with his worldview or aspects of his scholarship, clearly demonstrate his importance in current Jewish academic and religious discourse.

Scholem, perhaps despite himself, has played a role in the current neo-Hasidic revival, including in its Orthodox formulations. We are used to pointing to a wide range of more overtly “spiritual” figures in this context, such as R. Hillel Zeitlin, whom Scholem held in high esteem, Rav Kook, whom Scholem idealized, R. Avraham Yehoshua Heschel, with whom Scholem corresponded, and Reb Zalman Schachter, Arthur Green, and R. Adin Steinsaltz, whose works Scholem collected. Of course one cannot ignore Martin Buber, Scholem’s major bar pelugta in interpreting Hasidic texts, who was one of the first to present Hasidism to a wide audience, and whose books on the subject are still, some one hundred years after their publication, bestsellers. Nonetheless, Scholem’s influence on the current moment should be explored as well. Paradoxically, Scholem, whose philological approach would seem to be far less “spiritual” than the literary-existentialist-dialogic thrust of Buber or the experientialist approach of Heschel, may be more palatable to an Orthodox audience. Buber, in his lovely renditions of Hasidic tales, chose to emphasize this-worldly spirituality at the expense of halakha and other more traditional Rabbinic and/or Kabbalistic elements. Scholem, in his historical/philological approach to Hasidic discourses, was seemingly less interested in contributing to contemporary spirituality, and thus had little reason to present Hasidism in a more “attractive” form than what he saw in the actual texts.9 So, while Buber’s writing is certainly more “spiritual” than that of Scholem, aspects of it may feel inauthentic to an Orthodox reader. Scholem, who on the one hand can be downright offensive,10 on the other hand leaves us with a picture of Hasidic life and an analysis of texts which comes across as more objective and thus can actually be more inspiring as well.

In this context, I wish to close with a short story that no doubt would have left Scholem bemused and perhaps even perplexed.11 One of my former congregants, today a strictly Orthodox and neo-Hasidic grandmother who grew up in a completely secular home in Canada, told me the following when I asked her how she was first attracted to Judaism. She explained that quite by accident she came across a copy of Major Trends, which changed her life. Up until then she had been convinced that spirituality, and certainly mysticism, was only to be found in Eastern religions. The book opened her eyes to the fact that Judaism as well had a very rich mystical tradition. And with that she began her long journey home. I suspect that many others, like myself, were first exposed to “Jewish Mysticism” reading Scholem in university, and that played a significant role in their interest in important aspects of the Judaic tradition that we hadn’t been exposed to in Hebrew School. Therefore, while his influence on Orthodox neo-Hasidism may have been circuitous, Scholem has no doubt played a role in this movement as well. He, more than anyone else, is responsible for bringing Kabbalah out into the open and mainstreaming it in Judaism beyond the small, Kabbalistic elite.

In conclusion, I would like to add that many of Scholem’s correspondents and those who wrote dedications in the volumes they presented to him, were careful to refer to him as “R.” or “Reb” Gershom. One of them was the scholar of Hebrew literature, Prof. Dov Sadan, who also quipped that in the verse in Psalms (55:15), “in the house of God we would walk with a multitude (ברגש, which can also be interpreted as “with emotion), the word ברגש can be read as an acronym בספריית ר’ גרשם שלום – in the library of Reb Gershom Scholem!

Rabbi Dr. Zvi Leshem directs the Gershom Scholem Collection for Kabbalah and Hasidism at the National Library of Israel in Jerusalem. He is a contributor to the Encyclopedia Hebraica, second edition.

[Originally published January 21, 2021]

- The book was first published in German in 1977, when Scholem was eighty years old. Yet the biography only covers his early life, ending in 1925 when he was a mere 28!

- Some notable titles in English, since 2017 alone, include: Amir Engel, Gershom Scholem: An Intellectual Biography; George Prochnik, Stranger in a Strange Land: Searching for Gershom Scholem and Jerusalem; David Biale, Gershom Scholem: Master of the Kabbalah; Mirjam Zadoff, Werner Scholem: A German Life; Noam Zadoff, Gershom Scholem: From Berlin to Jerusalem and Back; Jay Howard Geller, The Scholems: A Story of the German-Jewish Bourgeoisie from Emancipation to Destruction; and Mirjam Zadoff and Noam Zadoff, editors, Scholar and Kabbalist: The Life and Work of Gershom Scholem.

- See Steven M. Wasserstrom, Religion After Religion: Gershom Scholem, Mircea Eliade, and Henry Corbin at Eranos (Princeton University Press, 1999).

- Berel Wein, Triumph of Survival: The Story of the Jews in the Modern Era 1650-1990 (Mesorah, 1990), is a good example:“Scholem, generally, is very biased against rabbis and traditional Judaism, and this colors his scholarship” (24 n. 6); see also: “The acute bias against all traditional rabbis and rabbinic thought of such secular Jewish scholars as Graetz, and in modern times, Gershon [sic] Scholem, shows through in their strident accusations that Rabbi Yonasan [Eibeshutz] was a secret follower of Shabtai Tzvi, even though all available evidence is to the contrary” (34 n. 9). R. Wein’s characterization of Graetz as “secular” also seems open to question. See as well the recently published anthology, Torah & Rationalism: Writings of the Gaon Rabbenu Aaron Chaim HaLevi Zimmerman zt”l, Moshe Avraham Landy, ed. (Feldhaim, 2020), Where Scholem cannot even be mentioned by name, instead is referred to as ““this secular writer.”

- Scholem’s student Isaiah Tishby said the following on this point: “My yeshiva background definitely helped me in my later scholarly research… I believe a researcher should be both inside and outside his subject. One should have empathy with those whose works one studies. To identify with the world of the Kabbalists, to know their thinking… A researcher resembles an actor…to enter the personality he is portraying. To a certain extent, so must the researcher.” “Tishby – My Early Years” in “Kabbalah: A Newsletter of Current Research in Jewish Mysticism” 1:3 (Spring 1986).

- For example R. Menachem Mendel Kasher in his article “Zohar,” Sinai (1958), 40-56.

- The prominent social and literary critic Baruch Kurzweil devotes an entire chapter to attacking Scholem’s book on Shabbtai Zvi, accusing him not only of a lack of objectivity, but going so far as to equate his research with nihilism and demonology! (See two chapters in Kurzweil’s 1969 book BeMa’avak al Erkhei ha-Yahadut.) More recently see David Biale, Gershom Scholem: Master of the Kabbalah (Yale University Press, 2018): “beneath his damning words about Frank lies an inescapable fascination, as if Frank personified his own demons” (129).

- On this entire bizarre incident see my article “On Gershom Scholem, Conspiracy Theories and Rabbinical Court Controversies,” The Librarians Blog (NLI).

- The one exception may be his view that Hasidism served to neutralize the messianic impulse in Judaism, which had gone awry in Sabbatianism. See Scholem, The Messianic Idea in Judaism and other Essays(Schocken, 1971), 176-202.

- See Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism, 332: “The greatest and most impressive figure of classical Zaddikism, Israel of Rishin…is, to put in bluntly, nothing but another Jacob Frank who has achieved the miracle of remaining an orthodox Jew.” According to rumor, Heschel pleaded in vain with Scholem to remove this vicious attack on his ancestor. This may also help to explain his rather tepid review of Major Trends, in The Journal of Religion (April 1944), 140-141. Paradoxically, Heschel’s association with JTS makes him suspect to some in the Orthodox community, despite his traditionalism, whereas Scholem, perceived as being “secular” and therefore spiritually “parve” may be more acceptable.

- In February 1980 I was present when Scholem addressed a group of religious university students in Jerusalem. He was astounded by the very large turnout. (Recording of that event available here.)