REVIEW: Studies in Halakhah and Rabbinic History

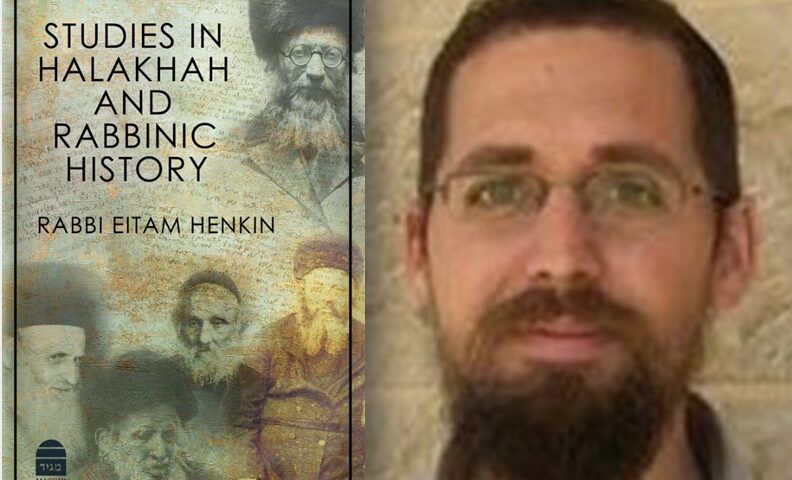

Eitam Henkin, Studies in Halakhah and Rabbinic History, edited by Chana Henkin in collaboration with Eliezer Brodt (Maggid Books), 456 pages

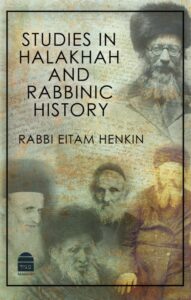

The Talmud recounts “the Holy One, blessed be He, said to Moses: Woe over those who are gone and are no longer found” (Sanhedrin 111a). The phrase came to mind when I sat to write this encomium for R. Eitam Henkin, in recalling that he and his wife Na’ama הי”ד were murdered on Sukkot in 2015. As God Himself mourns irreparable losses, all readers of R. Henkin’s Studies in Halakhah and Rabbinic History will do the same.

The Talmud recounts “the Holy One, blessed be He, said to Moses: Woe over those who are gone and are no longer found” (Sanhedrin 111a). The phrase came to mind when I sat to write this encomium for R. Eitam Henkin, in recalling that he and his wife Na’ama הי”ד were murdered on Sukkot in 2015. As God Himself mourns irreparable losses, all readers of R. Henkin’s Studies in Halakhah and Rabbinic History will do the same.

From the evidence offered in his writings—his excellent and educational previous book on Arukh HaShulhan and this current collection of articles—the loss of this young talmid hakham is compounded by the promise of future scholarship of which we will be deprived. Ta’arokh Lefanai Shulhan, articles and studies on the life and works of R. Yechiel Michel Epstein, was clear, informative, well-researched, and well-written.

Studies in Halakhah and Rabbinic History demonstrates other valuable sides of R. Henkin’s oeuvre. The book has three parts: First, halakhic studies, some of them arguing for a leniency others had dismissed. For example, based on the research of those who required three washings to remove all the insects on strawberries and the like, he shows that the first washing reduces their number below the threshold needed to ignore their possible presence. Similarly, in another article he justifies the practice of waiting just over five hours between meat and milk, not needing the full six.

Lest we think he simply always found the easier path, his discussion of electric eyes/keycards on Shabbat objects to a leniency suggested by others, arguing that those actions count as the person’s on Shabbat, and are therefore prohibited. We would need more evidence to be sure, but he seems concerned with the truth, sometimes more lenient than the consensus, sometimes more stringent, not with landing on either particular side of the line.

The second section, the bulk of the book, presents studies in rabbinic history, befitting a young scholar who was still working toward his doctorate. The range is impressive, a few from the time of the Talmud, one from the medieval period, the majority focused on the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, his clearly preferred period (as his earlier book showed).

I particularly enjoyed the six chapters (of sixteen) touching on Rav Kook. It begins with Arukh HaShulhan’s ordination of R. Kook (combining two of his interests); three chapters on R. Kook himself—his attitude towards Keren HaYesod; an investigation of two versions of R. Hutner’s report of R. Kook’s feelings regarding Hebrew University’s eventual inclusion of Biblical Criticism in its curriculum); and whether R. Kook softened his view of Eliezer Ben-Yehuda upon the latter’s death. The section concludes with two fascinating analyses of cases where Haredi children or grandchildren of those close to R. Kook tried to remove that perceived “stain” from their ancestor’s biographies, and even from their writings (identifying the central culprits along the way).

Throughout these sections—three-quarters of the book—R. Henkin shows two traits I note with admiration: first, his passion for truth, particularly when someone else has gotten that truth wrong. Many essays respond to or rebut a position someone else has taken, he believes, in error. He disputes those stances with care and respect, even as his burning interest in recovering the truth of the matter comes through. It is not personal, although it can be passionate, nor does it give the sense of someone interested in winning a debate; it feels, simply, like his visceral reaction to something untrue being placed in the public domain. When he shows that R. Elchonon Wasserman erred in attacking R. Kook for his support of Keren HaYesod, he demonstrates why R. Wasserman would have had ample reason for his mistaken view. When he clarifies an interaction between R. Kook and R. Hutner regarding Hebrew University, when he gets to the truth of R. Kook’s view of Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, the tone can be strident, impatient with those who presented untruths or half-truths, but he only criticizes when he has reason to believe people were deliberate in their lies or misrepresentations, such as the Haredi descendants who expurgated their ancestors’ writings to cleanse them of admiration for R. Kook and/or the yeshiva he founded.

Henkin seems to have had boundless energy for the research needed, his citations documenting his moves among many types of literatures and sources in pursuit of what he sought. Because of that, incidentally, many of these studies can only really be appreciated with a step I did not take, checking the footnotes, seeing how those who came before him read them, what he added to the conversation, how he furthered our understanding of the issue.

The last quarter of the book presents two pieces about his great-grandfather, R. Yosef Eliyahu Henkin zt”l, welcome if only because—as he notes—the memory of the man has been somewhat lost, perhaps because the elder R. Henkin devoted 48 selfless years to Ezras Torah, a charity organization, putting his roles as posek and author on the back-burner, his job leaving him only three hours a day to study Torah. As the younger R. Henkin, notes, when his great-grandfather did write he put his major essays in the annual publication of Ezras Torah, to help the organization raise its much-needed funds.

I learned much about the elder R. Henkin that I enjoyed, especially regarding his interactions with Hazon Ish and R. Moshe Feinstein. I had often wondered what it would be like to be the premier posek in America, and then have R. Feinstein, fourteen years younger, a later arriving neighbor on the Lower East Side, eventually (it always seemed to me) eclipsed his elder, both in the public eye and in halakhic weight. R. Eitam Henkin’s reports of their friendship and mutual admiration relieved me of any worries about jealousy or other lesser character traits.

The last chapter brings together historical and familial interests, re-examining the elder R. Henkin’s role in the Langer Affair, an issue that roiled the State of Israel of the late 1960s and early 1970s. In brief, the siblings Hanoch and Miriam Langer, born in the mid-1940s, had been declared mamzerim by a succession of rabbinic courts. After R. Shlomo Goren became Chief Rabbi, he overturned the previous rulings and allowed them to marry as they wished.

There were castigations from the religious right, for whom this was a reason to cease cooperation with the Chief Rabbinate, and proof of the institution’s essential corruption; it was the reason R. Elyashiv stepped down from his position on a governmental rabbinic court. The Religious Zionist community rushed to R. Goren’s defense, and both sides claimed the support of the aged and no-longer-sighted R. Yosef Eliyahu Henkin. His great-grandson tracks down a crucial new source, from his grandfather’s notes of a visit to the elder R. Henkin, to shed light on the issue, to explain how both sides came to believe what they did, and what he understands R. Henkin’s actual position to have been, that while he could not comment on the issue itself, being too frail to delve into it, he trusted R. Goren as a Torah scholar, and expressed that support.

Precisely because great talent is rare, the tragedy of its loss reverberates, not least for the family. Those who brought this book to light have performed multiple services, bringing a touch of comfort to the family, leaving his sons, who thank God survived, with another way to develop and maintain contact with their father, taken from them before they had the chance to know him as children deserve, and giving all of us some access to what this creative and assiduous mind had been doing with his time.

Reading this fine book, each specific essay as well as the overall experience of meeting this writer, will reward the reader. We owe all involved great thanks for giving us, and the family, this wonderful monument to its author’s memory. May his lips move in the grave as people read and learn from him, increasing his legacy in this world beyond the remarkable one it had already been.

Rabbi Gidon Rothstein teaches at WebYeshiva.org, blogs at TorahMusings.com, and writes Jewishly-themed fiction and non-fiction, most recently Judaism of the Poskim: Responsa and the Nature of Orthodox Judaism.