Temporality and Freedom

Before the TRADITION editorial headquarters shuts down for the Sukkot holiday we bring you another dispatch from Avraham Stav with his insights on the balance between the front and the home front….

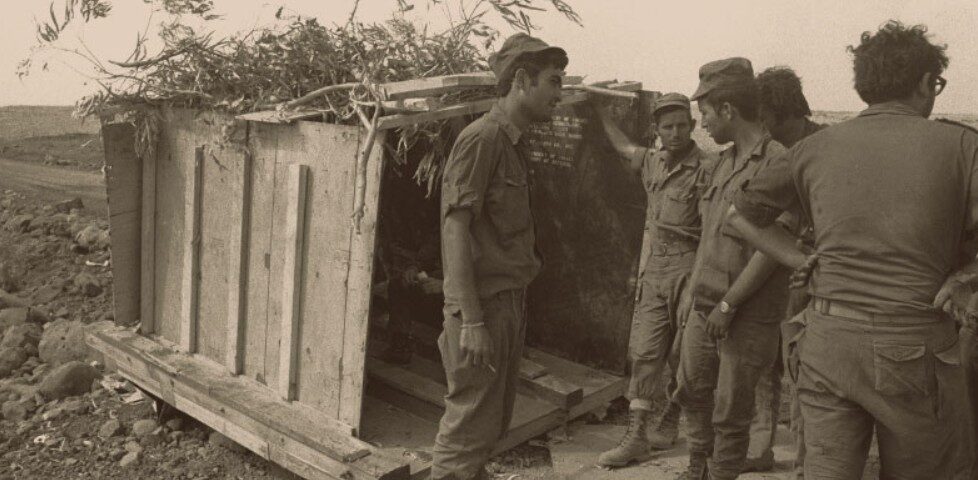

An impromptu Army sukka, Yom Kippur War 1973 (photo: IDF Archive)

On the first night of the war, two years ago, I didn’t sleep, of course. Almost no soldier slept then. Maybe I just laid my head for an hour or so on a duffle-bag in the unit’s warehouse. On the second and third nights, I was already settled in with an army-issued sleeping bag on the side of our armored personnel carrier. On the fourth day, the donations started to arrive. At first, thin yoga mats (one of which is still used by my teenager). Then, field cots that we slept on in rotation. After a week or two, small camping tents began to arrive. At first, three or four of us shared a tent. Later, we became a little more comfortable. And about a month after the war began, each soldier already had his own tent, and a personal cardboard bed that gradually absorbed the shape of his body. We also improved our trenches with each move. In the third area where we deployed, we had already built an improvised mud oven, and in the fourth, we built a fully equipped wooden kitchen from artillery debris.

I remember the first time in the war that I set foot inside an actual outpost. I had just returned from a short break at home, and I had brought my sleeping bag and personal tent to the location I had been instructed to reach. But the battery commander pointed to a white metal structure: Here, you sleep here. I looked at the bare iron bed (there was only free space left on the top bunk), and had difficulty accepting the fact that for the next two months this was going to be my home. I walked by the barbed wire fences that were stretched around the buildings, glanced at the battalion dining room, with its proper finished floor, and found myself longing for the cardboard bed in the dugout, which was so obviously not meant to house anyone for a sustained period of time.

One of the most beautiful halakhot is the one that requires starting to build the sukka as soon as Yom Kippur is over. Going from one mitzva to another. Capturing the spirit and fixing it with nails. Building houses for dreams. Giving the spiritual a physical form. Not being satisfied with a general promise that we will be better, but showing how we are implementing it with facts on the ground.

The power of the sukka comes from the knowledge that in a week you will dismantle it. After all, the part that scares us the most about change, personal or communal, is permanence. The reluctance to bind ourselves with commitments that we don’t know if we’ll keep or if we’ll even want to. That’s why it’s so important to know that Sukkot is seven days and done. It’s a dramatic promise from all sides: It’s only going to be for a week. There are no long-term commitments. The subscription is not automatically renewed. On the contrary, even if you want to stay in the sukka after the holiday, we’ll force you to leave. And now, with this knowledge, what would you like this week to look like?

It turns out that it’s precisely the knowledge that it’s temporary that grants us the freedom—to decorate the walls with bombastic, childish decorations, to invite guests from all directions—because it’s clear to that they won’t be around in seven days.

Israeli society lives with a lot of fear. We’re afraid that we’ll turn into Sparta or Manhattan or Iran. We look at demographic tables, at in-depth surveys, at social trends, and we’re afraid that in the house that’s going to be built here, there won’t be room for us. Because the left will come to power, because the Haredim will be the majority, because the right is getting more radical, because the progressives are getting more crazy. And that makes us close the doors and fortify the walls, and make sure that our specific way of life will somehow manage to survive.

But what if they had told us that all of this was only for a week, or a month, or a year? I think that was the force that united us at the beginning of the war. Not only the sense of distress and emergency, but also the sense of transience. The understanding that this was an exceptional, momentary situation, without obligations. So we looked left and right, we saw the Hardali “hill boy” from Samaria and the secular representative of “Brothers in Arms” and said, “Yalla, right now, just as you are, I want to go into battle with you. Then we’ll see what happens.”

The original Sukkots, as it is stated in the books of Samuel and Kings, were used many times during warfare. It is as if the Torah seeks to return us to the temporary structures in which we lay together when we went into battle. To the scout tents where we were crammed together without distinction. Because who cares, a few days and it’s over. And it was precisely from this knowledge that the most unexpected connections, the most beautiful friendships, could be formed. After the holiday, we will worry once again about the future. But a year must begin from a fantasy. A nation must be born from a dream.

Rabbi Avraham Stav teaches at Kollel Shaarei Zion in Yad HaRav Nissim, Jerusalem, when he is not serving in an artillery unit.