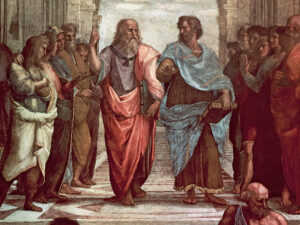

The BEST: Dialogues of Plato

Summary: Plato (428 – 347 BCE) and his teacher, Socrates, were among the ancient Athenian philosophers considered to be founders of Western thought. While Socrates did not leave any written record, Plato ascribed a great many ideas to him through his own writings, most notably in the form of dialogues between Socrates and others.

Socrates was known for affecting lack of knowledge. In fact, the awareness of this lack was the sole piece of wisdom he would claim. As portrayed in the dialogues, Socrates used the premise of his own ignorance to draw others, who thought themselves wise, into conversation; these discussions generally amounted to a series of seemingly simple questions through which Socrates would gently highlight flaws in others’ logic and leave them less sure of themselves than they had been. It is perhaps not surprising that he was considered a threat to ancient Greek society and sentenced to death – but his ideas and methods have survived and thrived.

In Plato’s dialogues, Socrates and his company dispute metaphysics as well as human and political virtue. They argue over religion and science, human nature, love, and sexuality. These dialogues contrast perception and reality, nature and custom, and body and soul. They form a philosophy for how one can understand one’s place in the world and live an intelligent and happy life.

Why this is The BEST: Socratic dialogue has echoes in Jewish tradition – a tradition, of course, that includes not just the dialogues found in Tanakh (beginning all the way at the beginning; e.g., Gen. 1:26, 3:1, 9, 11), but those that have made up the core of the Oral Law and halakhic discussions for thousands of years. We would do well to study and appreciate it as such. The centrality of questions has made its way into modern Jewish culture as well, at the root of jokes about how Jews answer questions with questions. We think in questions; we dig into our texts and find ourselves full of questions. Our never-ending questions keep our oral and written traditions alive and relevant.

Why this is The BEST: Socratic dialogue has echoes in Jewish tradition – a tradition, of course, that includes not just the dialogues found in Tanakh (beginning all the way at the beginning; e.g., Gen. 1:26, 3:1, 9, 11), but those that have made up the core of the Oral Law and halakhic discussions for thousands of years. We would do well to study and appreciate it as such. The centrality of questions has made its way into modern Jewish culture as well, at the root of jokes about how Jews answer questions with questions. We think in questions; we dig into our texts and find ourselves full of questions. Our never-ending questions keep our oral and written traditions alive and relevant.

As a teacher, I question my students, and I want them to question me – because, like Socrates says, wisdom is knowing the limits of our wisdom; asking and answering questions helps us identify those limits and expand our thinking past them. The question approach highlights absurdities and contradictions as well as more nuanced flaws in logic.

In the “Euthyphro” dialogue, for instance, Socrates highlights the absurdity of claiming piety is defined by what the gods approve when one believes in multiple gods who are forever in conflict and disagreement. By asking questions as if in a sincere desire to learn from someone wiser than he, Socrates forces Euthyphro to realize the corner he’s backed himself into. While many discussions in the Dialogues are much more complex, this one stands as an example of how a series of fairly simple questions can lead to serious thought and rethought – one that my 11-year-old was able to follow when I surreptitiously left “Euthyphro” open for him to find.

“Euthyphro” stands out, from the perspective of a monotheist, for its content as well. Though polytheism is not today the established social force that Socrates had to contend with, philosophical analysis, of what we believe and why, is always relevant. I was pleased to see my son discover Euthyphro for that, as an introduction to thinking more deeply about the basic theology with which he’s being raised. I may not have been concerned that the fantasy books he loves would lead him to polytheistic beliefs, but I am still glad for him to begin to learn why not – and as he gets older, to begin to appreciate other philosophical questions and analyses, digging deeper into what people have believed over centuries of human thought and to what extent various concepts are and are not reflected in our own tradition. That process involves a great many sources and thinkers across philosophical history, but it begins with the ancients like Socrates and Plato.

As it happens, my own introduction to the Dialogues came at my son’s age or younger, and contributed to my developing love for analytical thought and learning. With a father who was a philosophy professor, it is perhaps not a surprise that I was introduced to Plato early on – though my father gave me the Dialogues one night not to teach me, but to bore me and help me fall asleep. It didn’t work; I was pulled in. Experiences like that introduction to Plato and his teacher’s questions and attempted answers, from the relatively simple to the more complex, played a huge role in catalyzing my love of Jewish learning, which I experience and revel in as one giant sparkling web of questions and answers.

Sarah Rudolph, an editorial board member of TRADITION, is a freelance Jewish educator and writer in Cleveland, editor-at-large for Deracheha, and director of TorahTutors.org. Click here to read about “The BEST” and to see the index of all columns in this series.