TRADITION QUESTIONS: The Orthodox Omnivore

Click here to read about this series.

What’s happening?

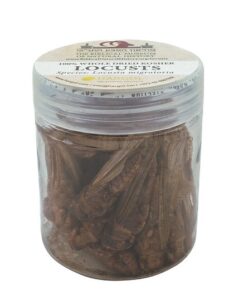

In early 2021, The Biblical Museum of Natural History began offering for sale (online and at the museum) small plastic jars containing approximately 20 migratory locusts (locusta migratoria). Advertised as “100% whole dried kosher locusts,” the critters were raised for human consumption (to be eaten as a protein powder) by Hargol FoodTech, an Israeli startup. While they may be the most popular item in the museum gift shop (as reported by the museum in April 2022), these newly available delicacies have not become popular on wedding menus or Shabbat tables.

Rabbi Natan Slifkin, the museum director and self-styled “zoo rabbi,” makes a compelling argument for the permissibility of these insects: “It is legitimate to rely on those who do have a tradition, just as we are allowed to accept traditions from communities regarding the kosher status of various birds, provided that we have no tradition against them.” (For more on the history, halakha, and sociology—and the museum’s rationale for advocating the eating hagavim—see Slifkin’s article.)

Rabbi Natan Slifkin, the museum director and self-styled “zoo rabbi,” makes a compelling argument for the permissibility of these insects: “It is legitimate to rely on those who do have a tradition, just as we are allowed to accept traditions from communities regarding the kosher status of various birds, provided that we have no tradition against them.” (For more on the history, halakha, and sociology—and the museum’s rationale for advocating the eating hagavim—see Slifkin’s article.)

No public outcry against the museum for selling locusts has materialized. Yet, locusts have not “caught on” within the Orthodox community in Israel or the diaspora. Why?

Why does it matter?

We might assume that the failure of the kosher food market to adopt the locust relates to controversy surrounding Jewish law. Yet, if that were the case, we would expect those in the Jewish community who do accept its permissibility to both consume locusts and to promote its consumption. Yet, that does not seem to be happening.

Halakha asks whether something is mutar or asur (permitted or forbidden). It rarely asks if it is worth eating. The viability of “new” kosher foods creates an “Omnivore’s Dilemma” for the kosher consumer. In his 2006 book, Michael Pollan describes humans as having a variety of food choices. He suggests that, prior to modern food preservation and transportation technologies, the dilemmas caused by these options were resolved primarily by cultural influences. In the case of the kosher consumer, these were and are also limited by halakha. Technology has made foods that were previously seasonal or regional available year-round and around the globe. Pollan argues that the relationship between food and society, once moderated by culture, is now confused. The locust question touches on many of these themes. Foods that were once limited to the Yemenite Jewish community are now available to everyone. The potential to look beyond agribusiness to a niche organic product also beckons.

On the surface, such new optionality appears like a good thing. Who doesn’t like choice? The Talmud writes: “Are these matters not inferred a fortiori? And if this nazirite, who distressed himself by abstaining only from wine, is nevertheless called a sinner and requires atonement, then with regard to one who distresses himself by abstaining from each and every matter of food and drink when he fasts, all the more so should he be considered a sinner” (Taanit 11a).

To abstain from a food that the Torah permits might likewise be understood on some level to be a sin. This supports “foodie” culture’s impulse to explore strange new delicacies. Yet, having a choice means that we will choose. Locusts were a food that was eaten when there was no choice. After a locust swarm devoured all the crops, the human population was required to consume those locusts in order to survive. In his Melekhet HaKodesh (Shemini 11:21), Rabbi Moshe Toledano (1724-1773) makes this argument: “The law is that these locusts that come during a terrible time for Jacob and destroy all the crops … that it is permissible to eat them.” In other words, the Torah allows eating locusts in order to sustain a plague-ridden famine society at need—not as some haute cuisine delicacy to be partaken of as some kind of item on a gastro-tourism bucket list.

In this regard, it is worthwhile to consider the choices of those not constrained by Jewish law. Whole Foods does not have a locust section. People who “pop” the locust jar are more than able to “stop” eating them. People choose to eat bread and meat – they do not choose to eat locusts when they have a choice.

What questions remain?

The Kosher eater has always been a part of two culinary cultures: The particular Jewish culture molded by internal demands of halakha and Jewish lifestyle and the wider food culture beyond the shtetl’s gates. Today’s food culture has witnessed tremendous transformations that the Orthodox community has largely adopted unquestioningly. The kosher consumer enjoys kiwi fruit and corn syrup-based soft drinks. Perhaps, we should ask questions. What elements of our Orthodox omnivore’s dilemma – in terms of consciously choosing our foods – might allow for better Jewish culinary and social outcomes on an individual and communal level?

Does the culture of curiosity (which is severely limited by halakha) manifest itself in problematic ways when it comes to conspicuous consumption of the permitted (see Ramban to Vayikra 19:2)?

Chaim Strauchler, an associate editor of TRADITION, is rabbi of Cong. Rinat Yisrael in Teaneck.