Unpacking the Iggerot: Kippa on the Job

Read more about “Unpacking the Iggerot” and see the archive of all past columns.

Read more about “Unpacking the Iggerot” and see the archive of all past columns.

Can I Keep-ah My Job? Iggerot Moshe, Orah Hayyim, vol. 4, #2

Summarizing the Iggerot

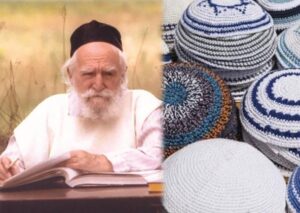

In addition to the pure halakhic content they provide, the Iggerot Moshe, R. Moshe Feinstein’s responsa, serve as a window into the struggles of American Jewry during the mid-late 20th century. R. Feinstein witnessed many Jews who were faced with an ultimatum in which they were forced to decide between commitment to Sabbath observance and putting bread on their families’ tables. A related conflict of values was presented to him in 1974 by a Mr. Hillel Erlanger, who was advised that if he were to wear his yarmulke he would be denied a job he had applied for. R. Moshe was asked for his guidance on how to navigate the competing necessities of wearing a kippa with the essential need to earn a living.

Despite the fact that early sources indicate that a head-covering inspires reverence for Heaven (Shabbat 156b), R. Feinstein infers that it is only a middat hassidut, a pious practice, rather than a formally mandated Biblical or even Rabbinical obligation. He further cites the ruling that one is not required to forfeit more than a fifth of his assets to perform a positive Biblical commandment (see Rema, O.H. 656:1) and argues that if one is not expected to sacrifice all of his monetary holdings for a bona fide Biblical commandment, it certainly stands to reason that one should not be required to do so in order to observe what is “only” a pious practice.

In the second section of the responsum, R. Feinstein cites the Taz (O.H. 8:3) who adds an additional rationale for requiring Jewish men to wear a head-covering. Since it was the practice of Christians to remove their head-coverings for religious worship, Jews should specifically maintain their head-coverings so as not to emulate non-Jewish customs. R. Feinstein suggests that given the fact that most gentiles today generally keep their heads uncovered out of mere convenience, in extenuating circumstances such as this, there would be no fundamental concern of possibly emulating non-Jewish practices. Thus, R. Feinstein ruled that such an individual may remove his kippa if that was the only thing standing between him and earning a living.

Connecting the Iggerot

But we must not think that R. Moshe Feinstein’s ruling was meant as a carte blanche permission slip. In another responsum (Iggerot Moshe, Y.D., vol. 4, #11:3) he advises wearing a hat when a kippa is not viable. Moreover, he writes (Iggerot Moshe, H.M., vol. 1, #93) that even should one need to remove his kippa for work he should be conscientious about wearing it when going out for a lunch break or a similar setting where it will not conflict with his employment status.

In a rather amusing responsum (Iggerot Moshe, O.H., vol. 2, #95), he was asked whether someone who “succumbs to his evil inclination” and goes to a movie theater should remove his kippa. R. Feinstein rejects such a rationale:

Since it is farfetched to suggest that such a man who succumbs to his lust is intending for the sake of Heaven, his intent is only to degrade himself further through the violation of uncovering his head—thus he should not be permitted to [remove his kippa].

Despite, R. Feinstein’s willingness to issue a dispensation to go bareheaded for employment purposes, it is clear that he sought to localize it as a very narrow dispensation. Nonetheless, it is noteworthy to see how R. Feinstein, who clearly placed a premium on wearing a kippa, was willing to balance it with the pragmatic considerations of attaining employment.

Challenges to the Iggerot

However, for some of his contemporaries, R. Feinstein did not go far enough. On a technical level, Sefer Kevod Melakhim (Halakha le-Moshe me-Sinai, no. 3, Laws of Expending One’s Finances, no. 10) cited in the comprehensive, two-volume Otzar HaKippa, weighing in at over 1,500 pages (vol. 1, pp. 401-402), questions R. Feinstein’s extrapolation from the principle of not spending more than a fifth on a mitzva to our scenario. While in the case of the Gemara and Rema one is actively sacrificing his finances, turning down a job is only forgoing a future earning opportunity.

On a more fundamental level, R. Moshe Stern (Responsa Be’er Moshe 8:40) advances fierce rhetoric to impress upon us the critical importance of wearing a kippa. He quotes Hatam Sofer who reportedly remarked, “A man who uncovers his head is a sheigetz, and because he is a sheigetz he uncovers his head.”

Moreover, he relates that a couple “from the group of reformers who keep Shabbat and taharat ha-mishpaha, but otherwise live like typical Americans” came before him to air their grievances against each other. In an attempt to undermine her husband’s credibility, the wife claimed that the husband is not religiously trustworthy because he removes his kippa when he sits down to read the newspaper in the evening. The husband reflected upon this and admitted that perhaps it was his lack of diligence in covering his head that led them to their sorry marital state. The wife accepted this remorse, they reconciled and went on their merry way. R. Stern concludes from this incident: “Even among the ‘modernizers,’ uncovering their head is considered a severe sin and one [who neglects to cover his head] is called a transgressor.”

After marshaling several other arguments, R. Stern concludes—against R. Moshe’s opinion— that the inquirer should decline to take the job if it means compromising on wearing a kippa. As these stories tend to go, this individual found another job shortly thereafter that enabled him to wear his kippa—and it was even financially better than the original option!

Reflecting on the Iggerot

From a methodological standpoint, it is noteworthy to observe how R. Feinstein limited his responsum to halakhic formalism. Unlike R. Stern who made an identity-based argument for the indispensable imperative to wear a kippa, R. Feinstein took a more pragmatic approach in which he weighed the limited halakhic gravity of a kippa versus the extenuating circumstances of attaining employment. Perhaps, we can conjecture that from R. Feinstein’s standpoint, if an observant Jew could be fortunate enough to find employment that would allow him to take off on Shabbat, he saw it as a battle already won, and was not willing to make a kippa, despite its special significance, the halakhic hill to die on.

Feinstein, in his role as a guide for American Jews, understood that he bore the responsibility to look after not only the considerations of the individual before him but the continuity of the Jewish people as a whole. My Rebbe, R. Dr. Moshe D. Tendler zt”l (son-in-law of R. Feinstein), would frequently point out unspoken factors in R. Feinstein’s halakhic arithmetic that did not make it onto the pages of the Iggerot Moshe. It would not surprise me if R. Feinstein also took into account the broader needs of the community when rendering a more lenient position on this issue. (Unlike in the case of working on Shabbat for which he brooked no leniency.)

As we continue to unpack the Iggerot Moshe, it will be interesting to consider when and why R. Feinstein opted to take a more passionate and vehement approach to some issues while adopting a more flexible and pragmatic position on other pressing matters. In the samplings we will be offering in this series, it is my hope that we can develop a profound appreciation for the posek ha-dor, HaGaon Rav Moshe Feinstein zt”l.

Endnote: In regards to whether a non-Jew working in a Jewish environment should wear a kippa, see R. Yonasan Rosman’s Petichat HaIggerot (p. 230). For a comprehensive resource on the broader topic surveyed here, see Otzar HaKippa (Gate 4, ch. 1). Recall that the very first responsum published in Iggerot Moshe deals with the size of a kippa (O.H. vol. 1, #1).

Prepare for the next column (appearing April 18) on Breakaway Minyanim and Hasagat Gevul / Iggerot Moshe, H.M., vol. 1, #38.

Moshe Kurtz serves as the Assistant Rabbi of Agudath Sholom in Stamford, CT, is the author of Challenging Assumptions, and hosts the Shu”T First, Ask Questions Later podcast.