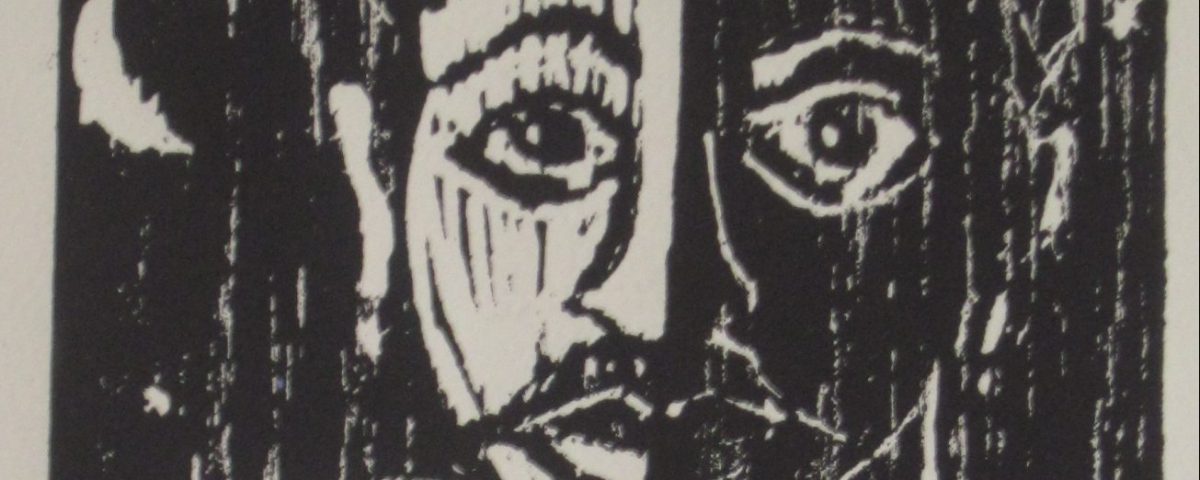

WOODCUT MIDRASH: Laban – The White Liar

And it came to pass, when Laban heard the tidings of Jacob, his sister’s son, that he ran to meet him, and embraced him, and kissed him, and brought him to his house. And he told Laban all these things. And Laban said to him, Surely you are my bone and my flesh. And he abode with him for a month. Laban said to Jacob, Because you are my brother, should you therefore serve me for nought? Tell me, what shall your wages be? Laban had two daughters: the name of the elder was Leah, and the name of the younger Rachel. Leah was tender eyed; but Rachel was beautiful and well favored. Jacob loved Rachel; and said, I will serve you seven years for Rachel your younger daughter. Laban said, It is better that I give her to you, than I should give her to another man: abide with me. So Jacob served seven years for Rachel; and they seemed unto him but a few days, for the love he had to her. Then Jacob said to Laban, Give me my wife, for my days are fulfilled, that I may go in unto her. Laban gathered together all the men of the place, and made a feast. In the evening, he took Leah his daughter, and brought her to him; and he went in to her. Laban gave to his daughter Leah Zilpah his maid for a handmaid. And in the morning, behold, it was Leah: and he said to Laban, What is this you have done to me? Did not I serve you for Rachel? Wherefore then have you beguiled me? Laban said, It must not be so done in our country, to give the younger before the firstborn. Fulfill her week, and we will give you this also for the service which you shall serve with me yet seven other years. Jacob did so, and fulfilled her week: and he gave him Rachel his daughter to wife also. And Laban gave to Rachel his daughter Bilhah his handmaid to be her maid (Genesis 29:13-30).

Laban the Aramean is a son of Bethuel and grandson of Nahor, the brother of Abraham. These progeny are mentioned in the chronology at the end of the Akeda (Genesis 22), climaxing in the note that Bethuel also gave birth to Rebecca (22:23), and thus prepared a wife for Isaac. Laban’s name is, however, conspicuous by its absence. To compensate for this the sages suggest that Kemuel – who is mentioned as one of Milcah’s eight children – is actually Laban. In a typical piece of rabbinic word play his name is interpreted as “he rose up (kamu) against the people of God (el)” (Breshit Rabba 57:4).

These uncertain beginnings already cast a shadow over this most murky of characters. On the one hand he his born into a family of renown. Midrash

HaGadol links his birth with that of Isaac’s – in that, like Sarah, Milcah is barren and only the merit of Sarah’s miraculous pregnancy causes her to become pregnant. He is, moreover, the father of two righteous daughters, Leah and Rachel. On the other hand, his name is forever associated with mean-hardheartedness, miserliness, and skullduggery.

Perhaps the reliance on the supernatural at his very birth indicates the potential path that Laban is to take. Indeed if the Sages are correct about his original name – then the name Laban may have been one that he deliberately chose for himself to give the false impression of his honesty. He could find a name no more fitting, if not indeed more Machiavellian. Though this name means white – the behavior with which he is most identified is of the darkest hue. It is, moreover, the peculiar blackness with which the wicked are often capable of – disguising their evil in a cover of righteousness and legality. When he first meets Jacob and sees an opportunity of exploiting him, he pointedly tells him that unlike the custom back in Canaan, in Aram they marry off the eldest first and only after that the youngest. Since Jacob wishes to marry the younger of Laban’s two daughters, Rachel, he feels entitled to deceive him. Ironically he plays here the part of a judge – paying Jacob back for his own deception of his father Isaac and his hateful brother Esau (29:26).

Interestingly, the mystics see Jacob’s own character traits as being in part to blame for his being exploited. When Laban asks his local idolatrous oracle what wages he should pay this stranger, they tell him not to pay him since Jacob is a lover of women his brides will serve as his wages. The oracle, moreover, advises Laban that “every time Jacob appears to want to leave you – just offer him another wife” Thus Jacob takes upon himself not just the two sisters, but also the two concubines, Zilpah and Bilhah. This is in stark contrast to his own family where Isaac and Rebecca remained totally monogamous. Despite the fact that he is head over heels in love with Rachel, for whom he works for seven additional years, he is not averse to accepting other women into his household.

Laban’s trickery is also apparently connected to his birth place and background in Aram which the Sages connect to the Hebrew word ramay, a liar and a cheat (Bereshit Rabba 70:19). Not only does he cheat this stranger from the West, he also cheats his own people (ibid.). Thus it is no surprise that the Sages link his genealogy with another famous warlock from Aram – namely Balaam (Sanhedrin 105a). Thus, too, though Laban disappears from the narrative, after he turns aside from pursuing Jacob, he “appears” under a suitable disguise some generations later – to cast his supernatural powers over the Children of Israel – in roughly the same way. First he seems to bless them (Laban’s last act towards Jacob and his family) and, when this fails, to hedonistically lure the Israelite men with the daughters of Moab resulting in the deaths of 24,000 Israelite men (Numbers 25:1-9).

This reference to a later generation might be a way for the Sages to understand Laban’s fate. Despite the fact that he is clearly a miserly, hateful person, that he is steeped in the idolatrous practices of his time and his environment, that he taunts and torments the soulful Jacob – none of this goes punished! He leaves off pursuing Jacob and his daughters and grandchildren and “returns to his place” (Genesis 32:1), unharmed and unpunished.

Perhaps this apparent lack of justice reflects another theme in Genesis: man taking over God’s role and making decisions for himself. Consider Abraham’s decision to go down to Egypt because of the famine. God does not instruct him to do so and he is punished by the near rape of Sarah and the “present” he receives from Pharaoh, Hagar, the progenitor of Ishmael. So, too, here Jacob’s less than ethical behavior in exploiting Esau’s hunger to get the latter to sell him his birthright, as well as his deception of his father which results in this series of events that leave him in the hands of the tyrannical Laban.

On the other hand, there is a case to be made for the intrusion of the Aram-based part of the Abrahamite family – not just here but also in the previous generation with Isaac’s search for a wife. It is just conceivable that the text is trying to hint at a bigger issue – this is what might have happened had Abraham and Sarah stayed in Haran/Aram, outside of the Land of Canaan/Israel. Perhaps they, too, would have been unable to overcome the impact of the environment; perhaps their powers would have been used like Laban’s – for short term gains, for self-aggrandizement, for egotistical reasons. Perish the thought.

In this context it is perhaps interesting to recall that Laban’s name appears in the Passover Haggadah where he is charged with being the “Aramean” who “sought to kill my father.” This phrase is peculiar for a number of reasons. Firstly it appears as the phrase spoken by the pilgrim who comes to offer his first fruits in the Temple (Deuteronomy 26:5). Rashi explains this verse that it refers to Laban the Aramean who tried to kill Jacob (my father) if not in actuality than metaphorically. This can only be referring to the incident where Jacob, frustrated beyond limits by Laban’s venality, takes the opportunity of his host’s absence to flee Aram with his entire household. On hearing of this Laban gives chase and, after seven days, overtakes Jacob and his entourage as they are entering the land of Gilead. There then takes place one of the most mystifying dialogues in the Book of Genesis (chapter 31) when Laban confronts Jacob and demands an explanation for the latter’s leaving Haran without telling his father-in-law. But what exactly is Laban doing? Is he trying to be persuasive, or threatening, cajoling, or pacifying? It is difficult to say, and perhaps this is the way of Laban – the mystification of language in order to hide the real intent of the speaker.

One thing does suggest itself though in this to and fro banter. Laban presents Jacob with a conundrum: Why leave Haran/Aram? Surely his grandfather Abraham came from there, and Rebecca his mother was sent for from the same place. And when he, Jacob, sought to flee his fiery brother – where did he go if not Aram? Moreover in Aram he had found steady work (if less than consistent pay), four wives and multiple children. What else did he need? By contrast the Land of Canaan held nothing for him except bad memories and the threat of death. Despite this, Jacob is adamant and in the face of all Laban’s arguments and threats, he insists in crossing over the border that puts him back on the land of his immediate ancestors.

All of which suggests that Laban’s real motive is to keep Jacob and his family out of the land of Canaan. This is why the rabbis suggest that the Aramean who tries to kill “my father” is none other than Laban. As a representative of Aram – he posits his land against that of Canaan – as the ideal place for Jacob’s sojourning. The rabbis seem to sense this with the hint of Laban’s story as part of the ceremony of the first fruits, a duty made possible uniquely in the land of Israel. It is this very uniqueness that Laban’s subtle dialectics challenge. Jacob, too, learns a lesson from these events. His very last command to his son Joseph is precisely this: “Do not bury me in Egypt.” Only in the soil of his ancestors’ land can his soul be fully at rest. It is this wish that Laban desires to frustrate. Keep the Jews out of the land of their fathers and the world will be a better place.

It is fanciful, though not probable, to think that our expression “a white lie” originates with this Biblical figure, for there is something of the subtle, serpentine liar in Laban – someone who is unskilled in telling the truth and yet who wishes to project an image of “whiteness,” hence his adopted name Laban is not punished with the usual threat of Divine retribution. The Torah, and the Sages thereafter, are aware that the spirit of Laban lives on and remains with us till today, in all its colorful hues, and despite its awful claim to represent the opposite of its tawdry record.

The print shows an innocent looking Laban caressing a wild animal (his inner self?). His portrait is split down the middle, one side is black the other side white (lavan in Hebrew), this being the perfect metaphor for his conflicted personality. In the background are the stars and moon which seem to be the source of his beliefs.

Mordechai Beck is an artist and writer residing in Jerusalem. He is at work on collection of essays on “marginal” Biblical figures with prints.

[Scheduled on November 24, 2020]