Yefet, Shem, and the New Dead Sea Scrolls

Each time I have the opportunity to view the Dead Sea Scrolls in the Shrine of the Book at the Israel Museum, I am in awe at the significance of this discovery, perhaps the most important archaeological contribution of the last century. This month, in an extraordinary find, we learned that these discoveries are no longer only relegated to a distant past: the Israel Antiquities Authority announced the discovery of more Dead Sea Scrolls in caves in the Judean desert, roughly 80 fragments of the biblical books of Zechariah and Nahum, written in Greek.

The newest additions, like the rest of the Scrolls discovered over the last few decades, have been untouched for nearly 2,000 years, and collectively they offer us a window into the lives of Jews living in the Land of Israel during the Second Temple Period. While most of the Scrolls date to the three centuries before the destruction of the Second Temple, scholars believe that these new fragments were brought to the cave during the period of the Bar Kokhba Revolt (132-135 CE) on the basis of other archaeological finds from this period in the surrounding caves. However, the scrolls themselves likely present a much older text, perhaps from the first or second century BCE.

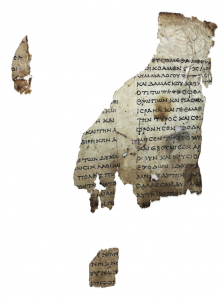

Nahal Hever scroll of Zechariah with God’s name in paleo-Hebrew (middle of the fifth line). Courtesy IAA (photo: Shai Halevi). Click to enlarge.

To some, these new fragments may not seem like an extraordinary discovery. Indeed, they match fragments of the Twelve Minor Prophets scroll discovered in this cave already sixty years ago. Still, the texts from Zechariah and Nahum reflect new sections that were until now unseen –shedding light on the transmission of the Tanakh in antiquity and the standardization of the biblical text. Every last bit of manuscript evidence is significant for scholars who can now compare this Greek text to other ancient Greek and Hebrew manuscripts of Tanakh, creating a fuller picture of the crystallization of the Torah text over time and geographic location.

Notably, what we have before us are fragments from the Tanakh, in a Greek translation, with one curious feature: only the name of God is written in Hebrew. Specifically, it is a Paleo-Hebrew script used during the First Temple Period, in Qumran literature, and during the Bar Kokhba Revolt, signifying both sanctity and nationalistic pride in ancient Israel.

While this in itself is interesting, it begs the question: what were ancient Jews doing with a Greek Torah?

Greek was no stranger to Jews during the Second Temple and Talmudic period; many of us can recall quite easily the many Greek words found in the Talmud itself – such as Sanhedrin, parhesia, safsal, afikoman. Jews in the Land of Israel and in diaspora communities at the time spoke Greek, Aramaic, and a bit of Hebrew to various degrees. It is only natural that we should find a Tanakh translated into the common language of the people.

The translation of the Torah into Greek in the third century BCE – which came to be known as the Septuagint, or in rabbinic parlance Targum ha-Shevi’im – raised a host of responses from ancient Jews recalling the famous event. The Letter of Aristeas, a second-century BCE Jewish composition from Alexandria, characterized this momentous occasion with the highest accolades, describing the Jewish community’s warm embrace of the “excellent and sacred and accurate” translation. Philo of Alexandria, the first-century CE Jewish philosopher and biblical commentator, similarly describes the translation as a divinely inspired, extraordinary feat that impressed both Jews and non-Jews, and warranted annual celebration by the Jews of Alexandria. He writes: “These translators [were] not mere interpreters but hierophants and prophets to whom it had been granted in their most honest and guileless minds to go along with the most pure spirit of Moses” (On the Life of Moses II, 40).

The rabbis of the Mishna, too, accepted the Greek translation of the Torah as a halakhically sanctified text:

The difference between Torah scrolls, and tefillin and mezuzot, is only that Torah scrolls are written in any language, whereas tefillin and mezuzot are written only in Ashurit [i.e., Hebrew script]. Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel says: Even with regard to Torah scrolls, the Sages permitted them to be written only in Greek (Megilla 1:8).

The Gemara explains the opinion of R. Shimon ben Gamliel: “The verse states: ‘God shall enlarge Yefet, and He shall dwell in the tents of Shem’ (Genesis 9:27). This means that the words of Yefet [i.e., the language of Greece] shall be in the tents of Shem [i.e., the Jews]” (Megilla 9b). Similarly, we find in the Yerushalmi: “They investigated the matter and found that the Torah cannot be sufficiently translated, except into Greek” (Megilla 71c).

Some Jews in the second century CE were reading the Torah in Greek on Shabbat in synagogues. We’ve uncovered Jewish funerary inscriptions from Beit She’arim in the lower Galilee, Jaffa, and elsewhere in Greek, as well as Greek synagogue inscriptions. The Talmud Yerushalmi attests to the Shema being read in Greek at a Caesarean synagogue:

R. Levi bar Hitta came to Caesarea and heard voices reciting the Shema in Greek.

He wanted to stop them. R. Yose heard about it and became angry [with R. Levi].

He said: “This I say: If they cannot say it in Hebrew, should they then not say it at all?

Rather they are permitted to say it in any language” (Y. Sota 21b).

Although the Greek language was pervasive among Palestinian and diaspora Jewry from the time of the Second Temple through the early centuries of the Talmudic period, and Greek Torah and prayer were permitted, some rabbinic responses to the Septuagint translation, often by speakers of Persian and Arabic, were not as accepting. Famously, Masekhet Sefer Torah, a post-Talmudic text, records: “That day [of the translation] was as ominous for Israel as the day whereon the Israelites made the Golden Calf.”

And yet, Jews throughout these centuries, including rabbis, incorporated elements of their Greco-Roman environment into their lives to enhance their observance of Jewish religion and culture. This is not unlike the situation today, when translations have afforded greater numbers of Jews to engage with our texts and tradition. After all, the quote from Masekhet Sefer Torah might suggest that as terrible as the Golden Calf was, it paved the way for a renewed covenant with Israel – it allowed the ancient Israelites to worship God more fully in the ways that they were able.

The most recent additions to the Dead Sea Scrolls collection reflects the efforts of ancient Jews to accommodate and incorporate Hellenistic elements while maintaining a sense of essential Jewishness. Sociologist Peter Berger coined the term “sacred canopy” to describe the symbolic religious universe created by a society – and in these texts, we witness the literary meeting of two such sacred canopies: the Jewish and the Greek. Remarkably, as a result of this meeting, the name of God alone is written in Paleo-Hebrew: even in translation, the scribe consciously retained the most important features of a “Jewish” biblical manuscript. In this way, even in their Greco-Roman environment, the Jews reading from and studying these Greek translations asserted their commitment to Judaism.

Miriam Zami is a first-year Ph.D. student studying Ancient Jewish History at Yeshiva University’s Bernard Revel Graduate School of Jewish Studies.