WOODCUT MIDRASH: Balak – Messianic Precursor?

WOODCUT MIDRASH: Balak – Messianic Precursor?

Mordechai Beck

Balak the son of Zippor saw all that Israel had done to the Amorites. And Moab was sore afraid of the people and was overcome with dread because of the children of Israel. Moab said unto the elders of Midian: “Now will this multitude lick up all that is round about us, as the ox licks the grass of the field.” Balak, the son of Zippor, was king of Moab at that time. He sent messengers to Balaam the son of Beor, to Pethor, to the land of the children of his people, saying: “Behold, there is a people come out from Egypt; they cover the face of the earth, and they abide over against me. Come now therefore, I pray you, curse me this people; for they are too mighty for me; perhaps I shall prevail, that we may smite them, and I may drive them out of the land; for I know that he whom thou blesses is blessed, and he whom thou curses is cursed” The elders of Moab and the elders of Midian departed with the magic sticks in their hand; and they came unto Balaam, and spoke unto him the words of Balak (Numbers 22:1-7).

Balak’s anger was kindled against Balaam, and he smote his hands together; and Balak said unto Balaam: “I called you to curse mine enemies, and, behold, you have blessed them three times. Therefore now flee to your place; I thought to promote you to great honour; but, lo, the Lord has kept you back from honor” (Numbers 24:10-11).

Balaam rose up, and returned to his place; and Balak also went his way (Numbers 24:25).

Although the main heroes of this portion are Balaam and his talking ass, the portion in the Torah is named after the king, Balak, who hires him to do the dastardly work of cursing the Israelites. It is true that according to the Talmud (Sota 11a) Balaam had already distinguished himself as a warlock and villainous character by joining the council of advisers to Pharaoh, conceiving of the plot to kill the Israelites’ first-born. While the other two members of the council – Job and Jethro – show little or no enthusiasm for Pharaoh’s mad plans – Balaam is effusively supportive.

Although the main heroes of this portion are Balaam and his talking ass, the portion in the Torah is named after the king, Balak, who hires him to do the dastardly work of cursing the Israelites. It is true that according to the Talmud (Sota 11a) Balaam had already distinguished himself as a warlock and villainous character by joining the council of advisers to Pharaoh, conceiving of the plot to kill the Israelites’ first-born. While the other two members of the council – Job and Jethro – show little or no enthusiasm for Pharaoh’s mad plans – Balaam is effusively supportive.

It appears that Balaam (the Talmud characterizes him as Bli-Am – stateless) is a wandering magician, a mouth-for-hire, with an international reputation. By contrast, Balak appears only here, and then as someone who has usurped power after the defeat of Sihon, king of Moab, at the hands of the Israelites. “As Sihon was killed, so they crowned Balak in his stead,” opines the midrash (Bamidbar Rabba 20:4). Another source suggest that he was “only a prince” (Rashi) or even a nobody.

The true identity of this temporary king of Moab is the subject of another intriguing discussion among the Sages. Accordingly, he is the direct descendant of Lot, nephew of Abraham (Bereishit Rabba 20:19), through an incestuous relationship with his own daughter. Perhaps because of this connection, the Sages refer to him as a wicked person (Nazir 23b) and as one whose sincerity is put into doubt. Sexual perversity seems to be written in his DNA.

The Holy Zohar likens the difference between Midian (the nation from whom Jethro is born) and Moab, over whom Balak reigned, as that of a ripened fruit which it is permissible to eat and throw away, and a unripe fruit which it is neither permitted nor expedient to pluck from its tree, since its essence will emerge only in the future. Thus – in this same portion – God commands Moses to wipe out Midian, even though it is the origin of his wife Zippora’s people. They are the source for contention (modan), and are always looking for an excuse to make trouble, and thus “ripe” for extinction. By contrast, the Moabites, even though they have refused passage to the Israelites on their way in the Promised Land, are protected by God: “Do not harass Moab,” He commands. Right now they are a nuisance, but in the future they will produce the line of David, and though him the Messiah. All this gives Balak an edge over his colleague and nemesis, Balaam.

Neither is Balak short of other strengths. The same midrash accords him a greater capacity at magic and “subtlety” than his hireling Balaam: “While Balaam’s wisdom was temporary and of the moment, Balak’s was steadfast. Yet while Balak knew how to do magic he did not know [as did Balaam] how to express it in words” (Zohar 3:305).

Balak’s concern that his plan will work is borne out by the fact of his presence at almost every stage of Balaam’s actions. Balaam, too, continuously refers back to Balak for his support or understanding as to what he is about to do. They are a team, they cannot succeed apart. Like Moses and Aaron, Balak and Balaam are inter-dependent – Balak is the stuttering king, Balaam his mellifluous High Priest.

These parallels aside, which would help explain Balak’s dependency on the garrulous prophet from Nowhere Land. The issue still remains as to his apparent need for someone else’s spiritual power, when he obviously had plenty of his own.

Like Balaam, Balak is more at home in the black arts than in the enlightened ones. He is “a son of Zippor” (literally, a bird) since he used a bird in his witchcraft, releasing it in the air only to place it inside a cage when it returned with grass in its mouth. Balak would then offer incense before the bird, whose name was Yadu’a (lit., knowing/ knowledge) who would then whisper in Balak’s ear relating to him what it had witnessed on its journey. Once he sent the bird off and it was delayed in its return. This upset the king until he saw a flame chasing Yadua, and singeing its wings. At that point: “And Moab feared the people [of Israel]” (Numbers 22:3; Zohar 3:184).

In another prophetic insight, Balak saw that his descendant through Ruth, King David, would wage battle against Moab and crush them. In an attempt to thwart his future victory, he gathers grasses – specially used by warlocks – and placed them in a magical bowl, burying it 1500 amot below ground, intending them to remain there until the end of time. But David discovered it and cleansed it with waters from the deep and thus annuls Balak’s machinations. As it is written in Psalms “Moab, the pot of my washing” (Psalm 60:10; Zohar 3:198).

Balak also calculated that, like all other nations, Israel was subject to angelic influence. He thus gathered the names of twelve such angels and sent them to Balaam (on the ancient assumption that if one possess the name of something he has control over it) and thus it is written “And he sent messengers” (malakhim, lit. angels).

All this effort came to nothing and the midrash talks of him eating his own flesh in despair, having been manipulated by Israel and not the other way around.

It may be the sense of what might have been had Balak succeeded in all his mischievous plans that led the rabbis to contemplate recalling the whole story in the daily prayers (Berakhot 12b), an institution discarded in practice for being too cumbersome. It does however reflect the Sages’ perception of why throughout this portion no mention is made of either Moses or any other member of the Israelite camp. They understood that this whole story took place while the Israelites were totally oblivious of what was being hatched against them. This was a perfect example of Divine care for His people.

Ultimately, it is Balak who sets up brothels filled with Midianite and Moabite women to entice the Israelites, although he does so on Balaam’s advice (Targum Yonatan to Numbers 24:25). This suggests that such a plan appealed to this descendant of Lot’s daughters, people who broke the very basis of civilized community.

What is Balak’s fate? This, too, is as strange as the tale that bears his name. Not only is he not punished, he is actually rewarded by having King Eglon, Ruth, Orpah and, ultimately, David (and thus the Messiah) spring from his loins. This unlikely progeny is, according to the Sages, in recognition of Balak’s sacrifice to God of 42 bullocks.

Still this startling divine response hardly answers the question as to why his attempt to curse the people of Israel remains unpunished. Balaam by contrast is perversely killed in a flying accident, falling onto his sword while trying to escape the fate of the Midianites (Rashi on Numbers 31:8). If Balaam deserve his death just for expediting the orders he received from the king, then surely Balak deserves no less, if not indeed more. What prompts the difference in the fate meted out to these two enemies of Israel?

Balaam was a professional warlock. His perversity was fundamental to who he was, one prepared to prostitute himself for the highest bidder, even in the face of God Almighty. He doesn’t even pause to reconsider his situation when bested by his lowly ass. Balak, by contrast, can claim some justification for his actions – he was trying to protect his people and that the weapon he was using was not of metal but that of words, the very weapon that was famously identified with his intruder (Rashi). This preference for a verbal as opposed to a military confrontation is a radical move for the pagan world in which Balak flourished. His sense of some higher plane of being is sufficient for the Sages to elevate him in the ranks of Israel’s tormentors and transform him into a source of salvation!

Yet his story is also a warning. The Torah suggests that behind every apparent power, there is another, more discreet, perhaps even hidden, power which is in many ways more powerful than the man up front. It is this that lends the name to the portion. Balak is the real power. He is the one that we must be wary of. For it is he who ultimately controls the controllers.

—

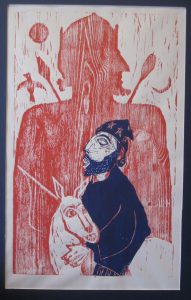

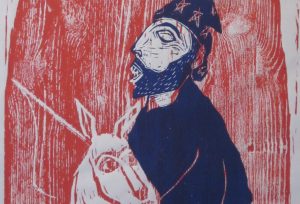

The image is a combination of a woodcut and a linoleum print. The woodcut takes up the largest space as the figure of Balak looming in the background, his scepter and crown manifestations of his kingship. Alongside him are images or icons of a bird, the sun and the moon, symbols of his own mastery over black magic. In the foreground the figure of Balaam sits arrogantly on his beast, the innocent ass. In his hand is a whip with which he chastises his animal. His lack of control, over his ass, or anything else, is of course central to the narrative. But with his one eye he finds it difficult to “see” his situation for what it is.

The overall graphic message reflects the central motif of the story. Balaam is the front man who appears to be the major player, but he is not. The main power is that of Balak who merely uses this mouth-for-hire for his own dubious purposes. Despite his power, Balak is represented as a shadowy figure, seen in silhouette, a dark power behind the action taking place in front of him, a metaphor for what happens in the world at large. To adapt a contemporary saying: follow the power.

Mordechai Beck is an artist and writer residing in Jerusalem. He is at work on collection of essays on “marginal” Biblical figures with prints.

[Published on June 30, 2020]