The BEST: Moses and Monotheism

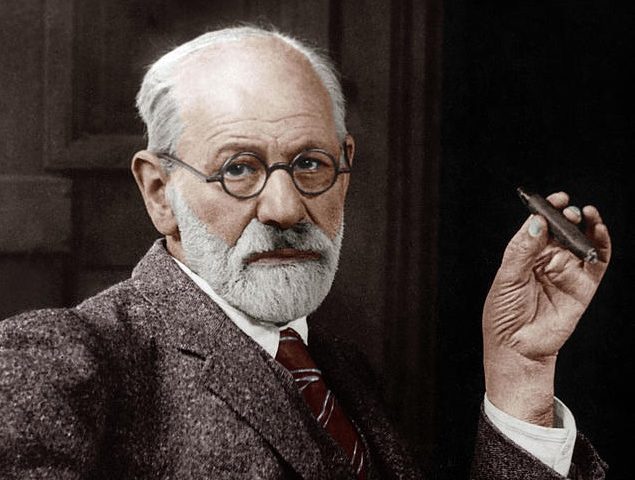

The BEST: Moses and Monotheism by Sigmund Freud

Reviewed by Harvey Belovski

Summary: Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis, completed Moses and Monotheism (1939) while dying of cancer in exile in London. Started before Freud escaped Nazi-occupied Vienna, Moses and Monotheism is a radical re-reading of the life, origins, and religious leadership of Moses. Freud recasts Moses not as a born Hebrew raised in the pharaoh’s palace (as per the Book of Exodus), but as an Egyptian. He asserts that following the death of the pharaoh, Moses led a small band of followers out of Egypt. In Freud’s narrative, Moses was a dictatorial and overbearing figure who was eventually assassinated in a revolt against his leadership. Later, while wandering in the desert, this band encountered another tribe, with whom they combined, adopting their monotheistic beliefs, which later evolved into what we know as Judaism.

For Freud, the murder of Moses and its subsequent repression by the entire people, are defining features of Jewish monotheism. Awareness of the murder itself may be lost from conscious national awareness, but survives in subconscious guilt, which is manifest in various religious obligations and endeavors. One important example is the notion of a “messiah,” which Freud saw as the Israelites’ attempt to reconnect to their sublimated need for a father-leader. This guilt even resurfaces in Judaism’s “daughter religion” Christianity, which attempts to permanently remedy it through the sacrifice of a substitute – Jesus.

For Freud, the murder of Moses and its subsequent repression by the entire people, are defining features of Jewish monotheism. Awareness of the murder itself may be lost from conscious national awareness, but survives in subconscious guilt, which is manifest in various religious obligations and endeavors. One important example is the notion of a “messiah,” which Freud saw as the Israelites’ attempt to reconnect to their sublimated need for a father-leader. This guilt even resurfaces in Judaism’s “daughter religion” Christianity, which attempts to permanently remedy it through the sacrifice of a substitute – Jesus.

Why this is The BEST: Despite its almost total incompatibility with normative Jewish beliefs and its highly mythologized narrative, Moses and Monotheism remains a fascinating and seminal work for the Jewish reader. It provides an important glimpse into the Jewish identity and self-understanding of a resolute self-proclaimed non-believer, a man whose ideas shaped modernity, at the moment he was grappling with his own imminent demise. In fundamentally recasting the foundational narrative of his faith of origin, Freud reveals his profound interest in Jewish ideas and has provided later writers a wealth of material through which to interpret the great man’s Jewish identity. This is especially true for Yosef H. Yerushalmi, whose important book Freud’s Moses: Judaism Terminable and Interminable (Yale, 1993) transformed our understanding of Freud’s relationship to Judaism. Yerushalmi considers whether reimagining Moses as an Egyptian might enhance or degrade Freud’s Jewishness. Most interesting is Yerushalmi’s detailed analysis of just how Jewish in thought and allegiance Freud actually was and the extent to which Jewish history and aspirations colored his work, especially towards the end of his life. Indeed, Yerushalmi asserts that Moses and Monotheism might not have been written at all if not for the events of the Hitler years.

Despite his staunch atheism, Freud is genuinely excited by an important concept that Judaism has gifted to humanity – the choice to worship an invisible God. In the words of Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks, “They opted for the intellectual, not the physical… Jews sought the unknown beyond the horizon… that, wrote, Sigmund Freud… was Judaism’s greatest contribution.” (Covenant and Conversation: “The Genius of Jewish Genius”; “The Faith of God”). Rabbi Sacks demonstrates that Freud’s rather restrained recognition of the “invisible” God barely scratches the surface of the Jewish concept of the divine. He indicates that Freud missed the importance of invisibility – the fact that we cannot conceptualize, understand, or predict God, who through His utter freedom from any external constraints endows human beings with the freedom to choose what they will be. This is a fascinating and innovative inversion of Freud’s understanding of human nature.

It is fascinating that Freud comes perilously close to undermining the credibility of his own thesis. He admits that “[when I use biblical tradition in] an autocratic and arbitrary way, draw on it for confirmation whenever it is convenient and dismiss its evidence without scruple when it contradicts my conclusion, I know full well that I am exposing myself to severe criticism concerning my method and that I weaken the force of my proofs.” Yet, this is part of the charm of Moses and Monotheism – Freud himself uncovers the mass of internal paradoxes that drove him to write the work. This startling self-admission should make Moses and Monotheism more accessible to the contemporary reader. While one should feel no compunction in jettisoning Freud’s chimerical, self-serving narrative, like Rabbi Sacks, one may embrace Freud’s enthusiasm for the invisible God as platform for a mature and source-based investigation of the extraordinary notion of the living God of the Jewish people.

Among the precepts of Mosaic religion is one that has more significance than is at first obvious. It is the prohibition against making an image of God, which means the compulsion to worship an invisible God… If this prohibition was accepted, however, it was bound to exercise a profound influence. For it signified subordinating sense perception to an abstract idea; it was a triumph of spirituality over the senses; more precisely an instinctual renunciation accompanied by its psychologically necessary consequences.

The progress in spirituality consists in deciding against the direct sense perception in favor of the so-called higher intellectual processes, that is to say, in favor of memories, reflection and deduction. An example… would be: our God is the greatest and mightiest, although He is invisible like the storm and the soul.

Harvey Belovski is senior rabbi of Golders Green Synagogue in London and Chief Strategist and Rabbinic Head of University Jewish Chaplaincy.

Click here to see The BEST series introduction and here to read about the special Rabbi Sacks Bookshelves series