Selihot in Manifestation and Essence

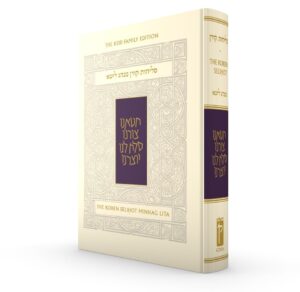

With the arrival of Rosh Hodesh Elul we enter the month of “mercy and forgiveness.” Among the most well-known but challenging customs of this month is the recitation of Selihot. The publication of a new edition of these penitential prayers and piyutim with an introduction and insightful commentary by Rabbi Dr. Jacob J. Schacter will enhance our recitation of the Selihot for generations to come. This essay is excerpted and adapted from Rabbi Schacter’s learned introduction to the volume. In this section he explores themes related to the meaning and force of the Thirteen Attributes of Mercy – the central experience of the Selihot prayers. (Read the full introduction for Rabbi Schacter’s examination of other important Selihot themes as well as the many excurses and references contained in the footnotes of the original essay.) The new volume appears as The Koren Selihot Minhag Lita – Reid Family Edition, with an introduction and commentary by Jacob J. Schacter and translation by Sara Daniel (Koren Publishers, 2022), 1229 pp. Use promotion code TRADITION for a 10% discount off the new Selihot and the entire Koren Publishers catalog.

Selihot in Manifestation and Essence

The Hebrew Bible uses a form of the words seliha or selihot to refer to forgiveness in a number of verses: “I have forgiven in accordance with your words” (Numbers 14:20); “And it shall be forgiven to the entire assembly of Israel” (Numbers 15:26); “For with You is forgiveness, that You may be held in awe” (Psalms 130:4); “But You are the God of forgiveness, gracious and compassionate” (Nehemiah 9:17); “To the Lord our God [belong] mercy and forgiveness” (Daniel 9:9). But the cluster of prayers that we call Selihot began to develop as a unit only in the early Middle Ages. By the ninth century, a Selihot service of some kind had been established. The Geonim refer to such a service as something which had already been in existence for a while and not as something new which they introduced.

A fundamental component of this service, from its inception, is the recital of what are known as the Thirteen Attributes of Mercy (middot ha-rahamim). After the Jewish people sinned by worshipping the Golden Calf, God appeared to Moses, and instructed him to carve a second set of tablets. Moses once again ascended Mount Sinai, and God descended upon it in a cloud and stood with Moses (Exodus 34:4–5), where, according to rabbinic literature, God demonstrated the prayer of the Thirteen Attributes of Mercy to Moses and guaranteed that He would respond to it.

There are three questions I wish to raise in connection with the recitation of Selihot in general, and these thirteen attributes in particular, and I would like to suggest one overarching principle that resolves them all.

First, Rabbi Jacob ben Asher quotes the opinion of Rabbi Natan Gaon, that the recitation of the thirteen attributes requires the presence of a minyan. He himself, however, questions this position because he considers the one reciting the thirteen attributes to be “as one who is reading from the Torah” and not as one uttering “an expression of sanctity” (davar sheba-kedusha) and, therefore, no minyan should be necessary. Unlike one who utters “an expression of sanctity,” simple “reading from the Torah” requires no minyan. Rabbi Jacob is joined by others who also reject Rabbi Natan Gaon’s position and maintain that a single individual can also recite these words. My first question is: What, indeed, is the justification or rationale for Rabbi Natan Gaon’s position? Why would he require a minyan for the recitation of the thirteen attributes?

First, Rabbi Jacob ben Asher quotes the opinion of Rabbi Natan Gaon, that the recitation of the thirteen attributes requires the presence of a minyan. He himself, however, questions this position because he considers the one reciting the thirteen attributes to be “as one who is reading from the Torah” and not as one uttering “an expression of sanctity” (davar sheba-kedusha) and, therefore, no minyan should be necessary. Unlike one who utters “an expression of sanctity,” simple “reading from the Torah” requires no minyan. Rabbi Jacob is joined by others who also reject Rabbi Natan Gaon’s position and maintain that a single individual can also recite these words. My first question is: What, indeed, is the justification or rationale for Rabbi Natan Gaon’s position? Why would he require a minyan for the recitation of the thirteen attributes?

Second, Jewish law insists that verses from the Torah need to be recited in their entirety. The Talmud (Taanit 27b; Megilla 22a) states that we may not divide any verse that Moses did not divide. Yet, surprisingly, this principle is blatantly ignored when it comes to the recital of the thirteen attributes during the Selihot service. Our custom is to end with the word “and absolving (ve-nakeh).” But how can we do so, given that this word appears right in the middle of a verse (Exodus 34:7) and, indeed, in the middle of a phrase! The verse continues, “but does not absolve completely.” Does not the sudden stop violate this principle of not artificially dividing verses? How can we justify stopping here in the middle of a verse, especially considering that doing so changes the meaning?

Third, there are many different customs for the earliest day on which the pre-Rosh HaShana Selihot can be recited. Various Geonim (Rabbi Amram, Rabbi Kohen Tzedek, Rabbi Hai) and Rambam write that Selihot are to be recited only during the Ten Days of Repentance. Rabbeinu Nissim presents three different customs: In Barcelona and its surrounding communities, Selihot recitation began on the twenty-fifth of Elul. In Gerona and its surrounding communities, Selihot were recited only during the Ten Days of Repentance, in accordance with the view of the Geonim. In yet other, unnamed communities, the recital of Selihot commenced already on Rosh Hodesh Elul, the beginning of the forty-day period when Moses ascended Mt. Sinai to receive the second tablets of law which he brought down to the Jews on Yom Kippur, the day God grants atonement for our sins.

Yet other rabbinic authorities offer additional dates: For Rabbi David Abudarham, Selihot recitation begins on the fifteenth of Elul; for Rabbi Simha ben Samuel it is the Motza’ei Shabbat prior to Rosh HaShana; for Rabbi Tzidkiya HaRofeh no single date is offered but, rather, a complicated procedure is used to determine when to start. North African communities followed an entirely different practice. They recited Selihot on twenty-three nights: eight Monday and Thursday nights during the month of Elul, four Shabbatot in Elul, erev Rosh HaShana, and the Ten Days of Repentance.

Remarkably, the accepted practice in Ashkenazi communities is different from every one of these customs. Rabbi Moses Isserles begins his ruling on when to begin the Selihot recitation with a time reminiscent of that suggested by Rabbi Simha ben Samuel, namely, the Motza’ei Shabbat prior to Rosh HaShana, but he then adds that if Rosh HaShana falls on a Monday or Tuesday (it cannot fall on a Sunday), the beginning date is moved back to the previous Motza’ei Shabbat. And so, my third question is: What is the basis for this seemingly strange Ashkenazi custom of beginning to recite Selihot the previous week when Rosh HaShana falls on a Monday or Tuesday?

There are two themes I want to underscore regarding the thirteen attributes that provide answers to these questions. First, Judaism regards all mitzva observance as consisting of two components. In the words of Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik, “There are two aspects to the religious gesture in Judaism: strict objective discipline and exalted subjective romance. Both are indispensable” (Family Redeemed, 40). In another more famous passage Rabbi Soloveitchik wrote:

I learned from her [my mother] very much. Most of all I learned that Judaism expresses itself not only in formal compliance with the law but also in a living experience. She taught me that there is a flavor, a scent and warmth to mitzvot.… The laws of Shabbat, for instance, were passed on to me by my father.… The Shabbat as a living entity, as a queen, was revealed to me by my mother.… The fathers knew much about the Shabbat; the mothers lived the Shabbat, experienced her presence, and perceived her beauty and splendor (“A Tribute to the Rebbetzin of Talne,” 77).

We are obligated to perform various mitzva acts and, in addition, to do so with feeling and intention. A robot can also shake a lulav or immerse in a mikve but, as human beings, we are engaged in a relationship with God and need to bring the fullness of our humanity into that relationship. Mitzva observance is two-fold: act and affect, motion and emotion, external and internal, formal compliance and living experience; it consists of both “religion in manifestation” and “religion in essence.”1

After positing that there are “two aspects to the religious gesture in Judaism: strict objective discipline and exalted subjective romance,” Rabbi Soloveitchik goes on to provide examples: “For instance, the commandment of Shema requires, on the one hand, an inner act of surrender to the will of the Almighty. On the other hand, this subjective experience of submission must be translated into a physical act of reciting the Shema. The same is true of prayer. It consists of both experiencing the complete helplessness of man, his absolute dependence upon God, and the performance of the ritual of prayer, of reciting fixed texts.” Prayer, after all, is “worship of the heart” and, as such, its inner dimension is obvious and self-evident.

If this is true of prayer in general, it is especially true of the Selihot service. While it is necessary to recite the words that constitute this service, mere recital is clearly insufficient. In addition to articulating the words, as one approaches God before Rosh HaShana, and between Rosh HaShana and Yom Kippur, one needs to be emotionally connected to the words, to recite them with sincerity, with kavana, sincerely asking God for His help and His blessing. The inner emotional component of Selihot recitation is essential.

This central notion of Selihot is echoed in a number of sources. Rambam writes, “During these Ten Days [of Repentance] the custom is for everyone to rise during the night and pray in the synagogue with words of supplication and until day break” (Hilkhot Teshuva 3:4). Note first that Rambam presents the recital of Selihot as prayer, and that the venue for that prayer is in the synagogue. But he describes it as more than prayer. Selihot are described as “words of supplication and appeasement” (Hilkhot Teshuva 3:4) which bespeak feeling and sincerity, an engagement of the heart and of the emotions in addition to the recital of proscribed words.

Rabbi Mordekhai Jaffe goes so far as to frame the Selihot service as a mini “order of prayer.” He writes that the introductory verses correspond to Pesukei DeZimra; the recital of the thirteen attributes, which he describes as the core of the Selihot service, corresponds to the Eighteen Benedictions (the Amida); and the Selihot service that follows corresponds to the rest of the daily Shaharit service. Just as it is most appropriate to recite the Eighteen Benedictions with feeling and sincerity, so too should one recite the Selihot.

This idea is powerfully expressed by Rabbeinu Bahya ben Asher who conditions the efficacy of the thirteen attributes entirely on the intention one has in reciting them. He explains that Rabbi Yehuda’s statement that “a covenant was made with the thirteen attributes that they will not return empty-handed” (Rosh HaShana 17b) is only true if one recites them understanding the meaning of the words and “prays them with intention.” Rabbi Yosef Hayyim David Azulai (Hida) also states this very clearly. He writes that “one must recite the Selihot deliberately, slowly, and with kavana.” He even goes so far as to rule that it is prohibited to mention that the thirteen attributes without kavana. All these statements underscore the emotional inner component of Selihot recitation.

Given this principle, one can answer the first two questions posed above. Rabbi Solomon ben Abraham ibn Adret (Rashba) writes that since the Selihot prayers need to be recited “as a prayer and requests for mercy,” they assume the status of “an expression of sanctity” (daver sheba-kedusha) which requires a minyan. For him, unlike the position of Rabbi Jacob ben Asher (the Tur) cited above, Selihot recital is not to be considered merely “reading from the Torah” which would not require a minyan. It is much more than simple reading or recitation. It presupposes an inner emotion, a sense of supplication, a heartfelt and sincere request on the part of the petitioner before the Holy One, Blessed is He. In his view, this provides an element of sanctity to the recitation and therefore he maintains, in accordance with the position of Rabbi Natan Gaon cited above, that the recital of Selihot requires a minyan like all “expressions of sanctity.” This position of Rashba is found in the formulation of Rabbi Joseph Caro’s Shulhan Arukh. He states that “It is not proper for a single person to recite the Thirteen Attributes as a prayer and request for mercy for they are an expression of sanctity” (O.H. 565:5).

Another answer to the first question may be deduced from a statement in the Midrash, “David knew that in the future the Temple would be destroyed and that sacrifices would be abolished as a result of the sins of Israel. David was distressed for Israel [and said], ‘What [then] will atone for their sins?’ The Holy One, Blessed is He, said to David, ‘When calamities will befall Israel as a result of their sins, let them stand before me together in one group, confess their sins before Me, and recite before Me the order of the Seliha and I will answer them’” (Tana DeBei Eliyahu Zuta [Warsaw, 1912], 35b, siman 23). In order for the thirteen attributes to be efficacious, Jews need to be united, as one people, standing before the Holy One, Blessed is He, “together in one group.” Perhaps this too can be understood as providing another source underscoring the centrality of a minyan for the recital of Selihot.

The notion that Selihot need to be recited as words of supplication and appeasement, deliberately, slowly, and with kavana, is utilized by Rabbi Abraham Gumbiner to answer the second question presented above. After all, does not the sudden stop in the middle of the verse presenting the thirteen attributes violate the principle against artificially dividing verses? He writes that this principle, that we may not divide any verse that Moses did not divide, applies only when they are being “read.” But if they are being recited as prayer, they are exempt from this principle. If one reads parts of verses as expressions of “supplication and request,” it is permissible.

Rabbi Gumbiner here echoes a similar principle presented centuries earlier by Rabbi David Abudarham who ruled that the normal principle prohibiting changes in the formulation of verses from singular to plural and vice versa does not apply where they are being recited as part of a prayer service. Rabbi Abudarham writes that when the intention is not to “read” these verses, but to “plead as in the manner of prayer and expressing request,” such changes are permissible. This same reasoning used by Rabbi Abudarham to justify switching back and forth from singular to plural in prayer is used by Rabbi Gumbiner to justify stopping in the middle of a verse while praying, and is very reminiscent of the language of Rabbi Solomon ben Abraham ibn Adret as to why Selihot require a minyan.

The message is clear. The recital of Selihot cannot be perfunctory and rote; it must be heartfelt and meaningful, real and sincere. Selihot recital involves not just “strict objective discipline” but also “exalted subjective romance,” not only “formal compliance with the law” but also the law as “a living experience.”

The second idea I want to underscore with regard to the thirteen attributes is that, for many, their real efficacy lies not in merely reciting them, even with the appropriate feelings of heartfelt sincerity, but in acting in accordance with them. Proper Selihot also require actions and deeds, not just words or thoughts, however meaningfully and sincerely they may be expressed.

For example, in commenting on the few words that conclude and follow the list of the thirteen attributes in the Torah, Rashi writes that God absolves only those who repent and not those who do not repent. Clearly some behavior is necessary; mere verbal declaration is insufficient (Rashi to Exodus 34:7). Immediately prior to codifying the custom to recite Selihot during the Ten Days of Repentance, cited above, Rambam writes that the custom is that all Jews give a lot of charity, perform many good deeds, and are occupied with mitzvot during these times. This is the first step. Only after drawing attention to these actions does Rambam go on to mention the recital of Selihot.

Furthermore, a number of rabbinic authorities wonder about the nature of the covenant made in connection with the thirteen attributes, “that they will not return empty-handed.” They point out that often people recite these words and are not favorably answered; that, in fact, they do “return empty-handed.” To explain this apparent discrepancy, they note that the talmudic formulation regarding the thirteen attributes cited above is not that God told Moses, “Whenever the Jewish people sin, let them recite before Me in accordance with this order, and I will forgive them,” but rather “Whenever the Jewish people sin, let them act before Me in accordance with this order, and I will forgive them.” For them, it is not enough to say these words; we must, rather, act in accordance with the thirteen attributes of God outlined here: “Just as He is compassionate and merciful, so too should you be compassionate and merciful.” One must act compassionately and mercifully; simply reciting the words is, indeed, no guarantee. This is reminiscent of the famous passage in the Talmud (Sota 14a; also Shabbat 133b) obligating one to imitate the traits of God outlined in the thirteen attributes, namely, to act in clothing the naked, visiting the sick, comforting the mourners, and burying the dead. The deep profound personal engagement central to Selihot includes action as well as the recital of words.

This emphasis on behavior is highlighted in a talmudic statement preceding the one about the thirteen attributes cited above. The Talmud (Rosh HaShana 17a) cites in the name of Rava that those who forgive others for injustices done to them will have their sins forgiven by the heavenly court. The proof text cited is the verse, “He pardons sin and overlooks transgression” (Micah 7:18). The first part of the verse is interpreted as a reference to God, the second part to a human being. Whose sins does God pardon? The sins of those who overlook the transgressions that others have committed against them. The Talmud continues by relating a story about Rabbi Huna, son of Rabbi Yehoshua, who became sick, and Rabbi Pappa went into his home to inquire about his well-being. When Rabbi Pappa saw that Rabbi Huna was dying, he said to his attendants, “Prepare his provisions [his shrouds].” In the end, Rabbi Huna recovered.

Rabbi Huna’s friends said to him, “What did you see when you were lying there suspended between life and death?” He answered, “Indeed, I was truly close to dying, but the Holy One, Blessed is He, said to the heavenly court: Since he does not stand on his rights [he is ready to waive what is due him], you too should not be exacting with him in his judgment, as it is stated: “He pardons sin and overlooks transgression.” Whose sins does He pardon? The sins of one who overlooks the transgression of others for injustices committed against him.

The message is clear: One cannot simply recite the words of the thirteen attributes; people’s sins are forgiven when they live by them, pardoning those who wrong them.

The power of proper and appropriate interpersonal behavior, and the need to follow the principle of “just as He is compassionate and merciful, so too should you be compassionate and merciful,” is also illustrated by a striking comment made by Rabbi Yoshiya Pinto, a seventeenth-century Damascus rabbi and scholar. The Mishna (Yoma 8:9) states: “For sins committed between a person and God, Yom Kippur atones. For sins committed between one person and another, Yom Kippur does not atone until he appeases the other person.” The Mishna then continues and cites Rabbi Elazar ben Azarya who taught this principle from the verse (Leviticus 16:30), “From all your sins you shall be cleansed before the Lord.” And, he continues, “For sins committed between a person and God, Yom Kippur atones. For sins committed between one person and another, Yom Kippur does not atone until he appeases the other person.”

This passage is cited by Rabbi Levi ibn Habib in his Ein Yaakov collection of homiletical passages from the Talmud. In his commentary on that work, Rabbi Pinto wonders what Rabbi Elazar ben Azarya is adding to the immediately prior opinion cited in the Mishna. If it is to provide a textual basis for that comment, why did the Mishna not simply state the following: “For sins committed between a person and God, Yom Kippur atones. For sins committed between one person and another, Yom Kippur does not atone until he appeases the other person. Rabbi Elazar ben Azarya said, ‘From whence do we know this? From the verse “From all your sins you shall be cleansed before the Lord”’.” Why was it necessary for Rabbi Elazar ben Azarya to repeat verbatim the statement already made in the Mishna, “For sins committed between a person and God, Yom Kippur atones. For sins committed between one person and another, Yom Kippur does not atone until he appeases the other person”? Rabbi Pinto provides a most striking and far-reaching answer. He suggests that even though the words are identical, there is a fundamental disagreement between the first statement in the Mishna and the opinion of Rabbi Elazar ben Azarya. The first statement states that there are two kinds of sins, those between a person and God and those between one person and another. With regard to sins between a person and God, Yom Kippur atones. Those sins are forgiven. However, when it comes to sins committed by one person against another, Yom Kippur does not forgive. In order to achieve forgiveness for that category of sin, the perpetrator must directly seek forgiveness from the aggrieved. However, suggests Rabbi Pinto, Rabbi Elazar ben Azarya disagrees. In his view, Yom Kippur can atone for sins committed by a person against God, but if a person does not seek forgiveness from someone whom he hurt then not only does Yom Kippur not atone for that sin, it will not even atone for sins committed against God. For Rabbi Elazar ben Azarya there are not two separate categories, each with its own independent mechanism of atonement. Rather, in his view, “For sins committed between a person and God, Yom Kippur atones. For sins committed between one person and another, Yom Kippur does not atone for any sin, even those committed against God, until he appeases the other person.” If people do not ask others to forgive them for having wronged them, Yom Kippur is totally meaningless and irrelevant. It will not provide them with atonement even for sins they committed against God.

But why is this so? Why is asking forgiveness from another person so central and so crucial that without it, even sins committed against God that have nothing to do with another person, will not be atoned? Does this not seem extreme? Rabbi Hayyim Palache, an eighteenth-century Turkish rabbi, suggests that rules outlining both behavior between a person and God and between one person and another are specified in the Torah. For example, the same Torah that commands the laws of kashrut commands “love your neighbor as yourself.” And so, violating the latter commandment is also a violation of Torah. Why, then, suggests Rabbi Palache, should God forgive one for violating laws between a person and God if not asking forgiveness from other people for sins committed against them is a violation of the same Torah? Rabbi Pinto’s interpretation of Rabbi Elazar ben Azarya’s position is thus clarified. “For sins committed between a person and God, Yom Kippur atones. For sins committed between one person and another, Yom Kippur does not atone for any sin, even those committed against God, until he appeases the other person.”

Another explanation of Rabbi Pinto’s position suggested by Rabbi Saul Löwenstamm, Chief Rabbi of Amsterdam in the second half of the eighteenth century, is most relevant here. An introductory comment is necessary to appreciate the import of his answer. There is a striking passage in the Yerushalmi (Makkot 2:6): “They asked Wisdom, ‘What punishment is due the sinner?’ She said to them, ‘Evil pursues sinners’ (Proverbs 13:21). They asked Prophecy, ‘What punishment is due the sinner?’ She said to them, ‘The soul that sins – it should die’ (Ezekiel 18:4, 20). They asked the Holy One, Blessed is He, ‘What punishment is due the sinner?’ He said to them, ‘Let him repent and he will be atoned.’” The message here is a profound one. By any measure repentance is conceptually impossible. After all, a sin was committed. Where does it go? How can it be rescinded or erased? The act was done and the one who did it must be held responsible. And, in the view of Reish Lakish (Yoma 86b), repentance is so great that even willful transgressions are not only considered as errors but even as merits! How is this conceivably possible? Indeed, both Wisdom and Prophecy state the obvious: Sinners need to be held responsible for the sins they commit. Period. It is only God who allows for the efficacy of repentance. Yes, it is illogical; yes, it defies reason, but it is simply a gift to us from God. “Repent, sincerely regret your misdeeds and undertake not to repeat them and,” says God, “I will forgive you.”

But why should God give us what is clearly nothing other than a gift? Rabbi Löwenstamm notes that one normally speaks of human beings acting like God, following the ways of God, “Just as He is compassionate and merciful, so too should you be compassionate and merciful.” But, he suggests, in this case it is God who models His behavior after ours. When God sees that we forgive others for wrongs they committed against us, He does the same for us. After all, a wrong was committed against another person. Where does it go? How can it be forgiven? The act was done and the one who did it must be responsible. But yet the aggrieved party is prepared to forgive, somehow to put that event in the past, and move on. And so, says God, I will do the same.

Rabbi Löwenstamm suggests that this is the rationale behind the position of Rabbi Pinto. When will God forgive those who sinned against Him? When he sees them forgiving others who perpetrated wrongs against them. If we don’t forgive our fellow human beings for wrongs they did against us, why should God forgive us for wrongs we did against Him? Once again, the recital of words is wholly insufficient; simply reciting the words of the thirteen attributes is meaningless. What makes all the difference is the way one behaves toward someone else, how one lives the behaviors described in the thirteen attributes.

We are now in a position to answer the third question posed above. When Rosh HaShana falls on a Monday or Tuesday, what is the basis for the Ashkenazi custom to begin the recital of Selihot at the beginning of the previous week? Rabbi Mordekhai Jaffe, the sixteenth-century Polish rabbi, explains that “most of the world” has a custom to fast at this time of year for ten days, including Yom Kippur, corresponding to the Ten Days of Repentance. Since one cannot fast on four of those days – two days of Rosh HaShana, Shabbat Shuva, and Erev Yom Kippur – the custom developed to fast for four days prior to Rosh HaShana. It was on account of this, he suggests, that the recitation of Selihot was instituted on those days. This equivalence makes sense since the goal of reciting Selihot is similar to that of fasting, to focus attention on introspection and repentance. And so, if Rosh HaShana falls early in the week, it is necessary to begin reciting Selihot the previous week.

The point made earlier about the importance of acting in accordance with the thirteen attributes, “Whenever the Jewish people sin, let them act before Me in accordance with this order, and I will forgive them,” provides the frame for a second explanation for the Ashkenazi custom to begin the recital of Selihot four or more days prior to Rosh HaShana. Jewish law requires that sacrificial animals require examination for blemishes four days before they are brought on the altar. Now, regarding the Musaf sacrifice on holidays in general, the formulation used (Numbers 28:27; 29:8, 13,36) is “And you shall offer a burnt offering,” but with regard to the Musaf sacrifice on Rosh HaShana, the text (Numbers 29:2) reads, “And you shall make a burnt offering.”

Rabbi Menahem Mendel Auerbach, author of the Ateret Zekeinim commentary on Orah Hayyim, takes this to mean that we should prepare ourselves as if we ourselves were the sacrifice. We need to envision ourselves as a sacrifice, and since a sacrifice requires four days of examination prior to it being brought on the altar, we require at least four days of Selihot recitation to examine our behavior and make sure we do not enter Rosh HaShana with any blemishes. Once again the emphasis is on doing, acting. Selihot require that we recite, that we feel and, finally, that we act.

In summary, by recognizing that engaging with Selihot requires more than mere recitation, we can understand the answers to all three questions posed above. Because they need to be recited in a special way, “as prayer and requests for mercy,” they require a minyan – this grants it the status of “an expression of sanctity” (Rashba); because it needs to be read as expressions of “supplication and request,” it is not bound by the principle that we may not divide any verse that Moses did not divide (Magen Avraham); because it requires action, seeing oneself as a sacrifice, it needs to be recited at least four days prior to Rosh HaShana (Ateret Zekeinim).

Rabbi Yosef ben Moshe writes that the person who is designated to lead the prayers on Rosh HaShana and Yom Kippur must lead the Selihot service because if he fails to do so he “is comparable to a person who wants to visit with the king but has the inner key and not the outer key” (Leket Yosher 117). While he is addressing the role of the prayer leader, I believe that this image applies to each of us as well. As we approach God in this season, the Selihot service serves as our outer key. We need to utilize it – properly, appropriately, and effectively – to begin to make our way into Rosh HaShana and Yom Kippur. We need to successfully use the key to the outer door to have a chance of approaching the inner door with any degree of success.

Rabbi Dr. Jacob J. Schacter, a member of the TRADITION editorial board, is University Professor of Jewish History and Jewish Thought and Senior Scholar at the Center for the Jewish Future at Yeshiva University.

- These two phrases come from the title of a book written by G. Van Der Leeuw, a Dutch Gentile scholar first published in 1938. I was introduced to it in an article by my teacher, Dr. Isadore Twersky. See his “Religion and Law,” in S.D. Goitein, ed., Religion in a Religious Age (Cambridge, 1974), 69, and 78, n. 2. Dr. Twersky goes on to state that “Halakha is the indispensable manifestation and prescribed concretization of an underlying and overriding spiritual essence.”