Down the Berkovits-Heschel Rabbit Hole

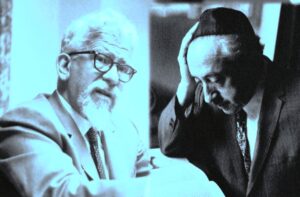

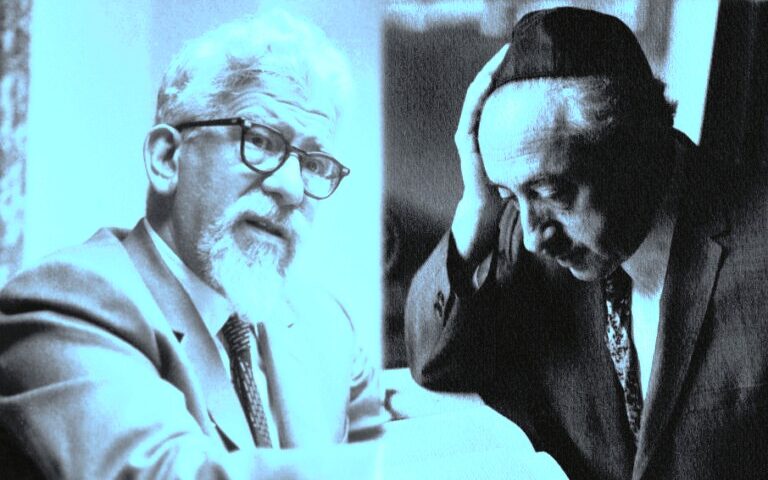

TRADITION’s most recent issue featured a lengthy essay by Todd Berman exploring a nearly 6-decade-old critique launched by R. Eliezer Berkovits on Dr. Abraham J. Heschel’s “Theology of Pathos.” (See Berman’s essay open-access here, with a link to Berkovits’ original 1964 article.) In brief, the debate centered on Heschel’s contention that

[a prophet] feels God’s feeling. The prophets react to the Divine pathos with sympathy for God . . . Sympathy is a feeling which feels the feeling to which it reacts. . . Because of this sympathy, the prophet, is guided, not by what he feels, but rather by what God feels. In moments of intense sympathy for God, the prophet is moved by the pathos of God.

For Berkovits, Heschel errs by aligning himself with the wrong side of the anthropomorphism and anthropopathism debate.

Berkovits was a significant figure in mid-century Orthodox Jewish thought, and was an important contributor to the pages of TRADITION, publishing ten essays with us during our first decade and a half. A noteworthy curiosity of Berkovits’ critique of Heschel was its appearance with an editorial note expressing some reservation about this “controversial” offering, which “evoked sharp differences of opinion among members of our editorial board,” on which he served as a member between 1963-1967.

Just one year later, in our Summer 1965 issue (most well-known for featuring “The Lonely Man of Faith”), Berkovits produced another essay, “Orthodox Judaism in a World of Revolutionary Transformations.” This piece also featured a disclaimer that its “provocative… candid self-criticism” of contemporary Orthodoxy appeared despite the disagreement of “most of our editorial board.”

Mr. Lawrence Kobrin, now entering his 64th year as a member of that august editorial board, despite his constitutional role as our institutional memory, has no clear reminiscences of the particular internal squabbles documented by these notes. He did, however, recently attempt to contextualize the times in which Berkovits’ essays could cause such a stir. Further archival deep dives, especially when the papers of some of the figures involved are available, may turn up additional insight to this chapter. Stay tuned.

Well, plus ça change. Berman’s essay has similarly evoked sharp differences of opinion among our readers. (Those interested should also follow the lively discussion on his Facebook page.) Read the critical reactions to the recent essay by David Curwin and Rafi Eis; Berman will respond on our website in the coming days. In the meantime, going down the rabbit hole into the TRADITION Archives has helped to resurface some interesting related content, some of which was referenced in passing in Berman’s footnotes. To help situate our readers for the coming exchange of letters we have collated the following material:

In the Communications section of that Summer 1965 issue we published a response to Berkovits v. Heschel by Mr. E. Munk of Ontario, to which Berkovits offered a brief reply. (Eliyahu Munk, a prolific translator of classical Torah texts, passed away recently at 100. He was a cousin of French-born R. Elie Munk, author of The World of Prayer, among many other books.)

Among Berkovits’ important collections of essays was his Major Themes in Modern Philosophies of Judaism (Ktav, 1975). This volume republished the TRADITION essay explored by Berman. In reviewing the collection for our journal (Fall 1975, from p. 147ff.), a young Shalom Carmy (who would go on to become our distinguished editor) attempted to clear-up two misunderstandings or mischaracterizations of Berkovits’ treatment of Heschel. He first dismisses an idea (perhaps advanced among some “pulpit rabbis”) that Berkovits’ animus toward Heschel was motivated by the former’s ardent anti-Christian sentiment—Heschel’s thought having “real or imagined propinquity between Heschel and Christian theology.” That Heschel was a prominent advocate of interfaith dialogue could not have helped, although Carmy does not raise this point. Then, he rejects the suggestion that Berkovits wants to align himself with the view of Maimonides theory of attributes. Carmy observes that as early as Berkovits’ God, Man and History (1959), a half-decade before the TRADITION essay, he had distanced himself from that Maimonidean position (on which the purported comparison hung). God, Man and History (recently republished by Shalem Press) will feature prominently in the upcoming exchange between Berman and his critics. Especially since (as shown by Carmy), it seems to undermine Berkovits’ later critique of Heschel.

As an aside, Carmy appears to compound a misreading in the exchange of letters between Munk and Berkovits. The former writes: “Dr. Berkovits then proceeds to quote Prof. Vervotim along the same lines.” Carmy states, “I have been unable to identify the Prof. Vervotim cited by Dr. Berkovits’ critic as an authority.” Of course, those familiar with our esteemed editor emeritus’ wry humor will understand that “Prof. Vervotim” was a typo in Munk’s letter to the editor, which should read, “Dr. Berkovits then proceeds to quote Prof. [Heschel] (Vervotim) [verbatim]….,” as indeed he does in the following paragraph. Berkovits was taking care not to misread Heschel by quoting explicitly. The only authority Berkovits was quoting was Heschel. (Berman had made this observation in an earlier, even longer draft of the essay, from which I borrow here, but it was left on the cutting-room floor.)

As interesting as Berkovits’ position in the Modern Orthodox firmament was in those years, it is no less interesting to note the presence of Heschel as a subject of essays in our journal. For example, David Shatz recalled that early on Prof. Marvin Fox, R. Norman Lamm’s “partner” in founding TRADITION, presented two essays on Heschel’s thought. In 1960’s “Heschel, Intuition, and the Halakhah” Fox criticizes Heschel, over the course of several pages, for not recognizing the centrality of halakha:

While we applaud the skill with which [Heschel] has explicated and defended the often neglected Aggadah we must note that this enthusiasm seems to have blinded him somewhat to the special place of Halakhah in Judaism. For, according to Dr. Heschel, “Halakhah does not deal with the ultimate level of existence.” He believes that “The law does not create in us the motivation to love and to fear God, nor is it capable of endowing us with the power to overcome evil and to resist its temptations, nor with the loyalty to fulfill its precepts. It supplies the weapons; it points the way; the fighting is left to the soul of man” (12).

However, in 1966, in discussing other works by Heschel, he praises him for recognizing the importance of duty and obedience to halakha! (Berman mentions both pieces at the outset of his essay but does not dwell on or unpack the significance of this difference.) Oddly, the editorial note to Fox’s negative 1960 essay is highly laudatory of Heschel’s impact on “contemporary thinking Jews,” while the 1966 note is more tepid in tone.

In Fall 1977, well more than a decade following the “theology of pathos” article, Steven T. Katz, in a very lengthy review essay of the same volume covered two years earlier by Carmy, revisited the topic (section VI). Anticipating some aspects of Berman’s defense of Heschel against Berkovits’ attack, Katz asserts that his essay “has indicated serious weaknesses in Berkovits’s work. It has objected to the terminology, methodology, logic and tone of much of his exposition and criticism with respect to major modern Jewish thinkers.”

What are we to make of that historical moment in Modern Orthodox thought? In the private ruminations of the contemporary TRADITION board, David Shatz observed that Berkovits did not attack Heschel on the grounds that our journal and the religious position it represented were most concerned about: namely, his view of halakha and his attack on pan-halakhaism. It is ironic that in some ways, these many decades later, Modern Orthodoxy is now closer to Heschel on these issues. Larry Kobrin speculated on what would be a current analog to TRADITION’s editorial note to Berkovits’ critique? What would be today’s philosophical issue that would generate a similar debate on whether or not to publish, or to do so with a disclaimer? One wonders.

Jeffrey Saks is the Editor of TRADITION.

[Read responses to Berman’s essay by David Curwin and Rafi Eis and read Berman’s reply to their critiques.]