Alt+SHIFT: Shalom Rosenberg z”l

Alt+SHIFT is the keyboard shortcut allowing us quick transition between input languages on our keyboards—for many readers of TRADITION that’s the move from Hebrew to English (and back again). Yitzchak Blau continues this Tradition Online series offering his insider’s look into trends, ideas, and writings in the Israeli Religious Zionist world helping readers from the Anglo sphere to Alt+SHIFT and gain insight into worthwhile material available only in Hebrew.

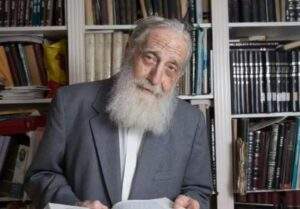

Prof. Shalom Rosenberg (1935-2023) z”l, who passed away two weeks ago, taught Jewish philosophy at Hebrew University and other educational institutions for many years, published numerous books and countless articles on Jewish thought, and was a public intellectual and an important voice in the Religious Zionist world. For years Rosenberg wrote a weekly column in the Makor Rishon newspaper [archived here], and a review of his most interesting essays is an excellent way to help understand his contribution to the intellectual atmosphere of our community (especially as so little of it has been made available in English). A smattering of examples indicates both the wide array of Jewish and gentile authors he works off and his keen insight.

Prof. Shalom Rosenberg (1935-2023) z”l, who passed away two weeks ago, taught Jewish philosophy at Hebrew University and other educational institutions for many years, published numerous books and countless articles on Jewish thought, and was a public intellectual and an important voice in the Religious Zionist world. For years Rosenberg wrote a weekly column in the Makor Rishon newspaper [archived here], and a review of his most interesting essays is an excellent way to help understand his contribution to the intellectual atmosphere of our community (especially as so little of it has been made available in English). A smattering of examples indicates both the wide array of Jewish and gentile authors he works off and his keen insight.

One piece discusses the wisdom of the common people. Indeed, in some Gemarot (Pesahim 66a, e.g.), the Sages determine halakhic practice based on observing the behavior of the masses. R. Kook emphasized this wisdom of the crowd in several contexts, even suggesting that when the learned sages do not make needed rulings, the correct approach can rise up from below.

Rosenberg distinguishes between R. Kook and a student of R. Shneur Zalman of Liadi, one R. Aharon Halevi Horowitz, regarding the public teaching of kabbala. What once was an esoteric wisdom has entered the realm of communal discourse. What generated this shift, causing wider exposure to the mystical teachings? Writing in the early 19th century, R. Aharon Halevi argues that the current generation is of such lowly stature that it will not understand the kabbala in any case and, therefore, no harm ensues. In contrast to that idea, R. Kook writes that our ability to teach kabbala to the masses stems from the enhanced status of contemporary generations. This reflects his overall orientation towards offering an optimistic evaluation of the broader public.

Another essay addresses the question of purity of motivation. In the ethical realm, Kant taught that ethics must be performed purely lishmah, for the sake of duty. If someone does an act of kindness to impress others or even out of sympathy, that act lacks ethical worth. A Jewish version of this was advanced by Yeshayahu Leibowitz who states that mitzvot should be performed purely as an act of worship and not to accomplish some other goal. Rosenberg notes how a Hasidic focus on interiority also highlights the centrality of correct motivation. Furthermore, the relentless drive toward self-perfection by the Musar movement often generated an attempt to stamp out any amount of self-interest.

Rosenberg writes that this striving for absolute purity leads to an absurdity. Having driven out all ulterior motives, will we not take some pride and joy in our accomplishment, thereby undermining the purity of motivation. Secondly, this approach leads to a preference for mechanical performance of mitzvot absent highly valued emotions such as love for others or enjoying Shabbat.

An innovative essay draws on a debate found in the Yerushalmi regarding egla arufa. The Torah outlines a ritual in which the elders declare that “our hands did not spill this blood” (Deuteronomy 21:7) upon the discovery of a deceased wayfarer in their city limits. According to Hazal, this means that “he” was not a guest that the community failed to take care of (Sota 45b). Who does the pronoun “he” refer to in the previous sentence? The Yerushalmi cites one opinion that it refers to the victim and another that it refers to the murderer (Sota 9:6). Rosenberg cleverly uses this to talk about a balanced approach to crime. On the one hand, we blame the evildoer and investigate if we did enough to prevent the suffering of the victim. On the other hand, we understand that the difficult situations society places people in (poverty, mental illness) often lead them to criminal activity. Utilizing this balance, we can simultaneously assign moral blame while realizing the necessity to change larger structural factors as a prophylactic against evil.

As a final example, Rosenberg addresses the extent of free will and mentions traditional positions that limit it. R. Dessler famously used military imagery to convey such limitations. For example, in World War I there was French territory, German territory, and a no man’s land the two countries fought over. So too, there is some spiritual territory we firmly hold—the realm of commitments and mitzva observance in which we are not tempted by transgression. On the other hand, some matters rest on the other side of the border, in “enemy” hands—mitzvot which we are not capable of fulfilling at the moment, for lack of resolve, motivation, or ability. The true “battle” of the spirit is won or lost on the middle ground, where our decision-making reigns and has consequence. Although the no man’s land shifts over time, on the other sides of its borders we do not have absolute freedom at any given moment.

R. Hasdai Crescas advances a more deterministic notion in which we totally lack freedom in the realm of action but have freedom in the arenas of emotions and attitudes. Having donated a lot of money to charity, I can either take great joy in that behavior or feel quite upset about it. To use another example, both Marx and Nietzsche stopped believing in God. Marx rejoiced in this while Nietzsche acknowledged the tragedy of the situation. Thus, a significant area of human freedom remains. Though R. Crescas does not represent a mainstream position, his view provides an option for contemporary Jews convinced by determinism.

I hope that this brief survey gives our English readers a sense of Shalom Rosenberg’s remarkable contribution to Jewish thought, and will motivate them to read his books and essays. See his TRADITION essay “Fate and Destiny” (Fall 2006), concerning Rabbi Soloveitchik’s “Kol Dodi Dofek.” We will be publishing an essay by Prof. Rosenberg, “A Narrow Bridge: Rabbi Nahman of Breslov’s Faith in a World of Doubt” in an upcoming issue.

Yitzchak Blau, Rosh Yeshivat Orayta in Jerusalem’s Old City, is an Associate Editor of TRADITION.