Alt+SHIFT: Aviezer Ravitzky

Alt+SHIFT is the keyboard shortcut allowing us quick transition between input languages on our keyboards—for many readers of TRADITION that’s the move from Hebrew to English (and back again). Yitzchak Blau continues this Tradition Online series offering his insider’s look into trends, ideas, and writings in the Israeli Religious Zionist world helping readers from the Anglo sphere to Alt+SHIFT and gain insight into worthwhile material available only in Hebrew. See the archive of all columns in this series.

Aviezer Ravitzky, Herut al ha-Luhot: Kolot Aherim shel ha-Mahashava ha-Datit (Am Oved, 1999), 368 pages

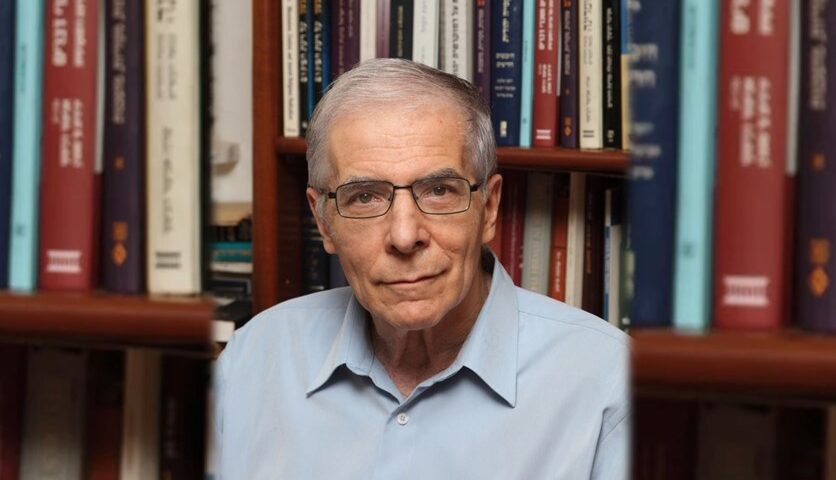

Prof. Aviezer Ravitzky

For many years, Prof. Aviezer Ravitzky (b. 1945) was a prominent Israeli public intellectual and a professor of Jewish Philosophy at Hebrew University. His most well-known book in English, Messianism, Zionism, and Jewish Religious Radicalism, explores the thought of Kookian Religious Zionists, Habad, mainstream Haredim, and the Neturei Karta. The community misses his moderate and insightful voice, of which we have been deprived since a 2006 accident, in which he was badly injured when hit by a bus, forcing him to leave the public stage.

Herut al ha-Luhot, as collection of ten essays, covers numerous topics germane to our current moment. I will not focus on the books more abstract subjects involving the thought of R. Soloveitchik or Prof. Yeshayahu Leibowitz, and instead focus on three chapters relevant to the debates between rival groups in the Jewish state. One essay on the proverbial “empty wagon” of secular Zionism contrasts the variety of tolerance exhibited by Hazon Ish with that of R. Reines, R. Soloveitchik, and Rav Kook. Hazon Ish found reason to neutralize negative halakhot about secularists but did not develop a positive vision of Jewish secularism. In his opinion, we ought not be harsh to hilonim in an era when God’s hand is not overtly manifest and when aggressive measures would prove counter-productive. He tended to relate to secularist individuals and not to a collective secular ideology.

Kook, by contrast, saw secular Zionism as adding a crucial component to the Jewish collective since the religious community has certain shortcomings (e.g., lack of vitality, focusing on details while losing the poetic vision) that require outside help. In one famous passage, he writes of the need to integrate the contributions of religion, nationalism, and liberalism (Orot, 79). R. Kook apparently viewed himself as someone standing outside the fray who could appreciate each group’s value. Ravitzky sharply notes a potential danger in R. Kook’s viewpoint. When one group contends that they have assimilated the truth of all the others, then that group runs the danger of becoming the most intolerant since it has already achieved completion, leaving no need to learn from others. Arguably, this has come to pass in the Hardal version of Kookian thought.

Another essay studies the relationship between religious and secular Jews in Israel. Let us begin with the optimistic aspects. Each side now understands that the other is here to stay and an entire spectrum of attitudes to religion lies between the two extremes. Jews in this middle could provide some kind of bridge between warring factions. Furthermore, few secularists want a Jewish state devoid of religious symbols and few Haredim truly want to implement “Medinat Halakha” (a state wholly managed by halakhic norms) immediately. Even some of the growing communal tensions reflect positive changes. When groups that formerly occupied the periphery (Revisionists, Haredim, Sefardim) move closer to the center of power, they naturally have more clout with which to generate conflict.

On the other hand, the existence of a continuum does not minimize the great and potentially dangerous gaps between the extremes. Furthermore, the divide may be particularly large in the cultural sphere. How much of a role does Jewish tradition play in the novels of Amos Oz and David Grossman (not much), and how much does the explosion of Torah literature exhibit real knowledge of broader cultural trends (even less)? This essay was written over a quarter-century ago, and it would be interesting to hear what a healthy Ravitzky today would say about R. Haim Sabato’s novels or Yishay Ribo’s music, both phenomena that postdate and complicate his analysis.

On the other hand, the existence of a continuum does not minimize the great and potentially dangerous gaps between the extremes. Furthermore, the divide may be particularly large in the cultural sphere. How much of a role does Jewish tradition play in the novels of Amos Oz and David Grossman (not much), and how much does the explosion of Torah literature exhibit real knowledge of broader cultural trends (even less)? This essay was written over a quarter-century ago, and it would be interesting to hear what a healthy Ravitzky today would say about R. Haim Sabato’s novels or Yishay Ribo’s music, both phenomena that postdate and complicate his analysis.

An article on tolerance raises important questions from a traditional Jewish perspective. While some sources fear excessive diversity of options (“Lest the Torah become two torot”), others celebrate debate. R. Yehiel Mikhel Epstein uses the image of harmony to convey the beauty emerging from disparate voices, and Netziv depicted the dangers of Migdal Bavel as a kind of totalitarian thought police. Furthermore, R. Haim ben Betzalel (brother of Maharal) objected to the codification process of Shulhan Arukh precisely because it reduced the variety of halakhic options.

What justifies tolerance even of evil or harmful opinions? Zealotry often comes with a price as it brings out the most aggressive traits of the zealots. Additionally, we may accept John Stuart Mill’s argument that truth only emerges when we allow all positions to compete in the marketplace of ideas. Maharal has a famous passage to this effect in his Be’er ha-Golah (#7). Finally, such tolerance may reflect our value of individual autonomy over coercion. Does Jewish tradition include sources that identify with this third factor? Ravitzky argues in the affirmative even as these sources do not quite call for the more robust self-legislation of contemporary liberalism.

I hope this brief taste gives our readers a sense of Ravitzky’s wisdom, and encourages them to sample his writing for themselves. While his voice has been silent and his pen still, his ability to bring classical Jewish thought to bear on contemporary Jewish life endures and continues to inform.

Yitzchak Blau, Rosh Yeshivat Orayta in Jerusalem’s Old City, is an Associate Editor of TRADITION.