A Chief Rabbinate That Might Have Been

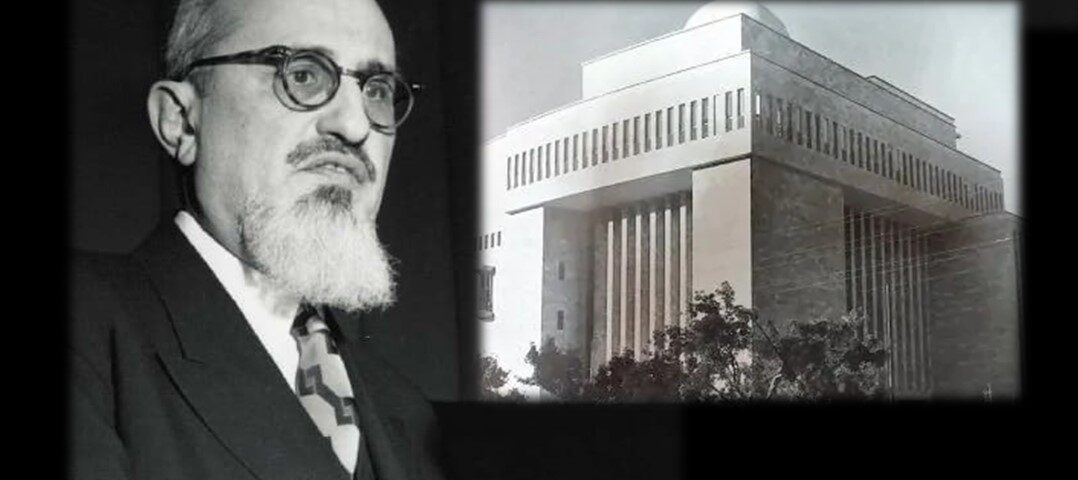

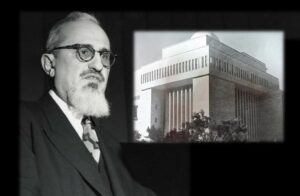

R. Soloveitchik gazes upon Heichal Shlomo, the seat of the Chief rabbinate.

Politicos interested in the interaction of religion and state have been captivated these last few weeks (in the way train wrecks draw our attention) by the twists and turns, and talks of deals and coalitions in the run-up to the long-delayed elections for the Israeli Chief Rabbinate. At the moment, for the first time the State of Israel has no Chief Rabbi, as the terms of the outgoing holders of that office expired on July 1. In fact, it’s the first double vacancy of Ashkenazi Chief Rabbi and Sefardi Rishon Lezion since the Chief rabbinate was established in 1921 (leaving the post of Head of the Beit Din HaGadol unmanned as well). Ongoing disputes and legal challenges to the appointment and makeup of the 150-member electoral council are the cause of the delay and vacancy. That those delays have been generated by an attempt to gerrymander who sits on that council to the benefit or detriment of certain candidates, the sense that the Religious Zionist community (the last sector to maintain any reverence for the Chief Rabbinate as an institution) are again likely to fail to secure the top spot for a representative of their community; and the whiffs of nepotism at play, all contribute to cynicism about an institution once headed by Rav Kook zt”l and other luminaries which should be a beacon lighting the way for engagement with Jewish life and values across all segments of the population. It is not yet clear how this byzantine process will play itself out, and what the outcome will be. Some hope while others fear that the longer the positions go unmanned the more likely it will be for more people to question whether we need a rabbi in the job at all (to say nothing of two rabbis). Others are mindful of the warning penned by S.Y. Agnon, “A city with no rabbi”—and certainly an entire State!—“Satan will appoint himself to the position as rabbi over the city, heaven forfend!”

But before we look ahead to how this might play itself out, there is value in looking backwards and revisiting the first time the State held such elections six decades ago, as that may tell us something about the contemporary scene. Upon the death of Rabbi Isaac Herzog in 1959 (he had been elected in 1937 during the British Mandate, and became the Chief Rabbi of Israel de facto upon establishment of the State in 1948), it was widely speculated that Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik would be a candidate. In the end, the position would remain vacant for almost five years, as the elections were delayed time and again over the absence of a consensus forming candidate, and—more significantly—that season’s own kettle of bitter debates which raged within the rabbinate and the government as to the electoral process. Although he initially considered the possibility, by February 1960, following a serious health scare and cancer surgery, the Rav decided that he would not be a candidate. The elections were nowhere in sight, and debate continued to rage over the composition of the electoral body (numbers of rabbis vs. “public representatives” made up of MKs, government ministers, local religious council heads, mayors, etc.). It also became apparent that although he enjoyed the crucial support of the National Religious Party head and interior minister Haim-Moshe Shapira, he could not count on the support of the whole party, which largely favored the candidacy of the eventual winner, Rabbi Isser Yehuda Unterman. Political machinations were in the works that would have limited Chief Rabbinate candidacy to those already in possession of Israeli citizenship (thus eliminating R. Soloveitchik), or candidates under the age of 70 (eliminating R. Unterman, in favor of Rabbi Shlomo Goren).

These moves, which did not succeed, were taken with Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion’s knowledge, and likely with his assent. The failed measures, widely viewed as attempts to rig the election, were put forth by Religious Affairs Minister Rabbi Yaakov Moshe Toledano, who was viewed as an instrument of Ben-Gurion. In an attempt to weaken the NRP and the influence the party tried to exert in passing “religious” legislation, Ben-Gurion openly favored R. Goren’s candidacy. Toledano’s efforts to block the election of R. Soloveitchik or Unterman must be understood against this background. The Rav’s vocal critiques against the politicization of the Israeli rabbinate had apparently ruffled feathers. Journalist Pinchas Peli blamed NRP Knesset members for scuttling R. Soloveitchik’s candidacy, claiming they feared his reputation for independence and that “he wouldn’t be a puppet in the hands of the party, malleable to its will.” In a letter to Shapira (who had been a childhood acquaintance), R. Soloveitchik stated he would not stand for election: “By nature I am a teacher. I know nothing of administering offices; I flee from ceremony, presentations and the press, and especially from politics. I had initially hoped to separate the spiritual ideals of this position and its technical and political needs. . . I had hoped that I could dedicate my time and energy to spreading Torah and knowledge of God—and I was ready to answer the call [for such a position]. . . However, developments in the situation and political complications in the recent past about the electoral process [convinced me otherwise]. . . Under such circumstances I do not see myself as a fit and proper candidate to be appointed to such a great position.” In a March 1960 interview with the Yiddish Der Tag Morgen Journal, he emphasized again that he was at heart a teacher, and that to be a rabbi means to be an educator, not a politician. Yet the interviewer asked a fair question: If it was no secret that the Chief Rabbinate was what it was, why did he entertain the idea for so many months, given that it seems so diametrically opposed to his nature and desires? R. Soloveitchik responded that three factors led to his considering the job nevertheless:

First, I thought that I could avoid the institutionalization and remain myself, I would be me and not the chief of rabbis. . . Second, in my great naiveté, I dreamed of being able to democratize the rabbinate in Israel [by freeing it from politics and the Religious Affairs Ministry]. Third, and this was the main attraction, was the potential for teaching and disseminating Torah. I dreamed that as Chief Rabbi, I would be able to transform the rabbinate into a font of Torah and knowledge. I thought that I would be able to deliver shiurim like I do in New York. . . The Chief Rabbi must be the leading teacher of Torah, otherwise in what way is he “chief”?”

In the end, R. Soloveitchik realized that these dreams were unattainable. This was brought about by a growing awareness of the insurmountable politicization. After numerous further delays, on March 15, 1964, R. Unterman was ultimately selected in a close election. Upon hearing of the elections, the Rav was reported to have quipped, “Now I can go to Israel for a visit without arousing suspicions that I am looking for a job!” As it happens, he never did visit Israel after that point (having only been once in 1935). It’s an interesting parlor game to consider what his impact might have been had he arrived in Jerusalem in the 1960s, and equally fascinating to speculate what his absence from the American scene from that point on would have meant for American Orthodoxy. Perhaps his vision for a Chief Rabbinate divorced from politics was naïve, as he said; more likely, it was an image of what the position might be, and the only scenario by which he could have envisioned himself functioning in it. In all cases, this chapter in R. Soloveitchik’s biography reminds us during this campaign season just how far we are from his vision of what a Chief Rabbi might be.

Jeffrey Saks is editor of TRADITION. This essay is adapted from “Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik and the Israeli Chief Rabbinate: Biographical Notes (1959-60),” B.D.D. 17 (2006).