Alt+SHIFT: Overweight

Yitzchak Blau returns for a special summer supplement to his popular Alt+SHIFT series—that’s the keyboard shortcut allowing us quick transition between input languages on our keyboards. For many readers of TRADITION that’s the move from Hebrew to English (and back again). R. Blau offers his insider’s look into trends, ideas, and writings in the Israeli Religious Zionist world helping readers from the Anglo sphere to Alt+SHIFT and gain insight into worthwhile material available only in Hebrew. See the archive of all past columns in this series

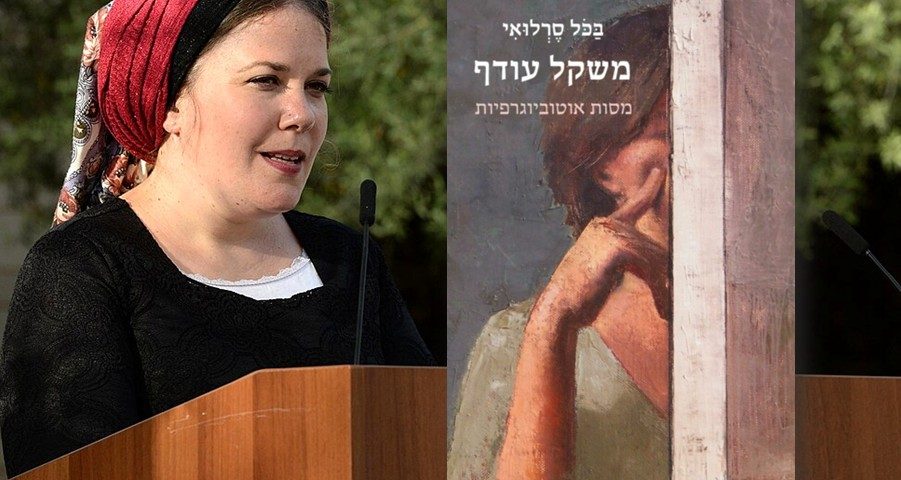

Bacol Serlui, Mishkal Odef: Masot Autobiografiyot (Dvir, 2024), 208 pp.

Bacol Serlui, Mishkal Odef: Masot Autobiografiyot (Dvir, 2024), 208 pp.

Do not be misled by the title; Bacol Serlui’s collection of autobiographical essays. Mishkal Odef (in English it would be called Overweight), is a wide-ranging personal account touching on much more than weight struggles. Topics include the author’s religious journey, female patients and male doctors, the menstrual cycle, contemporary discourse about tzeniut, growing up as the child of divorced parents, and balancing time between domestic responsibilities with professional writing. Serlui, a poet, teacher, and contributor to the Makor Rishon newspaper, offers insight into a variety of fields.

[Read Bacol Serlui’s “Psalms for a State of Vertigo” in TRADITION (Winter 2024), penned as a response to the early days following October 7th.]

Her difficulties with weight lead to a critique of the model of the perfect women generated by western media. She refers to a “religion of thinness” with its primordial sin of eating. At the same time that feminism has increased women’s voices and impact, women are more subject to needing to achieve a certain look, and she puts her finger on this painful irony. Women would like to have soft, wrinkle-free skin but the time when they have such things, adolescence, is precisely the greatest time of their concern about body image.

One of the book’s saddest sections describes Serlui’s experience in Horev high school. This school achieves among the highest exam scores in the country year after year and yet academic achievement and other talents (volunteering for MDA, serving as youth group counselors) apparently do not give the girls a sufficient sense of self. Eating disorders are common and all students worry too much about their figures.

Serlui conveys some powerful thoughts regarding tzeniut. She worries about the fine line driving concerns about female modesty and fear of women. Extreme concern for tzeniut, such as not allowing women’s pictures in newspapers or women being forced to the rear of the bus, actually parallels pornography in that both erase other aspects of female personhood and see women as purely sexual beings.

In this context, Serlui makes a very sharp observation about the Haredi community. Isolationism provides certain advantages in maintaining communal values. On the other hand, “this closure (segirut) dulls the senses. When there is no dialogue with the outside, there are no external tools for evaluation and self-reflection.” Sometimes, an outsider’s perspective helps us understand our own community’s shortcomings.

Life’s complexity and conflicting emotions emerge clearly. The same person who sees value in enforced monthly halakhic separation between husband and wife, leading to a focus on non-physical aspects of a relationship, also feels frustrated by the inability to touch. Serlui was upset for years about Eikha’s comparison of sinning Israel to a nidda; is a women menstruating somehow sinful? She came to an understanding that the parallel indicates how both conditions are reversible; a woman becomes permissible to her husband and sin can be overcome.

One interesting chapter details her negative experience with male doctors when she has an enflamed cyst. They do not take her pain seriously, and offer a misdiagnosis despite her insistence that they have gotten it all wrong. Indeed, scientific studies indicate that doctors give more credence to male pain than female pain.

I particularly liked the first section of the book which outlines the author’s religious upbringing. She grew up in the right-of-center Merkaz HaRav orbit (her father wanted her to go to attend the Tzviya high school but her mother won) and her parent’s divorce was considered somewhat scandalous at the time. Serlui describes the worldview in which she was raised as one in which everything is perfectly clear and which inspires confidence in one’s religious path. However, she came to the conclusion that life is more complex and suggests that being a child of divorce helped her realize that there are usually two sides to a story.

One dissonance struck her profoundly. The world she grew up in talks a great deal about love for every Jew. Its rabbinic hero, R. Avraham Yitzhak Hakohen Kook, found virtues among the secularists. He famously said that “the truly righteous do not complain about evil; they add righteousness.” Yet this did not mirror how the Merkaz world spoke about left-wing Jews they disagreed with in Israel’s contentious 1990s and early 2000s (leading up to the Gaza disengagement). They saw no truth or idealism in the other side. The gap between abstract profession of love and actual enmity towards other Jews was partially why she sought a different religious community.

Another factor was the place of women in her society. She wanted to study Gemara and dance with a Sefer Torah but was barred from doing so. Serlui accurately notes how women’s motivations are frequently questioned whereas men’s are not. This too motivated a religious quest although her love of Torah and Hashem kept her in the Orthodox world.

This brief summary does not cover all the important topics in Bacol Serlui’s book. Go and read it, it’s worth its weight.

Yitzchak Blau, Rosh Yeshivat Orayta in Jerusalem’s Old City, is an Associate Editor of TRADITION.