REVIEW: The Women of Toldot Aharon

Sima Zalcberg-Block, Hen Adayin Yoshvot veTofrot: MeOlamon shel Neshot Hasidut Toldot Aharon (Bialik Institute, 2024), 388 pp.

Sima Zalcberg-Block, Hen Adayin Yoshvot veTofrot: MeOlamon shel Neshot Hasidut Toldot Aharon (Bialik Institute, 2024), 388 pp.

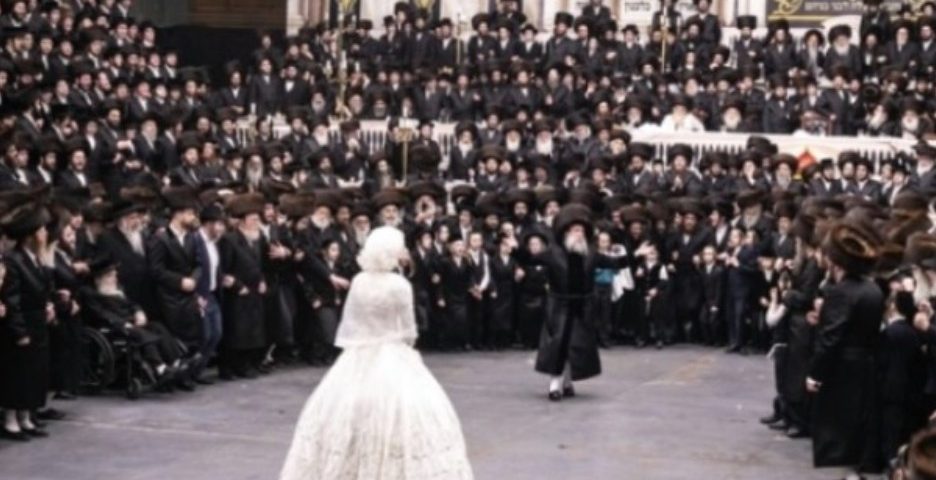

Sima Zalcberg-Block’s new Hebrew anthropological study, whose title would be rendered in English as They Are Still Sitting and Sewing: The Toldot Aharon Hasidic Women, offers a rare and revealing look into a Hasidic community in Israel. Toldot Aharon is one of the most closed and zealous sects within the Haredi world. The book is a remarkable achievement not only because its author gained access to this secluded religious group but because it brings forth the voices of its women, whose experiences have been largely absent from scholarly literature. The author’s ability to build trust and conduct long-term fieldwork in this environment marks a major methodological and ethnographic accomplishment.

Toldot Aharon is a “minority within a minority” in Israeli society—Haredi, anti-Zionist, and staunchly resistant to modernity. Within this group, women are further sequestered by strict gender roles, creating a “minority within a minority within a minority.” Their lives are centered on domestic duties, religious observance, and work within the home, making them virtually invisible to outsiders and to researchers. Previous studies of Haredi society, often led by male scholars, have focused on men’s experiences or generalized depictions of “Haredi women” as a homogenous, passive group. The author sets out to dismantle this stereotype through detailed ethnographic engagement.

The project began unexpectedly in 1996 during a taxi ride, when a conversation with a Belz Hasidic woman about women’s work outside the home in Haredi society led to a remark about Toldot Aharon women, who “sit at home and sew.” Intrigued, the author shifted her research focus toward them. When she presented the idea to Professor Menachem Friedman, her Ph.D. advisor, he asked pointedly, “How will you enter it?”—a question that captured the enormity of the challenge. Toldot Aharon’s insularity, combined with the restrictions on contact between men and women, had long discouraged in-depth research on its female members. In this, the author’s gender proved to be a key advantage, allowing her access to female spaces and daily routines. Over time, she was able to build relationships of trust and observe life inside homes and informal gatherings. This close engagement made it possible to document her subjects’ experiences in a way respects their worldview yet avoids romanticization. The ethnography captures their voices, gestures, and social interactions, revealing a textured reality that contrasts sharply with earlier portrayals of Haredi women as silent or voiceless.

In this account, the women of Toldot Aharon emerge as active participants in the preservation and transmission of their community’s religious ideals. While they inhabit clearly defined domestic roles, their work and interactions form part of complex networks of support, mutual obligation, and meaning-making. The sewing metaphor—rooted in the remark that first drew the author to the topic—becomes symbolic of how these women weave together religious values, family responsibilities, and group identity.

A central theoretical insight in the book is the role of gender as a marker of group identity. Drawing on Baer, Vance, and Weber, the author shows that the way a religious group defines women’s roles is deeply tied to how it defines itself in relation to surrounding society. For Toldot Aharon, preserving strict gender boundaries functions not only to maintain internal order but to signal ideological separation from both secular Israeli culture and less stringent Haredi factions. The women’s lives are therefore not merely private or domestic, they serve as visible symbols of the group’s commitment to religious purity and social isolation.

The book also situates the women of Toldot Aharon within the broader transformations occurring in Haredi society during the research period. In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, many Haredi communities were experiencing a process of “Israelization,” with increased economic integration and exposure to mainstream culture. Haredi women in more moderate groups were entering the workforce in growing numbers, adapting to economic and social pressures—namely in order to support their families, whose fathers and husbands have committed themselves to full-time Torah study. Toldot Aharon, however, maintained an isolationist stance, with its women largely remaining in home-based or community-centered roles. This tension between adaptation and resistance highlights the group’s determination to preserve its way of life in the face of societal change or economic pressure.

[See the table of contents and read an excerpt from Hen Adayin Yoshvot veTofrot.]

The study is notable for its methodological achievement. Gaining entry into such a guarded community requires years of persistence and cultural sensitivity. Once inside, the author, a lecturer at Ariel University’s School of Social Work, was careful not to impose external judgments but instead to interpret the women’s actions and beliefs within their own cultural logic. This approach aligns with feminist anthropology’s commitment to amplifying marginalized voices on their own terms. The work also demonstrates that access is not simply a matter of physical entrée but of negotiating trust, reciprocity, and shared understanding over time.

By focusing on one of the most extreme and secluded Hasidic courts, the book fills a significant gap in the literature on Haredi women. While recent scholarship has expanded our knowledge of women in mainstream Haredi groups, there has been little sustained attention to the lives of women in most isolationist factions. The detailed observations here offer both a corrective to oversimplified portrayals and a foundation for comparative studies across different Haredi subgroups. This is manifested in the book’s main chapters: The women’s education and exposure to general knowledge; their apparel and appearance in public; the match-making process; and “cracks in the wall,” namely women who leave the group.

The narrative also challenges the tendency to interpret traditional gender roles solely as mechanisms of oppression. While the author does not ignore the constraints these women face, she reveals how they also find meaning, purpose, and even influence within the boundaries set for them. Their agency may be exercised in subtle and culturally specific ways: through managing household economies, raising children according to the group’s values, or sustaining the social fabric of the community. These forms of action, often invisible to outsiders, are critical to the survival of Toldot Aharon’s distinct identity.

One of the book’s strengths is its historical sensibility. By contextualizing the lives of these women within larger shifts in Israeli society, the author shows that even the most insular communities are not static. Globalization, technology, and economic change exert pressures that must be managed, even if the group’s public stance is one of total separation. The women’s strategies for navigating these pressures, whether by reinforcing boundaries or adapting discreetly, offer a lens into the community’s broader survival strategies.

In terms of scholarly contribution, the book resonates beyond the field of Haredi studies. It offers insights relevant to anthropology of religion, sociology of minority groups, and gender studies. It also provides a methodological model for conducting respectful, in-depth research in closed societies, demonstrating how patience and reflexivity can open doors that at first seem permanently shut.

Ultimately, the book is both a window into a hidden world and a mirror reflecting the ways in which gender, tradition, and ideology shape the lives of women in conservative religious settings. It neither idealizes nor condemns, but instead presents a layered, empathetic portrait grounded in careful observation and analysis. The result is a work that deepens our understanding of both the particular community it studies and the broader dynamics of cultural preservation in the modern world.

This is an important and original contribution to the anthropology of Haredi Judaism. By illuminating the experiences of the women of Toldot Aharon, it enriches our knowledge of how religious communities maintain their identities under pressure, how women operate within—and sometimes subtly reshape—patriarchal systems, and how ethnography can bridge the gap between outsider curiosity and insider reality. It will be of lasting value to scholars, and anyone interested in the intersection of religion, gender, and cultural continuity.

Menachem Keren-Kratz, an independent scholar, completed doctorates in both Yiddish Literature and Jewish History. His most recent book, Jewish Hungarian Orthodoxy: Piety and Zealotry (Routledge), was reviewed in our Summer 2025 issue.