RESPONSE: Anti-Aging & Resurrection

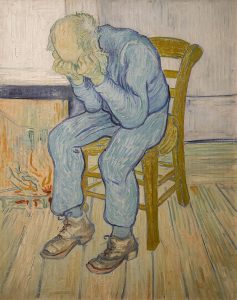

Van Gogh, “At Eternity’s Gate” (1890)

Recently in TRADITION, Rabbi Jason Weiner offered an interesting and wide-ranging survey of issues relating to medical anti-aging interventions and generative A.I. chatbots in his article “A Jewish Approach to Anti-Aging Interventions” (Summer 2025). I wish to applaud this article, and also to add an additional relevant argument or two, based on the teachings of Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik.

At one point, relating to concerns about overpopulation in the event of significantly longer lifespans, Weiner notes the novel approach of the Divrei Yatziv to Yoreh Deah 110, that in the messianic period, in which there is no death, there is also no obligation to procreate. He notes that this view is relevant “[t]o those who see these anti-aging medical advancements as being messianic breakthroughs” (71), without entering the question of who views scientific steps to significantly lengthen life expectancy as messianic, or even whether we should view it that way.

In light of teachings of the Rav that have recently come to light—published in the pages of TRADITION!—we can begin to respond to that question, while also touching upon some of the larger issues that Weiner was treating.

In the article “Resurrecting Rabbi Soloveitchik’s Approach to Tehiyyat ha-Metim” (Spring 2023), I reconstructed the Rav’s views on resurrection out of fragmentary notes on a 1948–49 Revel course taken by a 21-year-old not-yet-Rabbi Norman Lamm.

R. Soloveitchik argues, based on the content of the second blessing of the Amida, that the messianic era resurrection of the dead should not be seen as a supernatural event, but rather as part of the natural order created by God, just like all other life-sustaining capacities of the world discussed in that blessing.

As for the purpose of resurrection, which is important enough to be considered one of the thirteen principles of faith, R. Soloveitchik’s view is summarized as follows:

For R. Soloveitchik, the goal of tehiyyat ha-metim is to eradicate the suffering inherent in death. Just as God saved Hannah from her suffering by having her bear a child, Samuel, thus being cured of her barrenness, God is committed to cure every ailment. Eschatology, our belief in the end of days, is the “full realization of [the] ethical norm” of perfecting nature. That messianic hope is the point of tehiyyat ha-metim, in an ethical rehabilitation of reality, yet still a reality continuous with this one, in which the world works as it did before (olam ke-minhago noheg), and in which nature is still imperfect, albeit improved….

On R. Soloveitchik’s view, the eschatological era, including the resurrection of the dead, is part of an asymptotic process of continually perfecting God’s physical world. It is not a fundamentally different world without the physical challenges we face today, but at least the scourge of death and attendant suffering has been cured (202-203).

Although this particular view on resurrection only appears in a student’s lecture notes, it is very much consistent with R. Soloveitchik’s writings about the valuation of life over death in Halakhic Man, and a partial naturalism with regard to miracles in Emergence of Ethical Man.

One question that is not explicitly addressed in the lecture, at least as far as is accessible, is whether a divine miracle is necessary to achieve this ideal world, or whether scientific advances to undo death would qualify for the resurrection that is the topic of this ikkar emuna. In light of both a close reading of Emergence of Ethical Man and some points in this lecture, I argued that we should see miracles as essential to the Rav’s account (see 210–212).

But that question might be tangential to the larger point. Even if the use of technology to lengthen life significantly does not qualify as tehiyyat hametim, it still would advance the goals of that principle of faith and thereby serve as a value that should be pursued.

Thus, leaving aside the question as to whether R. Soloveitchik’s view would deem anti-aging medical advancements to qualify “as being messianic breakthroughs” absent a clear divine miracle, there is a broader point being made by the Rav that is relevant to questions of prolonging life—namely, the imperative to alleviate suffering and to eliminate death. Although one could imagine science allowing people to live longer lives but still suffering illness in equal measure (perhaps drawn out over even greater spans of time), presumably solutions to the negative effects of aging will also allay human suffering in significant measure. And the longer one lives, the more one has “the opportunity to create, act, accomplish,” which is why “halakhic man prefers the real world to a transcendent existence” (Halakhic Man, 32). As R. Soloveitchik argued in that lecture, this moral basis is the core idea behind the principle of tehiyyat ha-metim.

This principle is ethical and anthropocentric in nature: that God will remove death and suffering and thereby improve the world, and we humans are expected to emulate God’s ethical actions in trying to minimize suffering ourselves, and, it would follow, to work to prolong life expectancy, as well. Along similar lines, in his essay “A Halakhic Approach to Suffering,” appearing in Out of the Whirlwind: Essays on Mourning, Suffering and the Human Condition (Ktav, 2003), R. Soloveitchik describes the human obligation to overcome suffering, through science.

Thus, for R. Soloveitchik, prolonging human life serves to emulate God in an all-important moral endeavor. We pray for the day that God defeats death entirely, in which case we can certainly discuss the Divrei Yatziv, although we might also propose applying his argument in pre-messianic times. Even if we only merit to see a stop on the way to a full, divinely coordinated tehiyyat ha-metim, the Rav’s view means that we should appreciate the lengthening of human life by medical intervention as a proto-messianic moment, as well. This approach of R. Soloveichik thus offers an additional theological reason for continuing to pursue such advances.

Rabbi Dr. Shlomo Zuckier, consulting editor at TRADITION, is the Kaplan Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Toronto.