Sparks of Hidden Light and the Daf of Life

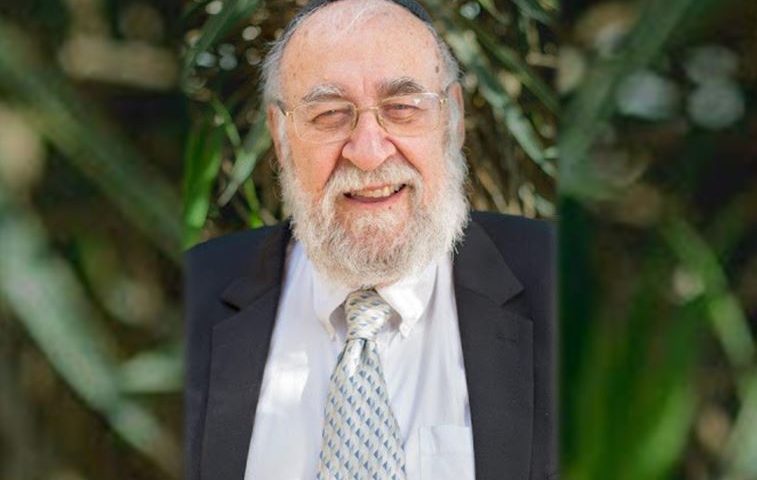

Remembering Rabbi David Ebner zt”l

Remembering Rabbi David Ebner zt”l

Words can scarcely contain the life of Rabbi David Ebner, who left this world suddenly this week at the age of 80. He was at once a rebbe and a poet, a scholar and a seeker, a mentor, confidant, and friend to thousands of students across the world.

He did not like exaggeration in his lifetime, and so now, even after his passing, I will not offer grand words of eulogy. Rabbi David Ebner zt”l preferred things as they were: a Daf of Gemara studied carefully, a niggun sung with eyes closed, the power of words turned into poems, and the light that radiated from the paintings of Rembrandt, Pissarro, and Monet. He studied and taught Torah, Hasidut, poetry, and Kant with the same seriousness and joy. He taught us not only Torah but also how to laugh, how to stumble, how to search.

A Life in Torah and Teaching

Born in Bradford, Pennsylvania, in 1945, R. Ebner received semikha at Yeshiva University, where he studied under Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik, along with other renowned rabbinic teachers and scholars, and earned a Ph.D. in Talmud from YU. He began his career as an academic and educator in America, teaching sociology and working with the Institute for Jewish Life of the United Jewish Communities.

In 1982, he and his family made aliya, where his true calling emerged most fully: guiding generations of students in Israel. For more than two decades, R. Ebner was one of the spiritual pillars of Yeshivat HaMivtar in Jerusalem and Efrat, serving as Mashgiah Ruhani alongside his dear friend and partner R. Chaim Brovender. Later, at Yeshivat Eretz HaTzvi in Jerusalem, which he helped found, he continued as a Rosh Yeshiva and spiritual guide.

For those who did not know him, “guidance” could sound abstract. In truth, he was the anchor of his students’ spiritual acclimation to studying and living in Israel — the one who bridged the gap between the Torah of the Diaspora and the Torah of the Land. He also mentored young Jewish educators through ATID and sustained weekly havrutot with scores of former students, shaping voices that would go on to influence classrooms and communities across the world.

But to speak only in terms of institutions misses the essence. For his students, he was the rebbe who taught not just how to learn a Daf of Gemara, but how to live what we came to call the “Daf of Life.”

The Daf of Life

At Yeshivat HaMivtar, R. Ebner taught shiur aleph — the entry-level Talmud class. Many of us came from strong academic backgrounds, but he insisted that past accomplishments meant little here. We had to start at the beginning: word by word, phrase by phrase, learning not only how to read a Daf, but how to navigate the pages of life. He tried to teach us how to think — and often, how to laugh at ourselves along the way. Each class was more than an intellectual exercise; it became a guide for living with honesty, humility, courage, and a generous measure of humor.

And he often returned to Avraham Avinu. The Torah tells us almost nothing about Avraham’s life before God chose him. Why the silence? Because, R. Ebner explained, each of us must write our own Torah, our own commentary, in order to find God personally and authentically.

He reminded us constantly that the secret of study was not to imitate others, but to confront our own doubts and gifts without embellishment or excuse. Though he carried his own struggles, I never once heard him complain. He turned attention away from himself and toward us. His wit carried wisdom, his humility was genuine, and his humor — sharp, pointed, and always with a hidden message — stayed with us long after the class was over.

And he was more than a teacher. He was a confidant. Many of us sat with him for hours, pouring out our struggles, questions, and private fears. He listened deeply, never rushed, and he carried our secrets with a fidelity that made us feel utterly safe. That trust bound us to him as much as his Torah did.

[Read R. David Ebner’s 1992 contribution to TRADITION’s “Divided and Distinguished Worlds” symposium.]

R. Ebner with the author (Moscow, 2013)

Humor and Humanity

R. Ebner’s long friendship with R. Brovender (יבלחט”א), another legendary educator, was a model of humility and good humor. Both men took Torah seriously but were careful never to take themselves too seriously. They walked with the giants of Jewish thought and the leaders of Jewish education, but — in the words of Rudyard Kipling — they always kept “the common touch.” That balance — seriousness with lightness, stature with humility — was one of R. Ebner’s great gifts.

He brought that same humor to unexpected places. At my son’s bar mitzva in Moscow, which fell during Hanukkah, he stood lighting the menora beside a Russian New Year’s tree. The photograph from that evening captures him perfectly: rooted in Torah, yet with a sparkle of humor that could make even such an unlikely juxtaposition feel natural, even joyful.

Music, Dance & Beauty

If Torah was his foundation, poetry, niggunim, and dance were his expression. He loved the words and lessons of Hasidut — “Rozenson, we are learning the Sfas Emes for inspiration,” he would remind me during our Friday morning havrutot: he in his Jerusalem home, surrounded by thousands of sefarim, and I in my Moscow office at the time, lined with Russian-language books and marked by the challenge of trying to help revive Jewish life in a country bereft of anything Jewish for decades. Those conversations — spanning time zones, languages, and histories — captured what R. Ebner so often did: he built bridges between worlds, showing how Torah could reach across distance and circumstance to touch us, and through us, the work we were trying to do and our lives directly.

And he loved niggunim — those wordless Hasidic melodies that carried him and us closer to God. At weddings, his feet would come together the way angels are described in Isaiah, and then he would whirl with such radiant joy that we felt lifted into his circle, as though nothing else in the world existed but the dance.

He also loved beauty. Not as decoration, but as a doorway into something greater. He hung Pissarro’s Sunset at Éragny near his bed and cherished Monet’s Water Lilies at the Met. He would often tell the story of Rav Kook, who once said that Rembrandt’s paintings reflected the hidden light of creation — the first light that God set aside for the righteous. Without exaggeration, and he hated exaggeration, I can say that R. Ebner allowed his students to glimpse a spark of that hidden light.

A Voice in Poetry

Later in his life, R. Ebner turned more consciously to poetry. He published three collections — The Library of Everything, Perhaps This Poem, and Dance Words. His poems were spare and searching, filled with the same blend of faith and honesty that marked his teaching. In one poem, he wrote that “perhaps this poem / is a bridge across the silence.”

For us, that line was no abstraction. His life itself was such a bridge — from text to soul, from Jerusalem to Moscow, from the beit midrash to the wider world. Just as our havrutot once stretched across continents, his poetry reached across silence, offering us a way forward when words felt insufficient.

The Last Song

On the morning of his passing, I hurried to Hadassah Hospital, where his children stood at his bedside. It was clear his body could no longer bear the pain. We cried, held his hands, and began to sing a niggun. In my mind it was Aheinu kol beit Yisrael — “Our brothers, the whole house of Israel.” It was the melody he had so often sung in yeshiva, eyes closed, heart open.

As we sang, his soul ascended. In that moment, I could hear again the voice with which he would lead us in prayer on Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur — strong, confident, not for himself but for the One above and for us below. A voice raised to Heaven on our behalf.

His Legacy

R. David Ebner cannot be reduced to titles or dates. His legacy rests in the way he taught us to live Torah with honesty and joy, in the trust he inspired as a confidant, and in the bridges he built — across generations, across distance, across silence. For those who knew him, his absence is immeasurable; for the Jewish people, his life is a reminder of the kind of teacher we most need.

In the words he so often cited by the poet Dylan Thomas:

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

R. Ebner did not rage. He searched, he taught, he sang, he danced, he wrote. And in so doing, he became a bridge for us — helping us glimpse, if only for a moment, that hidden light: “For with You is the source of life; through Your light may we see light” (Psalms 36:10).

Dr. David Rozenson is executive director of Beit Avi Chai in Jerusalem.