REVIEW: The Most Reluctant Convert

The Most Reluctant Convert: The Untold Story of C.S. Lewis, a film written and directed by Norman Stone (1A Productions & Fellowship for Performing Arts, 2021)

This past October marked the 75th publication anniversary of the first installment in C.S. Lewis’ Narnia series, The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe. Lewis’ former housekeeper Jill Freud (she was married to the famous psychoanalyst’s grandson), said to have been the inspiration for the character of Lucy in that landmark of children’s literature, died even more recently, this past November 24. All of which perhaps gives plausible license for offering some thoughts now, several years after its 2021 release, on a thought-provoking movie about Lewis, The Most Reluctant Convert (the movie is available from various streaming services).

This past October marked the 75th publication anniversary of the first installment in C.S. Lewis’ Narnia series, The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe. Lewis’ former housekeeper Jill Freud (she was married to the famous psychoanalyst’s grandson), said to have been the inspiration for the character of Lucy in that landmark of children’s literature, died even more recently, this past November 24. All of which perhaps gives plausible license for offering some thoughts now, several years after its 2021 release, on a thought-provoking movie about Lewis, The Most Reluctant Convert (the movie is available from various streaming services).

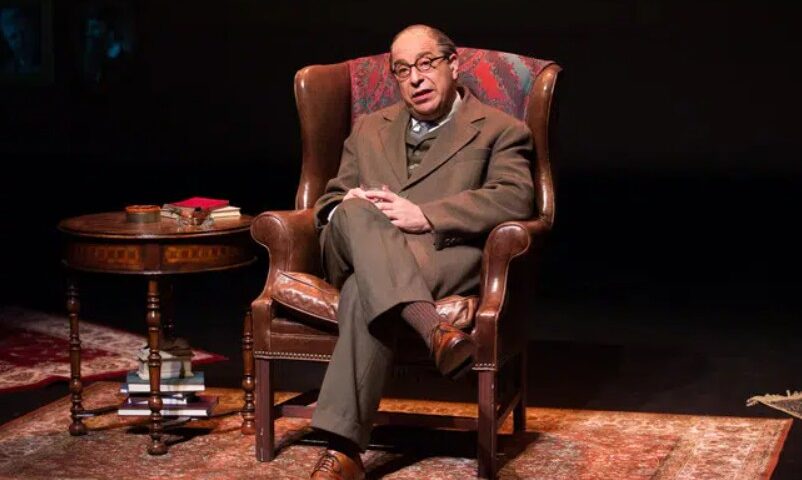

The movie traces the evolution of Lewis, from his early determined atheism, through a period of uncertainty and religious experimentation, to his ultimate “conversion” into a believing (Anglican) Christian. Told exclusively from the protagonist’s voice, we follow both a younger and older version of Lewis, mostly as he walks in and around the leafy Oxford campus where he lived as a Fellow. I found the movie to have successfully adapted from its original incarnation as a stage production, the production company having also previously produced a stage version of another Lewis classic, The Screwtape Letters. (Readers will recall the recent discovery of a letter similar to the epistles featured in Screwtape, published in TRADITION as The Asmodeus Letters [Spring 2022]).

Jewish viewers may wonder if there is what to be gained from watching such a movie. While Lewis greatly respected Judaism, he was, after all, an exponent of Christianity, and quite naturally preferred his own acquired religion to ours (on these points, see Mark Gottlieb’s recent “C.S. Lewis and the Jews” [TRADITION, Summer 2025]). Indeed, in the movie (all of which is based strictly upon Lewis’s memoirs and writings) an evolving Lewis muses over a number of the world’s great religions, and asserts, “All that is best in Judaism and Platonism survives in Christianity.” One might conclude then that the movie, quite literally, preaches only to the converted. However, after watching and reviewing this tight 70-minute film, I came away with much to reflect upon.

One point that impressed itself upon me—a point which, I think, behooves us to remind ourselves periodically—is just how vastly different we are from the “Goyim” around us. I don’t mean so much the tenets of our religion, but in the existence of religion itself. Observant Jews are fairly saturated with religion. It is an enormous part of our life, from the moment we awake, till we close our eyes at night. Yet as the movie makes clear, even in the Edwardian Era of Lewis’s Belfast youth, a period sometimes imagined as one of rigid religiosity and upright Anglican churchmen, huge numbers of men simply didn’t believe in religion at all. They felt there either was no God at all, that He was simply indifferent, or worse, that far from being beneficent, He was actually malevolent. (Lewis felt this last possibility could not logically be supported, and thus, in his early period, fit more in the category of simple atheist.)

In our times, though some have sensed the beginnings of a religious reawakening afoot, we are still in a highly secular environment. For much of the world, God is barely existent, if at all. We should not imagine things like Christmas trees or crucifix jewelry to be anything more than the trappings that they are. The Most Reluctant Convert does much to drive this point home.

With that, the beginnings of Lewis’ transformation makes for a fascinating comparison to our own Jewish world. Following his brother, Lewis was sent at the age of 15 to a private tutor named William Kirkpatrick, with whom he lived and studied between 1914–1917. Here he would learn the Greek and Roman classics, as well as more modern writers such as Voltaire and Faust. Every statement of Lewis was challenged by Kirkpatrick, who would seek to expose any faulty premise upon which the statement was unwittingly premised. The two would go for long walks in the forests, discussing and analyzing and simply enjoying the quiet. I could not help but smile at these idyllic scenes, recalled so fondly by Lewis throughout the movie—for here was the Rebbe-Talmid relationship as it was meant to me! One-on-One, where the disciple was with his master not just for an hour or so in the morning, but all the day long. Lewis was fortunate to have been educated in such a system.

I also found it interesting to see how Lewis’ first forays into the world of the spirit focused not precisely on religion, but on its shadow world—that of the occult, with its circles and pentagrams, Ouija boards and séances. The fact that such matters were scorned by both the religious and the rationalists alike appealed, in Lewis’ words, “to the rebel” in him. Those of us familiar with searching individuals might detect a similar strain within our own uniquely Jewish ecosystem.

But the similarities to our own world end here, and nowhere is this more evident than in Lewis’ first tentative steps to full-blown acceptance of a new faith. Lewis’ struggle centered entirely around the world of ideas. It was not prompted by any single emotional event (what a Christian might call a “Damascus Road” experience), but by pure and simple rational thought. He wrestled mightily with the concept of materialism, which dominated much of 19th and 20th century philosophy. According to this theory, all of human behavior could be reduced to chemical reactions, or as Lewis phrases it, “atoms colliding in the brain.” Notions of individual personality, and certainly any idea that there might be within us a spark of the divine, were all said to be illusory. Lewis thought deeply on this topic, probing it and testing it, and it was not until he at last rejected it that he truly began his journey to Christianity.

By great contrast, in the process experienced by so many of our ba’alei teshuva brothers and sisters, the odyssey seems to be all about action. Acceptance of the Sabbath, laws of family purity, kashrut, and so forth. Is there even a philosophical inquiry at all? Should there be?

Moreover, I have often heard that it’s the cholent that spurs more ba’alei teshuva on their path than anything else. That is, emotion is the driver (often experienced as a guest around a Shabbos table) rather than rationalism. It caused me to wonder: What really should be the motivating factor? Is there a preferred approach, as it were, to how one should advance towards God?

One method might look towards the great, gleaming Golden Mean as a beacon. In this conception, the searching Jew would have a perfectly synthesized mind and heart, such that both would put their combined weight together in prompting one to change one’s life. Life doesn’t seem to work like this, however. Perhaps collectively, some impossible analysis might show equal numbers of people motivated as much by one as the other. As individuals, however, clearly our very nature dictates what will have the most effect upon us. Lewis, at any rate—and this is the whole point of the movie—was moved more by his intellect than his emotion. It was only because his mind forced him to move, however reluctantly, in the direction of religion, that he allowed himself to begin forging a new pathway in life.

What I thought perhaps most interesting of all, though, was the last stage in his journey. By his mid-20s Lewis had rejected his earlier atheism and was now convinced that there had to be higher power. But locating that within Christianity was a different matter altogether. He now had to face the thorny, until-now-rejected question of whether a man, of flesh and blood, could be a deity. Unless and until he accepted this proposition, Lewis might have advanced in his appreciation for religion, but he would not have actually converted.

Indeed, in that regard, the inclusion of the word Convert in the movie’s title provides yet another distinction between our two religious faiths. For, of course, Lewis was already Christian even before his “conversion.” They use the term—as Evangelicals do with the phrase “born again”—in the sense of a transformative experience, of becoming a believer. The distinction we draw, between a ger and a ba’al teshuva, seems foreign to the Christian experience.

And the challenge Lewis was confronted with was a fundamental one. As the movie makes clear, there was to be no “compromise” measure, of accepting Jesus as a great teacher of morality, without accepting him as divine. In a discussion with his Oxford peers (among whom was counted J.R.R. Tolkien), the point is put fine: If Jesus’s claims were not all true, then he was a fraud. To refer to him as merely a wise teacher was “patronizing nonsense.” That was not an “option” available for those who would profess Christianity, nor was it ever intended to be. This was the last hurdle encountered by Lewis, and I confess, I was eager to learn how he cleared it.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, given the appearance of this article in TRADITION, a Journal of Orthodox Jewish Thought, I found the arguments unconvincing. In essence, Lewis reasoned, it would have been lunacy for a man to have made claims of divinity, and none of his interlocutors ever thought Jesus mad. Moreover, if it was false, it was the type of claim only a megalomaniac would make, hardly something one would expect from the pacifist and meek personage Jesus was reported to be. Of course, these arguments focus only on Jesus himself, and not on what his followers might have done. And while granted the movie is only a synopsis of Lewis’ brilliant career and spiritual journey, and he explored these arguments more fully in his writings (see especially the concluding chapters of his autobiography, Surprised By Joy, which offers much of the best material that made it into the screenplay). Still, it appears that it was chiefly upon these slender reeds that Lewis made the leap to become, ultimately, the great apologist of what he famously called “Mere Christianity.” I did not feel the movie properly addressed this final stage—not necessarily a fatal flaw for me, but perhaps of crucial concern to other viewers.

In the end, I think the film is worthwhile viewing for those who take their religion seriously, without putting any readers here in danger of becoming Christian. Everyone can learn from this giant of faith, who practiced what he preached, and did much to promulgate belief amid a disbelieving world. Though the intellectual challenges of Jew and Christian differ in significant ways, thinking people must confront them, and this lovingly presented film does much to present one model of how it can be done.

David Farkas is a practicing attorney in Cleveland. His notes on the Talmud Bavli were recently published as HaDoresh vehaMevakesh.