The BEST: The Magic Mountain

“The BEST” series features writers considering what things “out there” make us think and feel. What elements in our culture still inspire us to live better? We seek to share what we find that might still be described as “the best that has been thought and said.” Click here to read about “The BEST” and to see the index of all columns in this series.

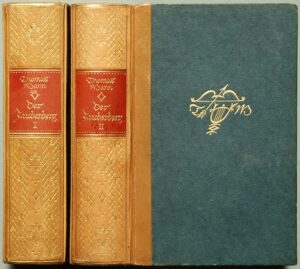

Der Zauberberg (1st German ed., 1924)

Summary

Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain (published in German in 1924) follows Hans Castorp, a young German engineer on his visit to a cousin at the Berghof tuberculosis sanatorium in Switzerland. He sets off for a three-week stay and ends up staying seven years. The suspended world of this quasi-resort town slows time and draws Hans into a life of illness, introspection, and seductive idleness. Mann turns this seemingly static setting into a canvas upon which to capture the spirit of modernity in the years preceding World War I. Mann manipulates time and atmosphere within his writing to portray a Europe that had become facile, stale, and decadent.

Why this is The BEST

From Hans Castorp’s earliest days at the sanatorium, he encounters a world governed by a strange passivity. Its rituals, the rest cure, the endless meals, the languid socializing, create a rhythm in which time evaporates. Gambling fits seamlessly into this environment. Officially prohibited as “harmful,” the games nevertheless flourish in the shadows. This illicit gambling is driven by boredom, inertia, and rebellion born of hopelessness. Gambling becomes a symptom of the deeper malaise at Berghof: a place where people surrender their agency to forces outside of themselves. In such a world, one is no longer an actor but a spectator of one’s own life. Mann presents this as one form of the spiritual disease that afflicts the patients, parallel to their physical illnesses.

Hans’ own attraction to chance expands as he assimilates into sanatorium life. Gambling becomes a metaphor for Hans’ moral drift. Instead of exercising will or responsibility, he yields to circumstances, impulses, and “fate.” This growing surrender is the very opposite of the virtues of discipline and self-determination that he once embodied.

The Magic Mountain portrays a special type of magical thinking, where the principle of cause and effect slowly erodes. This insight can help us better understand the growing popularity of sports gambling within the youth culture of our Jewish communities (recently spotlighted by my colleague R. Larry Rothwachs)—even though Mann wrote long before smartphones. Young people today often turn to these risk-heavy, luck-based ventures not merely out of thrill-seeking but from a deeper belief that ordinary cause-and-effect does not govern their economic lives. As in the Berghof sanitorium, our children are slowly surrendering their agency to forces outside of themselves. If education no longer guarantees a stable livelihood, and if effort is perceived as insufficient to overcome structural barriers, then embracing randomness becomes both a coping mechanism and a worldview. Gambling’s magical thinking—the belief that streaks, hunches, or just blowin’ on the dice influence outcomes—mirrors the broader cultural intuition that success everywhere depends on forces beyond one’s control.

This cultural turn toward luck has an unexpected parallel in parts of the Orthodox Jewish world, particularly within Haredi communities. There too, we find a comfort with chance-oriented frameworks—from ubiquitous charity lotteries to segulot for livelihood, and from miracle narratives of unexpected financial salvation to halakhic discussions legitimizing games of chance. In the responsa of Rabbi Yitzchak Zilberstein (Hashukei Hemed, Kiddushin #601, et al.), for example, lotteries appear as a serious object of analysis, reflecting a worldview that sees a theologically-dicey individual-divine providence, rather than vocational planning or professional development, as the true motor of economic success.

In an environment where secular education is minimized, army service is strongly discouraged, and professional trajectories are sharply limited, the idea that livelihood depends on divine favor (and sometimes literally hitting the lottery) becomes culturally coherent. If conventional cause-and-effect pathways are closed, belief in providential luck becomes an adaptive strategy. This, too, influences the rightward drift in our own communities’ religious orientation. Magical thinking thrives when predictability collapses.

This dynamic is not new to Jewish life. In fact, a revealing historical example emerges from the very season of Hanukka. The most popular Hanukka game is dreidel. While the dreidel’s contemporary framing is innocent, the deeper cultural background connects this winter season to a long history of Jews turning to games of luck.

One of the most vivid testimonies comes from the autobiography of the seventeenth-century Venetian rabbi Leon Modena, Hayyei Yehuda. Modena was a great scholar, preacher, kabbalist, hazzan, polemicist, yet he confesses with remarkable honesty to a lifelong addiction to gambling. Throughout his memoir, he describes the emotional and spiritual pull of games of chance, the way they strained his finances, and the cycles of regret and relapse that defined his adult life. His relapses would happen on Hanukka.

What Modena experienced in seventeenth-century Venice resonates today. Gambling provided him with the illusion of control, a sense that luck—not the slow grind of commerce or scholarship—could solve his problems. He knew better intellectually, yet the psychological appeal of randomness remained irresistible. Modena’s story illuminates our contemporary reality. The modern young-adult who turns to sports betting apps, hoping for the lucky break that will transform his bank account, is not so far removed from Modena Venetian card playing, nor Hans Castorp and the other Berghof patients. All three locate hope in the realm of chance because the realm of predictable cause-and-effect feels insufficient or inaccessible.

It is here that we must turn to Hanukka’s lessons. The Hasmoneans’ story can inspire us to recognize our potential to take ownership over our destinies. May we follow their example of both responsible self-determination and personal courage.

Chaim Strauchler, an associate editor of TRADITION, is rabbi of Cong. Rinat Yisrael in Teaneck.