Transactional Politics: A Critique

Last month, I found myself in Petach Tikva, serving as scholar-in-residence for the Netzach Shlomo community as part of the RCA–Barkai partnership. Over fifty-two hours, I spoke fourteen times (thirteen of them in Hebrew) and engaged in conversations with schoolchildren, teen leaders, and adults. Again and again the questions circled back to antisemitism, and specifically to the troubling fact that thirty percent of Jewish New Yorkers cast their votes for a candidate widely understood to be an anti-Zionist bigot. The concern was palpable: vulnerability, confusion, and a genuine fear about what the future may hold for Jews in New York and beyond.

In Israel, I didn’t have a satisfying answer. But when I returned to Teaneck, I opened Mishpacha Magazine and found a full-throated explanation, not of Jewish voting behavior broadly, but of the logic that drove one Jewish community to embrace Zohran Mamdani.

The profile of Rabbi Moishe Indig, the Satmar askan, offers a remarkable portrait of a political master tactician—a man who has learned how to extract concessions from City Hall, Albany, and Washington with impressive skill. But his success exposes the limits, and even the dangers, of a purely transactional political model. What appears powerful in the short term may hollow out communal responsibility and undermine both American democracy and the Jewish people.

The profile of Rabbi Moishe Indig, the Satmar askan, offers a remarkable portrait of a political master tactician—a man who has learned how to extract concessions from City Hall, Albany, and Washington with impressive skill. But his success exposes the limits, and even the dangers, of a purely transactional political model. What appears powerful in the short term may hollow out communal responsibility and undermine both American democracy and the Jewish people.

While Satmar believes Zionism as an ideology and the State as an entity are the most significant factors harming the Jewish people, mainstream Orthodox Jews do not. Mishpacha Magazine fails to acknowledge that working against Zionism furthers Satmar’s goals. The vision of Jewish politics that the article does present—one devoid of values beyond self-interest—becomes not so much Satmar’s message but that of the article’s author and publisher.

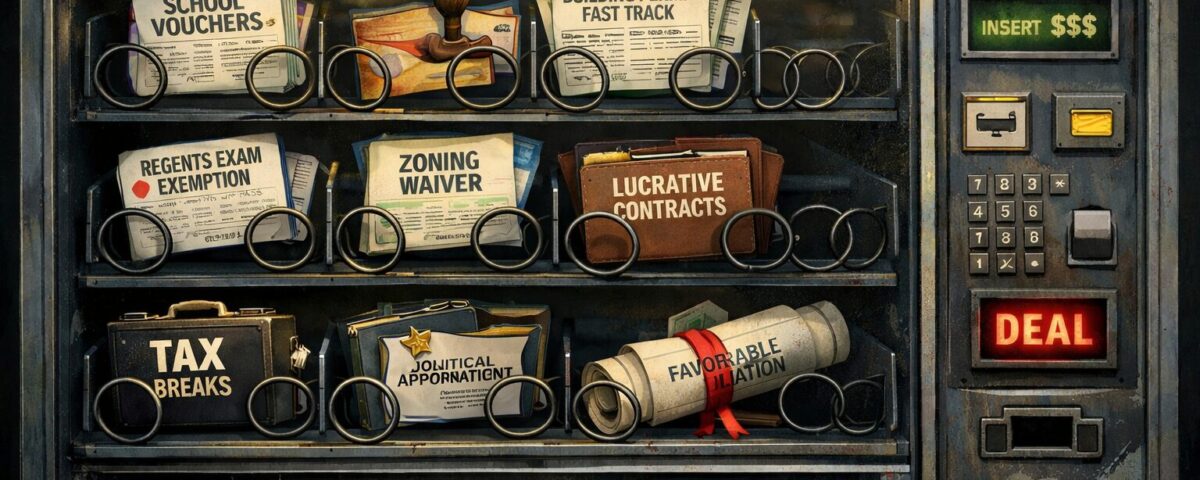

At the core of the article is a vision of civic life as transactional: politics becomes a marketplace in which the goal is to secure the best deal for one’s own enclave. Citizenship is not a shared responsibility toward the Republic but a tool for negotiating carve-outs, exemptions, and protections for one’s immediate group. Mishpacha Magazine treats this as a legitimate strategy for American Jewish politics. It should not.

From the standpoint of American democracy, this is a narrowing of civic purpose. It encourages fragmentation instead of solidarity; quick wins instead of long-term stewardship. Government becomes less a covenant among citizens and more a vending machine dispensing favors to whoever can marshal votes. Yet the most troubling dimension, hinted at but not confronted by the magazine, is what happens when this approach reaches the question of Israel.

Transactional Politics That Stops at the Water’s Edge

In quote after quote, Mishpacha Magazine paints a political philosophy: the political calculus begins and ends with the needs of Williamsburg’s Satmar community. When Israel enters the conversation, this narrowness becomes stark.

Satmar is not Zionist. Yet, the larger American Jewish community is. Mishpacha Magazine platforms Indig as he offers praise for leaders whose policies have been overtly hostile to the Jewish State, and he proudly recounts that his political alliances remain unchanged regardless of their impact on Israel’s security, global Jewish safety, or the stability of the American–Israel relationship.

This is not “Israel as a lower priority.” It is Israel as no priority at all. And that message, spoken publicly and proudly, reverberates far beyond Williamsburg.

Israel is the gravitational center of Jewish identity and the main target of antisemitic fixation. Detaching Jewish political behavior from Israel’s wellbeing reshapes how America understands Jewish civic life. It signals to elected officials that Jews can be split into competing interest groups, played off one another, and negotiated with separately.

Fragmentation Has Consequences.

The world does not distinguish between our sectors. Here lies another danger: the rest of the world does not understand our internal distinctions. Outside of Jewish life, there is no meaningful difference between Satmar, Bobov, Chabad, Modern Orthodox, Conservative, Reform, unaffiliated—or anything in between. To most Americans, “Jewish issues” are either the issues of all Jews or of no Jews.

When one Jewish community publicly supports a politician hostile to Israel, it is not interpreted as Satmar supporting him. It is interpreted as Jews supporting him. When another community lobbies to block funding that affects national policy priorities, the world does not hear “this enclave.” It hears “the Jewish vote.” When Jewish political messages contradict one another loudly enough, they begin to erode the very credibility that has long powered Jewish advocacy in the United States. When internal Jewish divisions become public contradictions, the ability of the Jewish community to advocate for what matters most to us—communal security, democratic freedoms—becomes weaker, not stronger. Fragmentation, when visible to the outside world, reduces influence, breeds doubt, and invites political actors to disengage from Jewish concerns altogether.

A politics built solely on transaction suffers two deep flaws: First, it privileges the immediate over the enduring. If the only question is “What helps my block today?” then broader policy consequences—for education, zoning, public safety, democratic norms—disappear from view. Millions of Americans feel the downstream effects of decisions made with no regard for the common good. Second, it erases the Jewish collective. Jewish history is a story of shared destiny. Whether Satmar agrees with Zionism is irrelevant to this responsibility. Satmar accepts the idea kol yisrael areivim zeh ba-zeh—we are all responsible one for the other. To treat the safety of Israel’s Jews as politically irrelevant is to discard that centuries-old idea of mutual obligation.

Every major Jewish movement of the past century—post-Holocaust advocacy, the fight for Soviet Jewry, bipartisan support for Israel—succeeded because Jews thought beyond themselves. Transactional politics pulls in the opposite direction.

Zionism is often caricatured as tribal self-protection. In truth, it is a call to responsibility, a refusal to be bystanders in history. It insists that Jewish life flourishes only when we take responsibility for all Jews and for the Jewish homeland. Zionism stands in sharp contrast to the political philosophy on display in the Mishpacha profile. Zionism teaches: your choices must strengthen the entire people, wherever they live. The transactional model says: your choices must strengthen your immediate group, and only that.

A Better Model of American Jewish Citizenship

American Jews have never understood themselves as merely another interest group. From Justice Louis Brandeis to Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik, from Jewish war veterans to the activists who fought for both Soviet Jewry and for civil rights, American Jewish civic engagement has been animated by a larger vision: that we are partners in the American project, responsible not only for ourselves but for the health and character of the nation.

Against that rich tradition, the model promoted in the Mishpacha profile feels small. It seeks insulation rather than participation, extraction rather than contribution, isolation rather than solidarity. The Jewish people cannot afford such retreat—not in 2025, not with rising antisemitism, not with Israel under threat, not with American society strained in ways unseen in generations.

Political legitimacy for minority communities increasingly depends on being perceived as contributors to the common good. A community that asks only for itself risks losing the moral authority that once made Jewish advocacy uniquely effective.

Toward a Politics of Responsibility

Communal needs matter. Schools matter. Neighborhoods matter. But they must be pursued within a vision that extends beyond one’s own borders, a vision anchored in our shared destiny. Our politics must ask:

- Does this strengthen the Jewish people as a whole?

- Does this support the State of Israel, the central project of modern Jewish renewal?

- Does this contribute to the long-term health of American democracy and all its citizens?

The political model celebrated in the Mishpacha article answers none of these questions. That absence is the heart of the problem. Jewish political strength has never come only from our ability to negotiate. It has come from our moral seriousness, from the belief that Jews must help build societies rooted in justice, solidarity, and responsibility.

In Petach Tikva, after one of my talks, an elderly man asked me, “How can a Jew living outside Israel be a Zionist?” My answer: by participating in political life on behalf of the Jewish people and on behalf of America.

A politics that abandons Israel, disregards the Jewish collective, and seeks only to extract from the public good is not just shortsighted. It betrays the deepest commitments of our Torah and our history.

The Jewish future demands more. We must do better.

Chaim Strauchler, an associate editor of TRADITION, is rabbi of Cong. Rinat Yisrael in Teaneck.