REVIEW: A Woman is Responsible for Everything

Debra Kaplan and Elisheva Carlebach, A Woman is Responsible for Everything: Jewish Women in Early Modern Europe (Princeton University Press, 2025), 488 pp.

The title of Debra Kaplan and Elisheva Carlebach’s A Woman is Responsible for Everything is a quote from Rivka Tiktiner, a sixteenth-century Jewish author of a book of morals addressed to the women of her day. And indeed, as Kaplan and Carlebach demonstrate, Jewish women in the early modern period were responsible not just for their husbands, children, and homes; they also took on significant roles in the lives of their communities: providing medical care for their neighbors, sewing burial shrouds, overseeing the local ritual bath, fashioning wicks and candles to light the synagogue, feeding the poor, providing for orphans—and, fortunately, often keeping detailed records of their work. Drawing on these communal logbooks and on other literary and material artifacts from the period, Kaplan and Carlebach have written a monumental treatise that uncovers fascinating truths about the structure of Jewish life roughly half a millennium ago.

The title of Debra Kaplan and Elisheva Carlebach’s A Woman is Responsible for Everything is a quote from Rivka Tiktiner, a sixteenth-century Jewish author of a book of morals addressed to the women of her day. And indeed, as Kaplan and Carlebach demonstrate, Jewish women in the early modern period were responsible not just for their husbands, children, and homes; they also took on significant roles in the lives of their communities: providing medical care for their neighbors, sewing burial shrouds, overseeing the local ritual bath, fashioning wicks and candles to light the synagogue, feeding the poor, providing for orphans—and, fortunately, often keeping detailed records of their work. Drawing on these communal logbooks and on other literary and material artifacts from the period, Kaplan and Carlebach have written a monumental treatise that uncovers fascinating truths about the structure of Jewish life roughly half a millennium ago.

The book, subtitled “Jewish Women in Early Modern Europe,” is both deep and far-ranging, covering every known aspect of women’s lives in sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth century Ashkenaz—from Amsterdam in the west to Prague in the east, and from as far north as Copenhagen to as far south as northern Italy—a region united by Yiddish as the lingua franca and shared rabbinic networks. This was the golden age of the Kehilla, a purposeful and highly organized entity with formal membership, administration, and record-keeping. Communal log-books meticulously and copiously documented administrative work performed on behalf of the community—by scribes, charity officials, tax collectors, court judges, mohalim, midwives, mikve attendants, and burial societies. In fact, when it comes to population statistics, the women’s records are far more valuable: Midwives recorded all births, whereas mohalim only noted the boys they circumcised. This culture of record-keeping, combined with a growing literacy among women, reveals aspects of women’s lives in new detail, from recipe books to laundry lists to embroidered samplers to inventories of women’s property taken upon death. As Kaplan and Carlebach note, “What we witness in the early modern period is the written word becoming the primary platform for the business of life itself.”

Another driving force that enveloped women in literary culture was the advent of the printing press in the fifteenth century. While some elite women were able to read Hebrew, the expansion of print to include Yiddish language materials of many genres—Bible translations, prayer books, popular tales, books of morals and customs—motivated more women to learn to read and write, drawing them into greater participation in religious, economic, intellectual, and communal life. Shortly after the introduction of print, early modern Jews assumed that Ashkenazi women would own copies of certain crucial texts; a 1728 Grace after Meals booklet, contains the phrase “ve-al britkha she-hatamta bi-vsareinu (“and the covenant you incised in our flesh”), with the following Yiddish instructions printed above: “This should not be recited by women and girls,” evidence that sufficient numbers of women were indeed capable of reading such texts, and makings use of them, that it warranted a publisher’s investment in printing it. Several books were published with women in mind, such as the seventeenth-century Yiddish translation of R. Moshe Isserles’ Torat Ha-Hattat, a legal work about preparing kosher meat, which, according to its translator, Yaakov Heilpurn, was crucial for ba’alot bayit “because [the women] are at home while the men go to work, leaving the women to cook”; Heilpurn argued that the publication of his translation would “allow some people to learn as well as the rabbis…and then, one wouldn’t have to pay a rebbe” to teach them the laws.

With the proliferation of printed handbooks providing women with greater access to Jewish laws and customs, the tension between print culture and mimetic culture was perhaps first and most deeply felt during this period. In the fifteenth century, Rabbi Jacob Molin had strongly warned against composing a handbook to teach women the laws of menstrual purity; mothers were supposed to pass on these traditions to their daughters. But just one century later, Rabbi Benjamin Slonik insisted that his edition of Seder Mitzvot Nashim could help women who were embarrassed to ask their Nidda questions to a rabbi; he even noted that a woman might incorrectly assume she is menstrually impure, erring on the side of stringency and making “a mistake because she had not read books.” Slonik’s edition proved immensely popular, selling out five printed editions in the span of fifty years and attesting “to the new ways in which halakhic knowledge became accessible through print and to the acceptance of print as a suitable medium for such transfer.,”

As print culture spread, so too did women’s access to education. In some communities, many girls attended elementary school classes, as we know, most famously, from Glikl of Hamelin’s seventeenth-century memoir. Others acquired literacy through informal means, such as embroidering letters, numbers, and words on samplers. Several women pursued scribal arts, such as Sara Oppenheim, who wrote her own Megillat Esther prompting a seventeenth-century rabbinic discussion about whether a scroll written by a woman could be kosher for chanting from on Purim. Hannah of Frankfurt, daughter and wife of a Torah scholar, was remembered for having “sat for twenty-two years in the bet midrash, and used her strength before upright students and scholars, reading and teaching them all of her days.” Rabbi Yair Hayyim Bacharach, author of the Havot Yair, writes that he named his book of rabbinic responsa in memory of his learned grandmother Hava, who studied Midrash Rabbah without translation and “several times when the rabbinic titans of the generation struggled, she came and extended her quill and excelled in writing in the clearest language.” Beyond their own scholarship, women were also involved in every aspect of book production, serving as printers and typesetters.

Although printed texts provide crucial evidence for Kaplan and Carlebach’s scholarship they note that “this book was born in the archives.” Every page contains at least half a dozen references to archival collections in Jerusalem, New York, and various European cities. These hundreds of meticulous citations are staggering, but at times it is frustrating that the endnotes very rarely expand upon the text. After reading about a case in which a woman complained about being violently struck by a man in synagogue even though she was menstrually impure, the curious reader turns to the back of the book to find out more about the issues underlying the presence of menstruating women in synagogue—only to be met with a reference to a logbook from Friedberg documenting that particular case. Also frustrating is the lack of any accompanying map; many readers will be unfamiliar with the location of Friedberg, Altona, Wandsbek, Worms, and the other communities mentioned throughout the book. At times it seems as if the authors—or perhaps the publisher—assumed that the book was intended for a scholarly audience. This fails to account for its more far-reaching appeal and importance outside of the ivory tower.

Readers interested in the history of Jewish customs, for instance, will be fascinated to discover the range of practices that have since faded into oblivion. When a woman returned to synagogue after giving birth, she arrived wearing burial shrouds over her clothing, which she then removed, in a tangible symbol of the brush with death that every childbirth entails. On midday of her wedding day, the bride’s hair was ceremonially braided by married women while the she mourned her virginity and everyone showered her in gifts. According to Christian Hebraist Paul Christian Kirchner, who documented this practice, the Jews think they are “following God’s example, as He braided Eve’s hair, sang before her, and danced with her in paradise”; indeed, according to the Talmud, God braided Eve’s hair before escorting her to Adam (Shabbat 95a). In a chapter on material culture, the authors note based on household inventories that poor women who had only one tablecloth would use one side for dairy and one for meat, marking each side accordingly with the words “halav” and “basar.” Women cooked in shared communal ovens and owned pots inscribed with their names for identification purposes; one such pot from Frankfurt appears in one of many color plate inserts that render A Woman is Responsible for Everything not just a work of academic history, but also a beautiful book worth owning in hard copy.

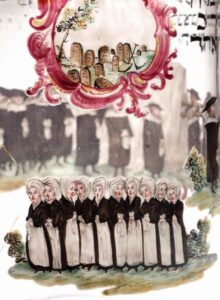

In addition to the many color images, the book is generously illustrated throughout with reproductions of manuscripts and printed books as well as photographs of material artifacts, such that reading this book is like gaining access both to a library archive and to a museum. Several of these images are from central European Seder Birkat HaMazon manuscripts, which illuminate the Grace After Meals and other daily prayers. We see, for instance, a Jewish woman and her maidservant preparing challah for Shabbat, and another woman holding a prayer book and reading bedtime prayers beside her swaddled infant, and yet another woman reciting the Shema while nursing her baby; the inscription above this latter image reads, “Men, women, and children are obligated to recite the bedtime Shema,” which is more inclusive than the language that appears in the Talmud: “Even if he has recited Shema in the synagogue, it is a commandment to recite it at his bed” (Berakhot 4b). In an illustrated book of circumcision laws from eighteenth-century Prague, we see a group of women crowded around the large arched doorway leading into the men’s section to watch a brit. And on a decorative glass tumbler from Prague commissioned by the Hevra-Kadisha, we see tombstones and spades in a graveyard with the members of the burial society featured below; the caption reads, “When facing outward, the tumbler shows only the men in the hevrah; the women remain hidden unless one seeks them out.”

This caption also encapsulates Kaplan and Carlebach’s greatest achievement: Where the early modern women of Ashkenaz would otherwise remain hidden, they have sought them out. In A Woman is Responsible for Everything we discover that the women have been hiding in plain sight all along: They are working in print shops, keeping the family business records, and testifying before notaries in court. They are performing Tashlikh at the riverbank, sitting in the Sukka alongside the men, and holding Haggadot at the Passover table. They are praying in synagogue, teaching Torah, and learning the scribal arts. Given this ample historical precedent, we might argue that women today should be granted more public and professional roles in both Jewish and secular contexts if for no other reason than for the sake of tradition.

Ilana Kurshan, winner of the Sami Rohr Prize for Jewish Literature, is the author of Children of the Book (reviewed in our Summer 2025 issue).