A 17th-Century “Jewish” Medical Diploma

The Medical Diploma of Moses Crespino from the University of Padua (1647): The Only “Jewish” Medical Diploma in History

Jews have had a long and storied relationship with the practice of medicine, of which little physical evidence remains. The medical diploma is one of few tangible representations of this history, allowing us to imagine, if even for a moment, the travails endured by the recipient— the texts of Hippocrates they studied, the dissections they observed, the professors they admired and despised, the challenge of juggling medical study and Torah observance, the antisemitism they likely encountered from both fellow student and faculty alike, the family pride and elation at the completion of training. These struggles all culminated with the transfer of this document into their hands.

There are few extant medical diplomas from Jewish medical graduates before 1700. As Jews were generally banned from European universities, only the rare Jewish physician was university trained. The majority of Jewish physicians trained by apprenticeship, where no diploma would have been issued. The earliest known diploma of a Jewish physician is that of Abraham de Balmes from the University of Naples in 1492, for which special Papal permission was required.1

The first university to officially accept Jewish medical students, beginning in the sixteenth century, was the University of Padua.2 Though we find the rare medical diploma from other universities, the majority of extant diplomas of Jewish medical graduates are primarily from Padua, and even these are scarce.3 Here I discuss one such diploma which has previously escaped notice by historians, and which to date is the earliest known example of a diploma of a Jewish medical graduate from Padua.4 The diploma was granted to Moses Crespino in 1647.

Its importance however lies not in its primacy.

Moses Crespino is not mentioned in any works on Jewish physicians, nor to my knowledge in any other historical works. From the diploma we learn that his father’s name was Abraham. There was a Crespino family in Northern Italy in the 1600s, and the name Moses is found in the family, but I have been unable to identify any record of our graduate.5 The only record I have found of Moses Crespino’s existence, outside of the document under discussion, is one line from the University of Padua Archives, cited in Modena and Morpurgo’s work on the Jewish graduates of the University of Padua.6 It reads, “Crespino Moisè, ebreo florentino, immatricolato 1 febbraio 1647” (The Florentine Jew Moses Crespino matriculated February 1, 1647). Matriculation is akin to our university registration and a student could matriculate multiple times over the years. There could have been other matriculation records that preceded this one which are no longer extant. Upon graduation, the archival record would typically contain an expansive record, including the professors who promoted the student and other aspects of graduation.7 There is no graduation record in the archives for Crespino, and Modena and Morpurgo provide no additional information, as they do for the other students mentioned in their work.8

The Diploma

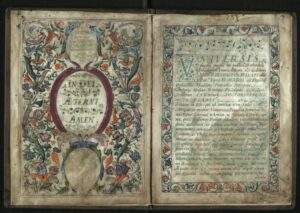

Crespino’s diploma shows his graduation date to be May 22, 1647. While the matriculation record identifies him as a Florentine Jew, the diploma identifies him as “Moyses Crespinim Pisanum,” from Pisa, a city under Florentine rule at this time.

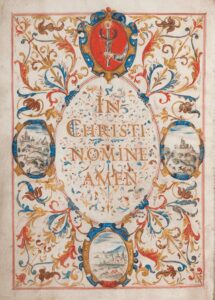

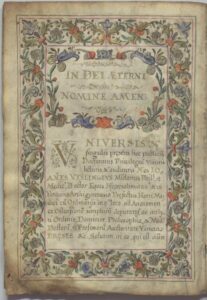

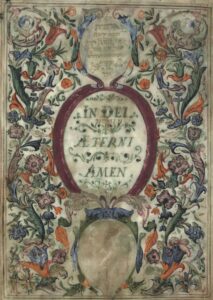

In comparing the diploma of Crespin to the typical diploma of a Catholic graduate, one finds two differences. The invocation of a typical diploma would read “In Christi Nomine Amen” (in the Name of Christ Amen). The diploma of William Harvey (Padua, 1602) is below:

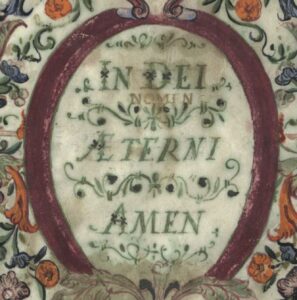

Crespino’s invocation reads instead, “In Dei Aeterni Amen” (in [the name of] the Eternal God, Amen).

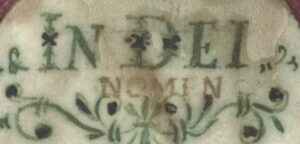

A close inspection of the invocation reveals that the word “NOMEN” is added under the word “Dei.”

With the addition, it would read “In Dei Nomen Aeterni Amen” (In the Name of the Eternal God, Amen). It is not of the same calligraphy or pen as the other words of the invocation and appears to have been added at a later time.

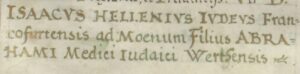

Just two years later, we find a similar altered invocation for the graduate Isaac Hellen (1649).9

It is this later exact formulation of the invocation, “In Dei Aeterni Nomine, Amen” (In the Name of the Eternal God, Amen) which became standard for the diplomas of subsequent Jewish medical graduates.

In addition, the description of the location of Crespino’s graduation ceremony is listed just as “in loco solito examinu” (in the usual place of examination), as opposed to the usual “in Episcopali Palatio in loco solito” (in the Episcopal Palace, the usual place…).

Both of these changes are found in multiple diplomas of Jewish graduates of Padua, though they appear here earlier than other cases. They represent examples of accommodations, of which there were others for the Jewish graduate.10 Instead of invoking the name of Christ on one’s diploma, the Jews were allowed to invoke the name of the Eternal God (Dei Aeterni). In addition, while the graduation ceremony for the typical student was held in a church, the Episcopal Palace, the ceremonies of the Jewish students were held in a non-ecclesiastic venue. The words “Episcopal Palace” were simply deleted from the text of the diploma. This omission/deletion is found in virtually all Jewish diplomas. One common addition to the diploma of the Jewish student is omitted in Crespino’s case. The name of the Jewish graduate is often followed by the word “Iudeus” or “Hebreus,” identifying their Jewish origin. This term is absent in Crespino’s diploma, though it was included in his brief matriculation record cited above. Hellen’s diploma includes this identifier:

On first pass, this is a beautiful decorative graduation record, and a fine and early example of a diploma of a Jewish medical graduate from Padua.11 Aside perhaps from its precedence, being the earliest extant diploma of a Jewish medical graduate from Padua, it does not appear to be historically unique. The diploma of Isaac Hellen, which includes the term “Iudeus,” was issued only two years later. Other Jewish diplomas are more ornate and include portraits and family crests. Virtually all the diplomas of Jewish graduates include the alteration to the invocation found in Crespino’s diploma, and most include the Jewish identifier, such as Hebreus, which Crespino’s does not.

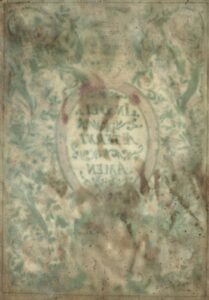

There is however one feature of this diploma that makes it truly exceptional. On the front page, in a word “balloon” above the invocation, appears a faint inscription.

The inscription is in block Hebrew characters and is comprised of a verse from Psalms 111:10:

ראשית חכמה יראת ה’ שכל טוב לכל עשיהם תהלתו עמדת לעד

“The beginning of wisdom is the fear of the Lord; all who practice it gain sound understanding. Praise of Him is everlasting.”

This verse is recited daily by Jews upon awakening as part of daily morning prayers. This inscription begs the questions: Was it found in other Jewish diplomas? Who inscribed it and when was it added? Was this inscription written by the same hand as the word “NOMEN” in the invocation? More fundamentally, what is a Hebrew excerpt from Psalms doing on a medical diploma? This is a unique exemplar unknown to Jewish (medical) historians.12

Jewish Medical Diplomas vs. Non-Christian Medical Diplomas

The University of Padua hired and licensed a staff of diploma writers and illuminators, and there was a standard template for the medical diploma text.13 As mentioned previously, the diploma of the Jewish medical graduate of Padua contained emendations, omissions or additions to the standard-issue diploma. In addition to the changes discussed, religious images or iconography, which were commonplace in the other diplomas, were conspicuously absent, and often the year of the diploma, which typically included a Christian reference (such as anno a Christi Nativitate or anno Domini) was altered as well (e.g., anno currente). The students made great efforts to omit any Christian references or allusions in the document.

I have used the term “Jewish” to describe the diplomas designed for the Jewish students.14 However, upon viewing Crespino’s diploma I realize that I was in error. A more accurate term would be a “non-Christian diploma.” While the students clearly went to great efforts to partially or sometimes entirely remove the Christian references, they did not take initiative to add any specifically Jewish references.15

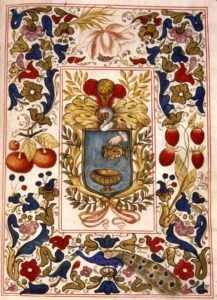

Some of the diplomas do include the family coat of arms, and in some cases, these have Jewish themes. The crest of Samuel Coen (Padua, 1702) includes the traditional hand configuration of a Kohen during the recitation of the priestly blessing.16

The family crest in the diploma of Jacob Levi (Padua, 1684)17 depicts the pouring of water from a gold pitcher into a gold receptacle as the Levites poured water over the hands of the Kohanim.

These symbols were frequently found in the crests of families with these last names. This however does not constitute a Jewish addition to the diploma by the student, per se, as they were simply adding their family crest as other students did. The traditional family crest was not altered or created for the diploma. It just so happened that there was Jewish imagery in some of the family crests, while in others there was not. Furthermore, it would not be necessarily discernible to an observer that the images were specifically Jewish.

Some of the diplomas include portraits of great physicians of the past. One scholar has suggested that the diploma of one Jewish student, Emanuel Colli (Padua, 1682) includes the picture of a rabbi standing next to a physician.18 Admittedly, the figure does look somewhat rabbinic, but I believe the identification as a rabbi to be mistaken. This diploma was illustrated by Johannes Aloysius Foppa, an official illuminator of the University of Padua.19 Foppa also illustrated the diploma of Gershon Tilche (Padua, 1687). There we find the very same figure, though he is identified as Hippocrates, and while certainly a sage, was not of rabbinic origin.

Figures that could have been included in a Jewish student’s diploma include Moses or possibly Maimonides.20 Perhaps a student could have requested of Foppa to write “Maimo” or “Moses” over one of the figures. One could argue that these figures were not part of the student’s medical training per se, thus precluding their inclusion. However, the Christian student diplomas included depictions of Mary Magdalene or Mother and Baby, who were clearly not part of their medical education.

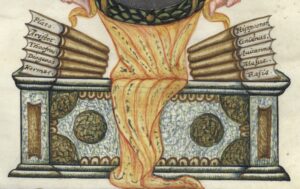

In Coen’s diploma we find an image of a library.

The authors’ names are engraved into the top of each book. I searched in vain for a Jewish author. These are the classic works of the medical curriculum of this period- Plato, Aristotle, Hippocrates, Galen, Avicenna, and others. Could he possibly have slipped in Maimonides as one of the books?]

While I suggest places in the diploma that could have accommodated Jewish-related insertions, this of course may simply have never entered the mind of a Jewish student, nor have even been possible. Given the general climate against Jews, and in particular Jewish physicians, the concessions they received were already far more than could be expected. The university may also have had limitations as to the changes to the diploma template that could be made. Thus, while the diplomas of the Jewish Padua graduates were “non-Christian,” they were not specifically “Jewish.”

Crespino’s Addition

Given this background, the insertion into Crespino’s diploma of Hebrew writing is all the more exceptional. How did the Hebrew inscription come to appear in this document? Was it part of the original university-issued diploma, or was it added at a later date?

The text does not appear to be the same ink color as the remainder of the diploma.21 Possible proof is gleaned from viewing the obverse side of the page:

While the letters of the center invocation, as well as the artwork, are clearly visible in reverse, the Hebrew words in the upper balloon are not clearly discernible, reflecting that there were likely written with a different instrument and at a different time.

The calligraphy in block Hebrew script is from a skilled competent scribe of Hebrew characters. The university-hired illustrators and scribes would unlikely have been versed in Hebrew. However, the text is not perfectly symmetrical, nor the lines straight. The very first word appears to be misspelled with the aleph and resh transposed.22 If this text were part of the original diploma, the artist would likely have added text or illustration to the bottom balloon as well to maintain symmetry.

Furthermore, if the university offered Hebrew text as an option for a graduating Jewish student’s diploma, surely subsequent graduates would have availed themselves of this option. I am therefore inclined to believe that the text was added later by the student. Even if it were added by the university artists, it would have been upon the student’s specific request. In either case, this is the only example I have found of specifically Jewish content in a Padua or any medical diploma.23

What would possess a young Jewish student to “Judaize” his diploma in this fashion? I believe this reflects a longstanding tradition of Jewish physicians relating their medical training, practice, and knowledge to their Jewish tradition. This has manifested itself in a number of ways, from the very choice of medicine as a profession,24 to the attempt to maintain Jewish education throughout the time-consuming training and practice of medicine,25 to choosing Jewish-themed topics for their required medical school dissertations,26 to writing Hebrew language, Jewish-themed poetry in honor of their graduation from medical school,27 to writing about the halakhic aspects of medical practice.28 Throughout history the Jews have always practiced medicine through the lens of Torah.

Whether added by the university illustrators at Crespino’s behest, or later by the student himself, Crespino nonetheless converted this memento of his medical education into a “Jewish” diploma. It therefore appears that while there are numerous extant examples of “non-Christian” diplomas of Jewish medical graduates of Padua, there is only one example of a “Jewish” diploma, that of Moses Crespino. Indeed, it may possibly be the only “Jewish” medical diploma in history.

Rabbi Edward Reichman, M.D., is a Professor of Emergency Medicine at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine and holds the Rabbi Isaac and Bella Tendler Chair in Jewish Medical Ethics at Yeshiva University. He is the author, most recently, of The Anatomy of Jewish Law: A Fresh Dissection of the Relationship Between Medicine, Medical History and Rabbinic Literature, and Pondering Pre-Modern(a) Pandemics in Jewish History: Essays Inspired by and Written during the Covid-19 Pandemic by an Emergency Medicine Physician.

Image Credits: Diploma of Moses Crespino, courtesy of the National Library of Israel (Jerusalem); Diploma of Isaac Hellen, courtesy of the Germanisches Nationalmuseum (Nuremberg); Diploma of Jacob Levi, courtesy of the U. Nahon Mueum of Jewish Italian Art (Jerusalem); Diploma of Samuel Coen, courtesy of the Archives of the University of Padua, Center for the History of the University of Padua; Diploma of William Harvey, courtesy of the Royal College of Surgeons (London).

- Giancarlo Lacerenza and Vera Schwarz-Ricci, “Il Diploma di Dottorato in Medicina di Avraham ben Me’ir de Balmes (Naploli 1492),” Sefer Yuhasin 2 (2014), 163-193.

- On the Jews and the University of Padua see, A. Ciscato, Gli Ebrei in Padova (1300-1800) (Arnaldo Forni Editore, 1901); S. Dubnov, “Jewish Students at the University of Padua,” American Hebrew Yearbook (1931), 216-219; Jacob Shatzky, “On Jewish Medical Students of Padua,” Journal of the History of Medicine 5 (1950), 444-47; Cecil Roth, “The Qualification of Jewish Physicians in the Middle Ages,” Speculum 28 (1953), 834-843; David B. Ruderman “The Impact of Science on Jewish Culture and Society in Venice (with Special Reference to Jewish Graduates of Padua’s Medical School)” in his Jewish Thought and Scientific Discovery in Early Modern Europe (New Haven, 1995); S. G. Massry, et. al., “Jewish Medicine and the University of Padua: Contribution of the Padua Graduate Toviah Cohen to Nephrology,” American Journal of Nephrology 19:2 (1999), 213-221; S. M. Shasha and S. G. Massry, “The Medical School of Padua and its Jewish Graduates” (Hebrew), Harefuah 141:4 (April, 2002), 388-394; Kenneth Collins, “Jewish Medical Students and Graduates at the Universities of Padua and Leiden: 1617-1740,” Rambam Maimonides Medical Journal 4:1 (January, 2013), 1-8.

- See E. Reichman, “Confessions of a Would-be Forger: The Medical Diploma of Tobias Cohn (Tuviya Ha-Rofeh) and Other Jewish Medical Graduates of the University of Padua,” in Kenneth Collins and Samuel Kottek, eds., Ma’ase Tuviya (Venice, 1708): Tuviya Cohen on Medicine and Science (Muriel and Philip Berman Medical Library of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 2019), 79-127. I have thus far identified nineteen extant diplomas of Jewish medical graduates prior to 1816 from the University of Padua.

- The diploma is part of the collection of Isaac Israel Wallich in the National Library of Israel (system no. 990034232880205171). It is freely available online: (https://www.nli.org.il/he/manuscripts/NNL_ALEPH003423288/NLI#$FL13433565).

- Personal conversation with Leon B. Taranto (June 12, 2022), who has researched and written about the Crespino family, including a branch in Northern Italy in the 1600s, but he has no knowledge of our Moise Crespino, nor of any members of the Crespino family that either lived in Pisa or became physicians. See his three-part series, Leon B. Taranto, “The Taranto-Capouya-Crespin Family History: A Microcosm of Sephardic History,” published in Sephardic Horizons 1:4 (Summer-Fall 2011), 2:1 (Winter 2012), 2:2 (Spring 2012).

- Abdelkader Modena and Edgardo Morpurgo, Medici E Chirurghi Ebrei Dottorati E Licenziati Nell Universita Di Padova dal 1617 al 1816 (Bologna, 1967), 128.

- The formal diploma, which would be granted to the student, would contain this text as well as some additions, including the names of witnesses who were in attendance at the ceremony.

- According to the University of Padua Archives a number of graduation records from this period have been lost. My profound thanks to Francesco Piovan, Chief Archivist of the University of Padua, for this information and for his continued assistance and kindness. The Archives has only very few gaps from the sixteenth century onwards.

- Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Studiensaal Archive, HA, Pergamenturkunden, Or. Perg. 1649 Juli 09. On this diploma, see Moritz Stern, “Das Doktordiplom des Frankfurter Judenarztes Isaak Hellen (1650),” Zeitschrift fur die Geschichte der Juden in Deutschland 3 (1889), 252-255. In Stern’s article on the diploma, the library location is listed under an old cataloguing number, Nr. 5097.

- I have discussed these accommodations extensively elsewhere. See E. Reichman, “Tuviya,” op. cit.; E. Reichman, “The ‘Doctored’ Medical Diploma of Samuel, the Son of Menaseh ben Israel: Forgery of ‘For Jewry’,” Seforim Blog (March 23, 2021).

- It does not include a portrait or coat of arms, which can be found in a number of diplomas of Jewish graduates. See E. Reichman, “Tuviya,” op. cit.

- The NLI catalog makes no mention of this inscription.

- See G. Baldissin Molli, L. Sitran Rea, and E. Veronese Ceseracciu, Diplomi di Laurea all’Università di Padova (1504–1806) (Università degli studi di Padova, 1998).

- See Reichman, “Confessions,” op. cit.; idem, “The ‘Doctored’ Medical Diploma of Samuel, the Son of Menaseh ben Israel: Forgery of ‘For Jewry’,” Seforim Blog (March 23, 2021); idem, “Samuel Vita Della Volta (1772-1853): An Underappreciated Bibliophile and his Medical ‘Diploma’tic Journey,” Seforim Blog (November 5, 2021).

- I do not consider the addition of the identifier “Hebreus” to be a Jewish addition as this was added by the institution.

- The Coen diploma is housed in the Archives of the University of Padua, Raccolta Diplomi, 33 (n. 3841). I thank Francesco Piovan of the Padua Archives for furnishing me with a copy. The family name Coen or Cohen does not always reflect one’s status as a member of the Kohen tribe, but it clearly does in this case. Another famous Kohen graduate of Padua was Tobias Cohen (Tuviya Katz), the author of Ma’aseh Tuviya.

- Umberto Nahon Museum of Italian Jewish Art in Jerusalem, ON0076.

- See Francesco Spagnolo, “Medical Diploma of Emmanuel Colli 1682,” in Venice, the Jews and Europe 1516–2016, ed. D. Calabi, Ch. Huw Evans, D. Kerr, S. Notini, and L. Rosenberg (Marsilio, 2016), 203.

- On Foppa, see G. Baldissin Molli, L. Sitran Rea, and E. Veronese Ceseracciu, Diplomi di Laurea all’Università di Padova (1504–1806) (Università degli studi di Padova, 1998), 41ff.

- While Jewish medical students may not have had access to Rambam’s medical writings, they nonetheless were familiar with and referred to his philosophical and halakhic works. Maimonides is mentioned in a number of Jewish medical student dissertations of this period. See, for example, Salomon Bernard Wolffsheimer, De causis foecunditatis Ebraeorum nonnulis sacri codicis praeceptis innitentibus (Frediriciana, 1742), 27; Salomon Levie, De Semine (Utrecht by the Rhine, 1769), 2. David De Haro, one of the first Jewish medical graduates of the University of Leiden (1633) had a copy of Rambam’s Mishneh Torah in his library. See Catalogvs librorvm medicorum, philosophicorum, et Hebraicorum, sapientissimi, atque eruditissimi viri (Amsterdam: Jan Fredricksz Stam, 1637). A copy of the catalogue is held in the Merton College Library in Oxford, Shelfmark 66.G.7(12) (Provenance: “Griffin Higgs”). I thank Verity Parkinson of the Merton College Library for her assistance in procuring a copy of the catalogue. For more on De Haro, see E. Reichman, “A ‘Haro’ing Tale of a Jewish Medical Student: Notes on David de Haro (1611-1636): The First Jewish Medical Graduate of the University of Leiden,” Bibliotheca Rosenthaliana, in press.

- It also does not appear to be the same ink as the word “Nomen” which was clearly added at a later time.

- In addition, the proper name of God appears to be spelled in full, though I am unable to discern if the leg of the letter “hey” was intentionally altered.

- There is one example of a medical diploma with Hebrew script, but it is a complete Hebrew translation of the medical diploma of Abraham Van Oven from Leiden in 1759. See NLI 990001277300205171. The Latin and Hebrew diplomas appear on the first pages. Aside from the script, there is nothing uniquely Jewish about the content of the document. Our discussion excludes diplomas issued in Israel in the Modern era which may possibly include Jewish-related content.

- E. Reichman, “The Jewish Attraction to the Medical Profession in Physicians’ Own Words: A Mesorah of Medicine,” forthcoming.

- E. Reichman, “The Yeshiva Medical School: The Evolution of Educational Programs Combining Jewish Studies and Medical Training,” TRADITION 51:3 (2019), 41-56.

- E. Reichman, “The History of the Jewish Medical Student Dissertation: An Evolving Jewish Tradition,” in J. Karp and M. Schaikewitz, eds., Sacred Training: A Halakhic Guidebook for Medical Students and Residents (Ammud Press, 2018), xvii- xxxvii.

- E. Reichman, “How Jews of Yesteryear Celebrated Graduation from Medical School: Congratulatory Poems for Jewish Medical Graduates in the 17th and 18th Centuries: An Unrecognized Genre,” Seforim Blog (May 29, 2022).

- In the modern era, many Jewish physicians have written on medical halakha, including Dr. Fred Rosner, Dr. Abraham Abraham, Rabbi Dr. Mordechai Halperin and Rabbi Dr. Avraham Steinberg. For an earlier example, see E. Reichman, “The Life and Work of Dr. Menachem Mendel Yehuda Leib Sergei: A Torah U’Madda Titan of the Early Twentieth Century,” Hakirah 27 (Fall 2019), 119-146.