Alt+SHIFT: Agadat Hurban

Alt+SHIFT is the keyboard shortcut allowing us quick transition between input languages on our keyboards—for many readers of TRADITION that’s the move from Hebrew to English (and back again). Yitzchak Blau continues this Tradition Online series offering his insider’s look into trends, ideas, and writings in the Israeli Religious Zionist world helping readers from the Anglo sphere to Alt+SHIFT and gain insight into worthwhile material available only in Hebrew. See the archive of all columns in this series.

In the past three decades, the Religious Zionist community in Israel began to make its mark in film and television. The Ma’aleh School of Film, Television and the Arts, the first religious film school, opened in 1989 and its graduates have produced such successful television shows as Srugim, Shtisel, and Shababnikim. These shows feature religious characters freed from traditional stereotypes who are revealed in their complete and complex humanity. A Ma’aleh student won a BAFTA award for a film about the Holocaust titled Girl No. 60427. I would also recommend a short and powerful film called Cohen’s Wife.

Several religious individuals unconnected to Ma’aleh have also made a cinematic impact. Rama Burshtein’s Fill the Void, Joseph Cedar’s Footnote, and Shuli Rand’s Ushpizin all deservedly received critical acclaim. Apparently, the fullness of life called for in a Jewish state inspires greater efforts and achievements in the totality of human experience which includes film and television. American and British Orthodoxy have not yet shown parallel creativity.

Several religious individuals unconnected to Ma’aleh have also made a cinematic impact. Rama Burshtein’s Fill the Void, Joseph Cedar’s Footnote, and Shuli Rand’s Ushpizin all deservedly received critical acclaim. Apparently, the fullness of life called for in a Jewish state inspires greater efforts and achievements in the totality of human experience which includes film and television. American and British Orthodoxy have not yet shown parallel creativity.

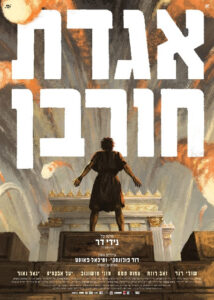

The latest significant addition to the religious Israeli film scene was the summer 2021 Agadat Hurban co-written by Gidi Dar and Shuli Rand. This animated film, based on the story of the destruction of the second Temple, as recounted by Josephus and the Talmudic agadot (Gittin 55b-58a), poignantly depicts the dangers of communal infighting that led to the tragedy. The lesson for contemporary Israeli society clearly emerges. In fact, some film critics found the movie overly didactic.

In the film, Ben Batich (Abba Sikra in the Talmudic tale), the nephew of R. Yohanan ben Zakkai, confronts the choice of pacifism/appeasement versus a possibly futile war against the Roman Empire. His uncle and the Sages represent the non-military position. Having chosen the latter option, Ben Batich then faces the dilemma of rival zealot groups. He first works with and then departs from the faction led by Shimon bar Giyora. When Yohanan from Gush Halav arrives from the North, the zealots must decide if the varying groups can work together. The corrupt priests are another faction with their emphasis on the sacrificial order. In addition, tension exists between the wealthy aristocrats and the poor Jews suffering under Roman taxation. Another important character is Queen Berniki who tries to win over Titus and save the Jewish monarchy and the Temple.

Agadat Hurban does a fine job of appreciating the different perspectives while blaming all of them for contributing to the destruction. As the Talmud reports, the warring factions end up destroying the food supplies of the Jerusalem Jews under siege thereby forcing them to fight. During the Roman-Jewish War (66-70), the Jews did a remarkable job temporarily holding off the mighty Roman Empire. However, internal battles made ultimate victory absolutely impossible.

[Watch Agadat Hurban here — not available in all locations.]

Beyond its important theme, the movie is technically interesting. Rather than employ regular animation, artists Michael Faust and David Polonsky drew more than 1,500 still portraits. Despite the lack of movement a moviegoer would experience from human actors or standard animation, the film, to my mind, manages to convey drama and emotion.

Before the last Israeli election, Betzalel Smotrich spoke in my community and said that Israel currently faces grave challenges from its hostile neighbors but he is not concerned about our internal strife. According to Smotrich, we may argue, but, at the end of the day, the army and other institutions remain unifying factors. During the question period, I argued that it was the exact opposite and that our inner discord represents a more pressing danger. A half-year later, with raging debate about judicial reform, extreme rhetoric from both right and left, and the threat by some of refusal to serve army reserve duty, I think it clear that I was right. It is an excellent time to see this movie.

Yitzchak Blau, Rosh Yeshivat Orayta in Jerusalem’s Old City, is an Associate Editor of TRADITION.