Alt+SHIFT: Minhat Hinukh Scholarship

Alt+SHIFT is the keyboard shortcut allowing us quick transition between input languages on our keyboards—for many readers of TRADITION that’s the move from Hebrew to English (and back again). Yitzchak Blau continues this Tradition Online series offering his insider’s look into trends, ideas, and writings in the Israeli Religious Zionist world helping readers from the Anglo sphere to Alt+SHIFT and gain insight into worthwhile material available only in Hebrew.

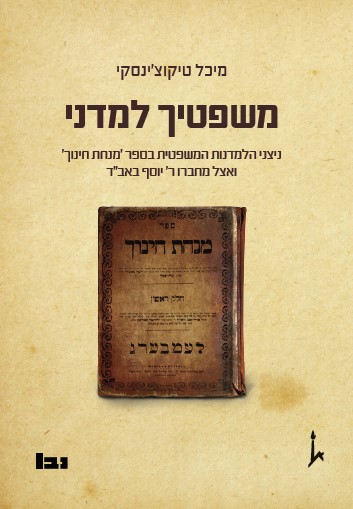

Michal Tikochinsky, Mishpatekha Lamdeni: Nitzanei ha-Lamdanut ha-Mishpatit bi-Sefer “Minhat Hinukh” ve-Etzel Mehabro R. Yosef Babad (Hebrew University, 2020), 498 pages

Yeshiva students cherish the intellectual excitement and almost playful creativity of R. Yosef Babad’s Minhat Hinukh but due to its length and complexity, few academic scholars have written about this important work. Dr. Michal Tikochinksy, head of the women’s beit midrash at Heikhal Shlomo (Mikhlelet Herzog) and of the women’s halakha program at Migdal Oz, deserves great credit for her volume on Minhat Hinukh, a revised form of her doctorate. I would have awarded her a doctorate simply for the impressive feat of reading every word in this massive tome even absent her helpful analysis.

R. Babad (1801-1874) was the Rav of several Galician cities including Ternopil. Due to the unfortunate death of several wives he was married four times; one of his wives was the sister of R. Haim Halbertsam of Sanz. He was not very involved in communal controversies or psak and dedicated his time mostly to study and writing. To give a sense of how different life was in the nineteenth century, R. Babad frequently lacked access to a Talmud Yerushalmi or to a Mekhilta and other midrashei halakha. This hardship seems quite foreign to contemporary rabbis who assume they can locate any rabbinic source on the internet.

R. Babad (1801-1874) was the Rav of several Galician cities including Ternopil. Due to the unfortunate death of several wives he was married four times; one of his wives was the sister of R. Haim Halbertsam of Sanz. He was not very involved in communal controversies or psak and dedicated his time mostly to study and writing. To give a sense of how different life was in the nineteenth century, R. Babad frequently lacked access to a Talmud Yerushalmi or to a Mekhilta and other midrashei halakha. This hardship seems quite foreign to contemporary rabbis who assume they can locate any rabbinic source on the internet.

Tikochinsky identifies central themes in R. Babad’s thought. Perhaps most famously, he was interested in “split halakhic personalities” such as the half-slave half-freeman and the androgynous who may be a man, a woman, a combination, or a gender unto itself. The Talmud already discusses such individuals but R. Babad significantly extended the range of the questions involving them. He even created cases of a half-kohen and a half-convert.

This playful aspect manifests itself in creating paradox cases with endless loops. What happens if witnesses testify that they saw the new moon and it is therefore now Rosh Hodesh Adar and then two boys who turn thirteen on that Rosh Hodesh Adar do hazama and nullify the first pair of witnesses? If we believe the second pair, then the new month has not yet arrived and they were not yet of age to give testimony and we should reinstitute the first pair which will, in turn, engender the same loop. Analogously, what happens when a mohel violates Shabbat by performing a circumcision on the Sabbath when it is after the eighth day and a forbidden act? We should declare him a mumar (a type of sinner) and invalidate the brit. If we do so, it turns out that he did not violate Shabbat as his act was not constructive. Again, R. Babad creates an ongoing circle difficult to escape from.

R. Babad extensively categorized different kinds of mitzvot. There are straightforward obligations (eating matza on the night of the fifteenth of Nissan), situational obligations (building a protective fence only if one has a roof, wearing tzitzit only when one has a four-cornered garment), miztvot kiyumiyot or non-obligatory acts that are mitzvot (saying the priestly blessing a second time on a given day), and mitzvot that are truly just procedural (if a couple gets divorced, here is the halakhic way to do so). He also discusses whether certain mitzvot are one-time acts or a continuous state. It is a commandment to engage in marital relations or to have children? Is circumcision about the act or about the state of being circumcised?

Less famously, R. Babad derives halakhic rulings directly from pesukim even in scenarios where Hazal had not done so. When two people jointly make a graven image, they are both liable since the biblical verse that prohibits this behavior appears in the plural form. Even though Jewish authorities cannot appoint a queen, perhaps a woman can inherit the monarchy since the relevant verse speaks of appointing a king (“som tasim”). Tikochinsky notes the somewhat radical nature of these creative halakhic derivations.

Having highlighted some salient methodologies, she moves on to address the relationship between Minhat Hinukh and earlier rabbinic literature. Though ostensibly framed as a commentary on the Sefer ha-Hinukh, the “commentary” extends well beyond the discussion of the earlier book and is usually studied independently. For example, in the context of the mitzva to honor one’s parents, R. Babad discusses the nature of the obligation to honor an older brother, a topic not addressed by the Sefer ha-Hinukh itself. At the same time, R. Babad does comment on the Hinukh even making careful inferences from its language. Unlike his medieval predecessor, R. Babad was uninterested in offering reasons for mitzvot, an endeavor central to the Sefer ha-Hinukh.

Rambam plays a dominant role in the Minhat Hikunh. Tikochinsky points out that R. Babad refers to the author of Sefer ha-Hinukh as “ha-mehaber” but calls Rambam “rabbenu.” He dedicates time to reconciling Maimonidean contradictions, supplying sources for Rambam’s rulings, and noting Rambam’s methodological tendencies such as utilizing novel derashot for halakhot established in the Gemara based on other scriptural grounds.

According to Tikochinsky, Peri Megadim and Sha’agat Arye were works that influenced R. Babad. He cites both of them numerous times and they bear a certain resemblance of focus. In his introduction to Or ha-Hayyim, Peri Meggadim also outlines various halakhic personalities and categorizes different kinds of mitzvot. Regarding both issues Minhat Hinukh expands and extends the categories.

Minhat Hinukh’s analysis often shares a good deal with the Brisker conceptual approach. Asking if a mitzva is the action or the result is a classic Brisker hakira. Does tashbitu demand an act of destroying hametz or does it simply mean not having leavened bread in the house? If a boy becomes an adult (through physical puberty) on Shabbat morning, is he now biblically obligated to recite kiddush? Is the ability to say biblical kiddush Shabbat morning an extended time period of the original obligation or a tashlumim makeup period?

Tikochinsky locates growing interest in the Sefer ha-Hinukh in the first half of the nineteenth century which increases significantly after the publication of Minhat Hinukh. In addition to all his other contributions, R. Babad may have revived interest in an important work from six hundred years before his time.

Yitzchak Blau, Rosh Yeshivat Orayta in Jerusalem’s Old City, is an Associate Editor of TRADITION.