Alt+SHIFT: Yoel Bin-Nun’s Holiday Duality

Alt+SHIFT is the keyboard shortcut allowing us quick transition between input languages on our keyboards—for many readers of TRADITION that’s the move from Hebrew to English (and back again). Yitzchak Blau continues this Tradition Online series offering his insider’s look into trends, ideas, and writings in the Israeli Religious Zionist world helping readers from the Anglo sphere to Alt+SHIFT and gain insight into worthwhile material available only in Hebrew.

Yoel Bin-Nun, Zakhor veShamor: Teva veHistoria Nifgashim beShabbat uveLuah haHagim (Tevunot, 2015), 513 pages.

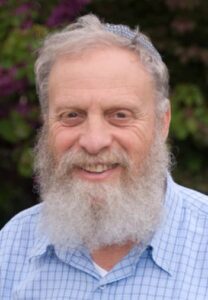

Several individuals deserve credit for the resurgence of Tanakh study in our era. Prof. Nechama Leibowitz’s close readings of the classical commentators shows the advantages and disadvantages of varying approaches. R. Mordechai Breuer’s “two aspects” provides a tool for interpreting scripture and serves as a potential response to biblical criticism. Literary techniques of Robert Alter and Meir Sternberg such as leitwort, type scenes, gap-filling, and the like, made their way into the beit midrash with Yonatan Grossman being the best contemporary practitioner. R. Yoel Bin-Nun, one of the paratroopers who liberated the Temple Mount and a founder of Gush Emunin who subsequently moved more politically leftward, incorporates the realia of geography, topography, history, and archeology. His Zakhor veShamor plays to his strengths and interests, as it explores the Jewish calendar and holiday cycle through the prism of the agricultural reality in the Land of Israel.

Several individuals deserve credit for the resurgence of Tanakh study in our era. Prof. Nechama Leibowitz’s close readings of the classical commentators shows the advantages and disadvantages of varying approaches. R. Mordechai Breuer’s “two aspects” provides a tool for interpreting scripture and serves as a potential response to biblical criticism. Literary techniques of Robert Alter and Meir Sternberg such as leitwort, type scenes, gap-filling, and the like, made their way into the beit midrash with Yonatan Grossman being the best contemporary practitioner. R. Yoel Bin-Nun, one of the paratroopers who liberated the Temple Mount and a founder of Gush Emunin who subsequently moved more politically leftward, incorporates the realia of geography, topography, history, and archeology. His Zakhor veShamor plays to his strengths and interests, as it explores the Jewish calendar and holiday cycle through the prism of the agricultural reality in the Land of Israel.

A duality runs through almost every chapter: God is both the Creator and also the God of history. He is responsible for both the stability of the natural order and the deviation from that order in miraculous salvation. The Jewish calendar and its holidays reflect this duality. Shabbat commemorates both creation and the exodus from Egypt. The three pilgrimage festivals each have an agricultural component and a historical one. R. Bin-Nun even finds an agricultural aspect to the Hanukka story. The dual solar-lunar calendar incorporates the regularity of nature (the solar cycle) and the novelty of God intervening in history (the lunar cycle). Though the moon also moves in predictable ways, we experience it as disappearing and reappearing, the term hodesh (month) conveys novelty and the Bible associates the lunar months with the exodus.

R. Bin-Nun offers interesting insights into specific holidays. Shabbat prohibitions related to the manna apply to work of the house (cooking); elsewhere, work out in the field becomes the focus (Exodus 23:12, 34:21). On Yom Tov, the second prohibition exists and the first does not. Bin-Nun creatively suggests that according to peshuto shel mikra the manna did not cease on Yom Tov and its halakhic implications apply only on the Sabbath.

Sukkot integrates the agricultural harvest festival with historical commemoration of our desert survival in booths. The first generates the mitzva to take the four species while the latter creates the commandment to dwell in sukkot. R. Bin-Nun associates the sacrificial order and its offerings of animals and produce with the creation/nature theme. Thus, the four species, unlike the booths, are associated with the temple. Biblically, we only take the four species for a full seven days “before God,” that is, in the temple.

Pesach must take place in the spring but it does not celebrate an agricultural component since we cannot yet enjoy the harvest. For R. Bin-Nun, counting the omer reflects trepidation about the upcoming harvest more than connecting the historical events of the exodus and revelation at Sinai. Like several predecessors, he explains that Pesach and Hag ha-Matzot are independent biblical holidays with the former beginning at midday on the fourteenth of Nissan and concluding twelve hours later. The latter is the seven-day holiday we currently call Pesach.

The Bible emphasizes the agricultural aspect of Shavuot and not the historical events commemorated on that day. R. Bin-Nun traces varying emphases though a history of the day’s Torah reading. The mishna (Megilla 4:5) indicates that we read Deuteronomy 16, which only contains the agricultural theme. The existence of a second day in the Diaspora and the need for an additional Torah portion for that day led us to add a reading about the revelation at Sinai from Exodus 19 (Megilla 31a). In antiquity, when Jews returned to the Land of Israel and one day of observance, they chose the latter reading, and the historical aspect gained dominance.

Yoel Bin-Nun

According to R. Bin-Nun, the twenty-fifth of Kislev had significance before the Hasmonean rebellion. Haggai prophesizes that from the twenty-fourth of Kislev and on, famine will give way to plenty (2:10-19). This timing has agricultural importance since the harvest of olives does not end at Sukkot time but continues towards the end of Kislev. This also explains why Hanukka is a relevant date for the mitzva of bringing the first fruits to the temple (Bikkurim 1:6). For R. Bin-Nun, this date became associated with the resurgence of the second temple and was purposely selected by both the Hellenizers and the Hasmoneans for their rededications of the mikdash. The illumination provided by olive oil and that time of winter in which the days get shorter until the solstice and then become longer establish light as a theme of the day prior to the Hanukka episode. Nature and agriculture become part of our winter celebration as well.

Given his love of the Land of Israel, his interest in farming and agriculture, and his commitment to Jewish independence, it is no accident that R. Bin-Nun remains profoundly uncomfortable with Purim. Esther represents the ultimate exilic book with its heroes bearing foreign names and its Jewish weakness encapsulated by the sentence “had we been sold for slaves and maidservants, I would have been quiet” (7:4). In his worldview, the Holocaust ended the exile and the historical relevance of Esther has come to a close.

During the two millennia of exile, Jews lacked a temple and did not engage in farming so we naturally focused on the historical elements of each holiday. Though this produced major lacunae in our religious experience, such historical consciousness enabled the miracle of Jewish survival through generations of persecution and migration. Along similar lines, R. Bin-Nun bemoans our inability to sanctify the new month by testifying about the moon’s reappearance, but also credits the fixed calendar with preserving unity for a globally dispersed Jewish community.

In the closing chapter, R. Bin-Nun relates to our current situation and our return to the land. He suggests novel rituals for Yom Ha’atzmaut (a seder with Torah readings and families telling their aliya stories) as well as bikkurim pageants. However, he is well aware that returning to the ancient world and biblical models is not a simple endeavor. In the modern economy, few people engage in farming so we are collectively not in rhythm with nature and the agricultural cycle. Many moderns find it difficult to identify with the yearning for a renewal of animal sacrifices. Finally, the temple should be a unifying institution which seems hard to imagine given the current divisions in Am Yisrael.

This work incorporates several striking ideas not connected to the general thesis which will have to wait for another time. We are fortunate to have R. Bin-Nun apply his fertile mind to scripture, Jewish history, and our current situation.

Yitzchak Blau, Rosh Yeshivat Orayta in Jerusalem’s Old City, is an Associate Editor of TRADITION.