Amen and A-Women

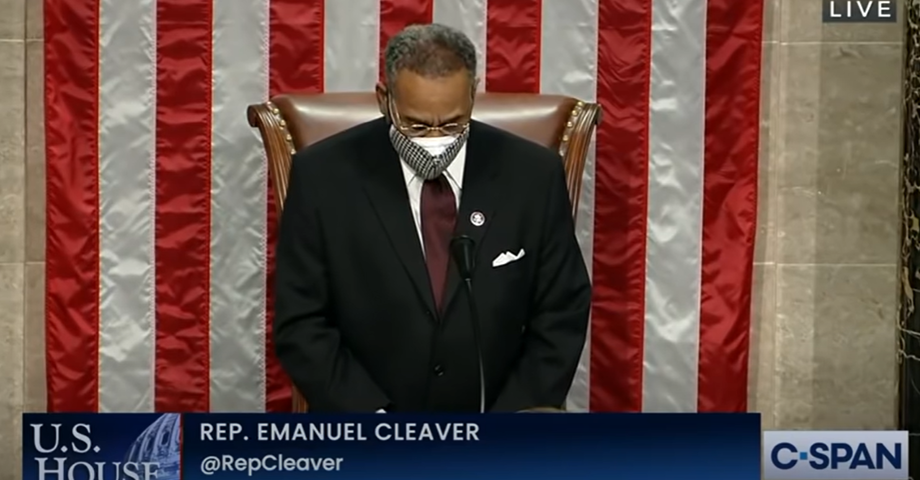

Many eyebrows were raised, and pearls clutched, at House Rep. Emanuel Cleaver’s prayer at the recent opening of the 117th Congress, which concluded: “Amen and A-woman.” Some claimed this was a case of exaggerated political correctness. Linguist John McWhorter, however, states that this phrasing was rather a “kind of witticism,” and has actually been used for decades, going back to the 19th century.

Many eyebrows were raised, and pearls clutched, at House Rep. Emanuel Cleaver’s prayer at the recent opening of the 117th Congress, which concluded: “Amen and A-woman.” Some claimed this was a case of exaggerated political correctness. Linguist John McWhorter, however, states that this phrasing was rather a “kind of witticism,” and has actually been used for decades, going back to the 19th century.

This episode became a learning moment about the word “amen,” as many who thought it was of Latin origin discovered that amen passed into English from Hebrew.

This last point, of course, is not news to anyone at all familiar with Jewish liturgy. But much less clear is how should we, those faithful to the sacred Hebrew language, view such modification as used by Rep. Cleaver? Are Hebrew words porcelain figurines, placed carefully on a shelf, or instruments that can be taken apart and put together anew at need?

This debate, often called prescriptivism versus descriptivism, is waged by linguists the world over. Because of Hebrew’s stature as the “Holy Tongue” it has been at the center of such debates perhaps more intensely than other languages.

One example of this dispute can be found in the Middle Ages. The word teruma is a noun that appears frequently in the Bible. But while the biblical verb associated with this mitzva is herim (as in Exodus 35:24 – kol merim terumat kesef, “whoever donated [raised up] gifts of silver”), in the Talmudic period a new verb was formed from the biblical noun – taram. The advantage of a new verb was that the existing verb herim, unmoored from its connection to tithing, came to mean more generally “to lift,” while the new verb taram took the specific meaning “to donate.”

This linguistic innovation was not welcomed by all medieval scholars. For example, Menahem ben Saruk (920-970) objected to it in his early dictionary, the Mahberet. But Maimonides defended this kind of innovation, writing in the introduction to his commentary on Masekhet Terumot:

[The rabbis] said, throughout the Mishna, taram, ve-turam, ve-yitrom. But modern linguists have difficulties with this, saying that the real words are heyrim, meyrim, and yarim. There is really no difficulty, however. The basic expressions of every language always derive from what was spoken by the people of that language and what was heard from them. [In this case], these are without a doubt the Hebrews in their land, that is to say the Land of Israel – for from these people one hears taram and all the verbal conjugations derived from it. This then is a proof that [such a thing] is possible in this language, one of the terms proper to those in Hebrew. This should be your answer to anyone who thinks, according to the moderns, that the language of the Mishna is not eloquent, and that [the Rabbis of the Mishna] created verbal forms that are not correct by using some words and not others. This principle I have told you about is quite well-founded among all established scholars who discourse on general matters pertaining to all languages.

Maimonides’ arguments against linguistic purity apply just as much today as they did to the “modern linguists” of his time.

However, Rep. Cleaver’s “a-woman” was not a new coinage, but more a word-play or pun. Should that be considered acceptable use of the Hebrew language?

For this, we need to go back to the beginning. The very beginning – in fact, the first words the Torah records having been spoken by a human. Following the creation of woman, the Bible reports: “Then the man said: This one at last is bone of my bones and flesh of my flesh. This one shall be called Woman (ishah) for from man (ish) she was taken” (Genesis 2:23).

At first glance, it would appear that Adam named the woman after himself, giving her name the feminine suffix -ah. However, the consensus of modern linguists is that ish and ishah are not cognates. Ish comes from the root אוש, and ishah derives from a different root – אנש. Evidence for the different roots can be found in the dagesh (diacritical dot) in the middle letter shin of ishah. That dagesh indicates the doubling of a letter that occurs when a weaker letter drops out of the word. In this case, the nun in the original root fell out.

It isn’t uncommon for the “n” sound to drop from words. In English we say “illegal,” and not “inlegal,” (from the Latin in-, meaning not legal) because the “n” would be difficult to pronounce. Hebrew has the same phenomenon, with examples including the future tense of nofel (fall) being yipol, and the nun missing from af (anger) showing up in the verb hitanef (to be angry.) Often, other Semitic languages will preserve the missing nun, and indeed there is an Aramaic word for woman, inteta which includes a nun.

Even some pre-modern linguists, such as Radak in Sefer HaShorashim (s.v. אנש), accept that ish and ishah aren’t etymologically related. If so, what are we to make of Adam’s statement that she should be called ishah because she was taken from an ish? Rashi’s commentary on that verse can help us. Quoting a midrash, he writes that “here we have a play on words [lashon nofel al lashon – literally, “one expression falls on another expression”], and from this [we can derive] that the world was created in the Holy Tongue.”

What is this “play on words”? R. Yitzhak Arama (Akedat Yitzhak, ch. 8) notes that ish and ishah aren’t related, and as such are different from words for animals where the female word is simply the male word with -ah added, like par (bull) and parah (cow). His proof is from that same midrash cited by Rashi. As he writes, it would not be lashon nofel al lashon if there was only one expression!

So it turns out that when Adam gave a name to his wife, in his very first recorded speech act, he made a play on words connecting the (unrelated) terms for man and woman. God included that pun in the Torah. To me, that appears to be reason enough to be flexible when Adam’s descendants use language similarly. May we all be comfortable enough in Hebrew to use it as a living language, amen.

David Curwin writes about the origins of Hebrew words on his Balasḥon Blog, and about Jewish thought in TRADITION and elsewhere.