REVIEW: America’s Book

REVIEW: Mark A. Noll, America’s Book: The Rise and Decline of a Bible Civilization, 1794-1911 (Oxford University Press, 2022), 848 pp.

Recent debates about President Biden’s student debt forgiveness initiative, in which many invoked parallels to Shemitta, highlight the continued centrality of the Bible in contemporary political and cultural discourse. The roots of this phenomenon trace back centuries in American history. Mark A. Noll’s new volume, America’s Book: The Rise and Decline of a Bible Civilization, 1794-1911, offers an authoritative synthesis of this story. An 848-page scholarly behemoth, America’s Book is the long-awaited sequel to Noll’s earlier work, In the Beginning Was the Word: The Bible in American Public Life, 1492-1783 (Oxford, 2015). While the latter spanned the colonial period to the American Revolution, America’s Book continues through the late eighteenth century, from Thomas Paine’s Age of Reason (1794-1795), to the tricentennial of the King James Bible translation in 1911. Noll argues that a Protestant “Bible Civilization” emerged in the early decades of the United States, fractured during the antebellum slavery crises and nascent religious diversity, and declined after the Civil War.

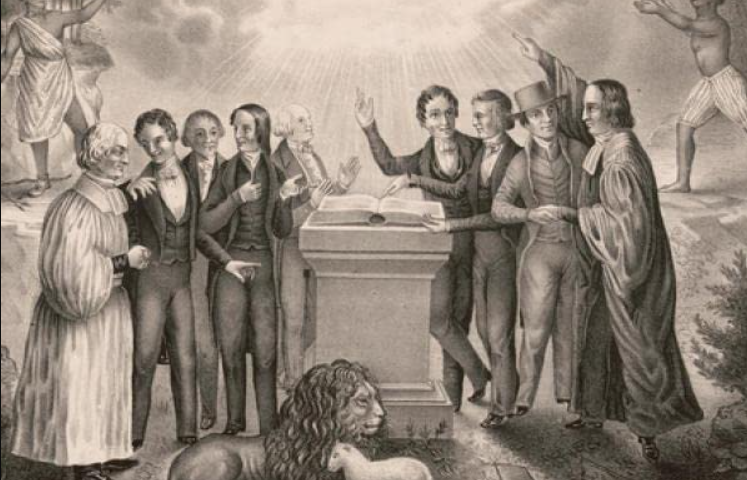

America’s Book proceeds both chronologically and thematically. Part I, “Creating a Bible Civilization,” begins with the postrevolutionary context, emphasizing the controversy surrounding Paine’s provocative challenge on the authority of Scripture. Noll puts forth a useful distinction between “custodial” Protestants, who sought the fusion of religion and public life, and “sectarian” Protestants who favored separation of church and state. Part II provides a thematic survey of the early national Protestant Bible Civilization, in which Scripture served as a unifying religious text; biblical personal, place, and institutional names abound at this time; and publishers produced over one thousand editions of the Bible between 1801 and 1840, making it the best-selling book of the period. Some of the statistics are truly astonishing: the American Bible Society, founded in 1816, launched a “General Supply” plan to send a Bible to the estimated 800,000 American families that did not own one already; from 1829-1831 the society printed 786,000 copies and distributed 638,000 of them. Part III, “Fractures,” resumes the chronology by tracing the breakdown of the Bible Civilization as the debate over slavery intensified. Both sides, as Lincoln famously observed in his Second Inaugural Address, marshaled the Bible to support their views on slavery. In a stunning example of intellectual candor, Noll retracts his earlier position that the pro-slavery advocates held the intellectual upper hand over abolitionists. Instead, he maintains, “the Bible in antebellum America, and understood in traditional terms, offered wider, deeper, and more thorough support for abolition than for slavery. Contingent historical circumstances, rather than the intrinsic credibility of the arguments, created the opposite impression.” This reversal reflects not only an important development in the historiography of American slavery and religion but also a useful reorientation in the way we view the Bible itself.

America’s Book proceeds both chronologically and thematically. Part I, “Creating a Bible Civilization,” begins with the postrevolutionary context, emphasizing the controversy surrounding Paine’s provocative challenge on the authority of Scripture. Noll puts forth a useful distinction between “custodial” Protestants, who sought the fusion of religion and public life, and “sectarian” Protestants who favored separation of church and state. Part II provides a thematic survey of the early national Protestant Bible Civilization, in which Scripture served as a unifying religious text; biblical personal, place, and institutional names abound at this time; and publishers produced over one thousand editions of the Bible between 1801 and 1840, making it the best-selling book of the period. Some of the statistics are truly astonishing: the American Bible Society, founded in 1816, launched a “General Supply” plan to send a Bible to the estimated 800,000 American families that did not own one already; from 1829-1831 the society printed 786,000 copies and distributed 638,000 of them. Part III, “Fractures,” resumes the chronology by tracing the breakdown of the Bible Civilization as the debate over slavery intensified. Both sides, as Lincoln famously observed in his Second Inaugural Address, marshaled the Bible to support their views on slavery. In a stunning example of intellectual candor, Noll retracts his earlier position that the pro-slavery advocates held the intellectual upper hand over abolitionists. Instead, he maintains, “the Bible in antebellum America, and understood in traditional terms, offered wider, deeper, and more thorough support for abolition than for slavery. Contingent historical circumstances, rather than the intrinsic credibility of the arguments, created the opposite impression.” This reversal reflects not only an important development in the historiography of American slavery and religion but also a useful reorientation in the way we view the Bible itself.

In Part IV, “The Eclipse of Sola Scriptura,” Noll carries forward his argument through the final decades of the antebellum era and the Civil War itself. Beyond the fractious dispute over slavery, Noll argues that the emergence of a wide variety of religious denominations and minority groups further diminished the authority of Scripture in American culture and politics. Catholics, who rejected the doctrine of sola scriptura (unlike Protestants, they believe in the validity of extra-Scriptural traditions such as the institution of the papacy), undermined Protestant hegemony by advocating against the King James Version; Jews sometimes joined these challenges. The distinctive traditions of German Lutherans, African Americans, and Native Americans also departed from the Protestant mainstream. The emergence of widespread atheism as well as academic biblical criticism repudiated Scripture entirely and relegated it to the realm of ancient history. In the final two parts of America’s Book, Noll traces the further erosion of the Protestant Bible Commonwealth after the Civil War, and he looks toward the present in his conclusion. Noll poses a thoughtful question: “How may Scripture be deployed to support the health of the body politic in a specific place without being reduced to a utilitarian tool of this-worldly interests and so lose its potential as a spiritual guide for all times and places?” Reflecting on the recent past, Noll remarks: “When the Bible shows up in the political sphere, it is usually as a weapon—frequently from the Right to advocate for policies defending traditional sexual mores, protecting traditional marriage, and speaking for unborn children, but also from the Left for advocating policies defending the poor, protecting abused women, and speaking for disadvantaged children at risk.” Nevertheless, Noll cites an extensive survey from the early 2010s, which found that a majority of Americans are more likely to use the Bible for personal prayer and devotion than partisan politics.

Three chapters of America’s Book should be of considerable interest to readers of TRADITION. Chapter 14, “The Common School Exception,” shows how the Bible surprisingly remained immune to the general trend of disestablishment in the early American republic. By 1833, every American state had finally ended taxation toward an official government church, but it remained legal in many states for public schools to mandate Bible reading. Courts often justified this practice on the grounds that the Bible is a “non-sectarian” text and useful for cultivating virtue. It is worth revisiting the history of the controversies and court cases regarding this practice. Many of the legal, moral, and constitutional arguments raised are especially relevant considering recent and ongoing developments such as this year’s Supreme Court cases Kennedy v. Bremerton School District and Yeshiva University v. YU Pride Alliance, which raise serious questions about the role of the state in controlling religious education. Additionally, chapters 17 and 26 devote sections specifically toward Jewish treatments of the Bible in the pre- and post-Civil War periods. While one might assume that the People of the Book would have outsized importance in a history of the Bible in America, Noll relegates Jews to a place alongside several other minority groups such as African Americans, Catholics, and Natives. Overall, Noll’s story is largely a Protestant one, but the balance of material is perhaps justified by the relative size of denominational populations and the undeniable influence of Protestantism.

One theme that runs throughout the volume is the tension between modern biblical criticism and traditional faith. It is noteworthy to see that Christians have been grappling with these questions in ways similar to discourse within Orthodox Jewish intellectual and educational spheres. Granted, belief in Torah mi-Sinai and unitary divine authorship is presumably less fundamental in a supersessionist framework that rejects much (or at least some) of the Mosaic revelation, but it is worth keeping in mind that the intellectual challenges we face today have much older precedents.

I have long admired Noll’s practice of self-disclosure regarding his own religious identity (he is a self-identifying Evangelical, and he has served on the faculty of Notre Dame). In his previous book, Noll warned about “slippage” between the personal and scholarly sides; here, he explicitly counts himself among those who are “guided primarily or even solely by the Bible.” This is perhaps a move that only a senior scholar such as himself can now afford to risk; as R. Shalom Carmy recently ruminated in a Lehrhaus symposium, “R. [Aharon] Lichtenstein, almost seventy years ago, and anyway not intending to make a career as an English professor, aggressively put his theological convictions on display in at least two crucial passages of his thesis on seventeenth-century Anglican writing. Would that be prudent today?” In Jewish studies especially, R. Carmy cautions, “Yirat Shamayim is liable to be corroded as the academic wannabe checks his or her emunot ve-deot at the door of the seminar room.” While self-disclosure of other identities is increasingly common in academic literature, my sense is that is not the case for religious scholars.

America’s Book stands as a monumental scholarly achievement, but it is also valuable for lay readers. All future scholars who study this subject will cite and rely upon America’s Book, and they will come to depend on its survey and synthesis of the primary sources, and for filling in and identifying important gaps in the existing scholarly literature. At the same time, anyone who wishes to better understand the trajectory of American religious history and the origins of today’s contested religiopolitical order would find it helpful to begin with this volume. Orthodox Jews in particular might find America’s Book useful for thinking through their place in questions about church-state relations.

My only quibble, completely unfair for a book of this length, is Noll’s decision to end the narrative in 1911. While he identifies the tricentennial of the King James Version as a logical endpoint, doing so omits the 1925 Scopes Monkey Trial in which the Bible (and its interpretation) nearly served as a litigant itself! Of course, a narrative of this length and scope must end somewhere, but perhaps a more natural stopping point would have been the Supreme Court case Abington School District v. Schempp (1963), which rendered school-sponsored Bible reading unconstitutional. That decision reflected the culmination of the process that, from a legal standpoint, severed the remaining vestiges of the Protestant Bible Civilization that Noll describes. While traces of the old order remain etched on our coins and courthouse walls, and Scripture retains its rhetorical, cultural, and literary influence, America after 1963 has been and will likely remain a decisively secular state.

The stakes of America’s Book are more than merely historical. Noll argues that the Bible not only was important in American history, but that it still is (though not in the same way and to the same extent), and that it should remain a source of wisdom and inspiration. “Christian and Jewish adherents of scriptural religion,” he remarks, “have not been wrong to think that democratic self-government requires virtues of the kind encouraged by biblical teaching.” His powerful final words deserve full citation:

From Christopher Columbus to the present day, the appropriation of universal scriptural values in American history has mingled constantly with its use for particular purposes, sometimes in keeping with those values, sometimes violating them with abandon. That mixed record must temper anything triumphalist Bible believers might say in its favor. Yet an honest assessment of the nation’s history, and at no time more than the present, should also recognize that a democratic republic needs something like the Bible more than Bible believers need a democratic republic.

Notwithstanding Noll’s optimistic outlook, I would like to add a word of caution to those who seek to mine the Bible as a political text for the 2020s. To return to the parallel of student loan forgiveness and Shemitta: The Bible does not neatly align with any political theory, position, or party. Rather, it is a complex and often contradictory collection of different ideas and genres, encompassing multiple periods of history. Cherry-picking an individual verse (whether from the Hebrew or Christian Bible) to score culture war points, on either side, cheapens Scripture. To borrow the Sages’ phrase, we should never instrumentalize the Bible as “a spade to dig with.”

Reception histories such as America’s Book illustrate that there is no one true meaning for the Bible. Each society appropriates and reinterprets it based on the questions and concerns of its time. I do not advocate for complete interpretive relativism; as a variant of the rabbinic adage goes, there are seventy faces to the Torah, but not seventy-one. Nor do I deny that Scripture can nevertheless provide us valuable moral teachings that should in turn inform our political sensibilities. For our part, we dare not use Tanakh solely to confirm what we think we already know. Orthodox Jews do not believe in Scripture alone; our Bible reading exists within the framework of the voluminous rabbinic tradition. In a sense, we believe in sola talmudica: the Talmud is the “Bible” of rabbinic Judaism. Individuals who wish to use Tanakh as a political text should also reckon with this broader literary canon and our interpretive traditions.

Yisroel Ben-Porat is a Ph.D. candidate in early American history at CUNY Graduate Center and Managing Editor at The Lehrhaus.