An End to this Year’s Curses

The Cycle of Jewish Holidays (Synagogue of the Suburban Torah Center, Livingston, NJ)

I was recently invited to a discussion group that aims to think about how we’ll shape anew—for this year at least—the prayers of the Days of Awe and holidays: which Tehillim to add, which customs to tweak, which prayers to supplement. I asked them to invite someone else. But they insisted. Apparently it’s important for them to hear what I think. I insisted as well: I don’t want to participate. Not because they are wrong. On the contrary, I’m sure they will come up with wonderful ideas that will be very suitable for certain communities. In all cases, I really don’t feel like telling them what I really think. But from you, gentle reader, I have no secrets—so here’s the truth. If it were up to me, I wouldn’t change a thing. Not one word should be added or subtracted from our liturgy.

My position does not emerge from conservative tendencies or a desire for everything to remain the same. Quite the contrary, because nothing can be the same anymore. I look into my Siddur or Mahzor like a child learning to pray for the first time. Zakhrenu le-hayyim—Remember us for life, O King who desires life; Hamol al ma’asekha—Have mercy on your creation; Avinu, Malkenu—Our Father and King, act for the sake of those who were slaughtered for your Holy Name. Each well-known phrase now requires new thought before it spills off the tongue. Countless new images run through my head, new tears come to my eyes. Reciting “A Psalm of David: The Lord is my light and my salvation—whom then shall I fear?” now requires a trigger warning. Can anyone remain unmoved imagining the last Jewish child in Auschwitz who said the “Ma Nishtana? How is this night different than all others?” Elie Wiesel wrote that the most daring and subversive text he heard in the extermination camps was the Kaddish, “Yisgadal ve-yiskadash—Magnified and sanctified may His great name be.” More than all the claims and complaints and question marks echoed the gap between these familiar words on the lips and the vacuum in the broken heart.

The poet Rabbi Elhanan Nir wrote, shortly after Simhat Torah, “Now like air to breathe / we need a new Torah.” At first I thought he meant that we needed new halakhot and updated words to replace the “old” Torah. But now I read the rest of his poem: “We need a new Mishna and a new Gemara / … and a new Rav Kook and a new Brenner / and a new Leah Goldberg and a new Yehava Da’at,” and understand that he wants to say that all the same books and all the same words themselves need to be written again from the beginning. There is a story by the Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges about a fictional Frenchman named Pierre Menard. Written as an imagined piece of literary criticism of Menard’s attempt in the 20th century to compose a new version of Cervantes’ early seventeenth-century Don Quixote. But instead of taking the general lines of the classic work and adapting them to contemporary reality, through careful preparation he arrives at a state in which he is able to authentically write the same words, in the exact same order, as they were written in Spain four centuries earlier. Nevertheless, despite being a word-for-word replica it is a completely new work, with a different message than Cervantes’ original. It becomes much deeper and more complex. Descriptions that were naive for Cervantes become ironic under the pen of Pierre Menard; truths that were once trivial now sound subversive. Its message for our moment: Consider how saying “Tikhle shana ve-kileloteha—Bring an end to this year and its curses!” as we close 5784 bears no resemblance whatsoever to having done so a year earlier. Same words; entirely different piyyut.

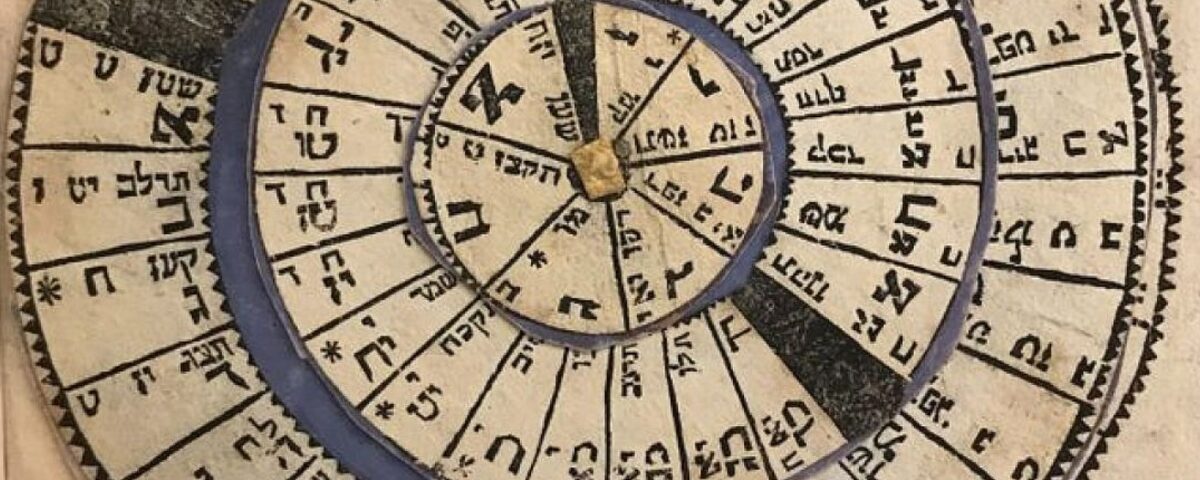

There is a unique halakha concerning a man mourning for his deceased wife, which forbids him to remarry before the passage of Shalosh Regalim—the cycle of three holidays. Understanding that the mourning process is not complete until he sits at the Seder table without her next to him, and celebrates Shavuot without her cheesecake, and sitting in a Sukka without her special touch at decorating it. What is unusual about this halakha is the fact that it does not depend on a fixed time. Depending on when she passed away it can be as brief as a bit more than six months, or sometimes almost a whole year. As for us, whose world was shattered last Simhat Torah, the cycle of the holidays was required to pass before we can try to move on. We lit Hanukkah candles when thousands of families were torn from their homes; celebrated Purim when there was no possibility to be truly happy; observed the holiday of freedom when hundreds of our children are in captivity. In my opinion, we don’t need any new piyyutim or prayers. We have a whole new calendar that will never be the same again.

Rabbi Avraham Stav teaches at Kollel Shaarei Zion in Yad HaRav Nissim, Jerusalem, when he is not serving in an artillery unit. This essay is adapted and translated from his column in Makor Rishon.