Book Review: Rabbi Levine’s Holiday Sermons

Book Review

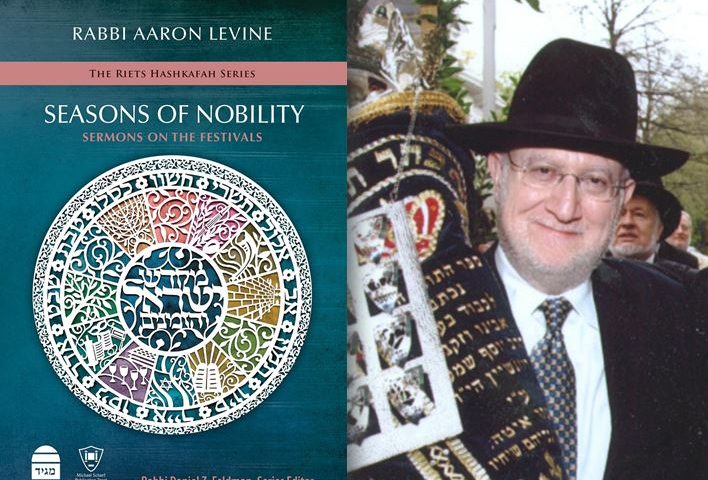

Rabbi Aaron Levine, Seasons of Nobility: Sermons on the Festivals (Maggid Books & Yeshiva University Press, 2019), 444 pp.

Reviewed by Elie Weissman

Asked to describe the ingredients for success in the sport of golf, 38 time champion Bobby Locke, pithily responded “You drive for show and putt for dough.” As a golfer his long drives often received the most attention, but it was his short game close to hole that won his championships. It’s the same for rabbinics. The very public, performative sermon with its flashes of eloquence and erudition garner much attention, but great careers are forged in the day-to-day trenches of pastoral care, halakhik research and counselling, and communal affairs. Rabbi Dr. Aaron Levine z”l made his admirable academic career in the field of economics and halakha. A long-time professor at Yeshiva University and a prolific author, Rabbi Levine distinguished himself as one of the foremost experts on the intersection of Jewish law and business ethics. His exceptional “short game” led to his appointment as editor of Oxford University Press’ Handbook on Judaism and Economics.

Seasons of Nobility, published by Maggid Press, posthumously collects Rabbi Levine’s holiday sermons, the expressions of his “driver” in short two and three pages essays. Touching on central themes of Rosh Hashana, Yom Kippur, Sukkot, Pesach, Shavuot, and even Yom HaAtzmaut, this eclectic work, mixing a broad array of source material, serves as a striking complement to Rabbi Levine’s career as a distinguished economist and ethicist, offers the reader some new perspectives on the holidays, and provides a valuable glimpse into the perspectives and personality of an noteworthy figure in Jewish American life.

Economics, as one might expect, figures prominently in a number of the sermons. Particularly of interest are his remarks upon Prof. Robert Aumann’s Nobel Prize in 2005. It was, Rabbi Levine notes, “the first time that the award was given to a person who is a deeply religious Jew and a first-rate Talmudist” (117). Rabbi Levine’s admiration for Aumann is apparent, but the creative comparison of Aumann’s game theory with the book of Kohelet is impressive. “Those who took up Aumann’s models said that if we start without conflict, whatever it is… if the relationship is an ongoing one, each participant will adopt strategic behavior and will realize that he or she can anticipate and affect what the rival will do” (118). For Rabbi Levine the point is cooperation and it smacks of the philosophy expressed in Kohelet’s fourth chapter that encourages cooperation as a way of building strength.

More than the details of economics, Rabbi Levine’s sermons shed light on the spiritual motivations for the ethical commitments he promoted. Speaking of the two loaves that one brings on Shavuot, he emphasizes the significance of “sanctifying the mundane” as the path to defeating the evil inclination that pushes us toward ethical missteps (323). The holiday becomes symbolic of commitment not only to the commandments that ask us to serve God, but the commandments that ask us to treat our friends and neighbors with respect. In a similar vein, Rabbi Levine justifies meticulousness in our care for others in a number of sermons. For Yom Kippur, he notes that the High Priest reads a portion of the Torah by heart in order to avoid tirha de-tzibbura. “It prohibits not only an action that will clearly demonstrate a contempt for the community, but also an action that will in a tolerable manner slightly cause some annoyance to one who is just a statistic for us at this point” (64). For Shabbat Hazon, he reminds that modesty leads to the sensitivity necessary to treat others with respect (352). The protective aspect of the Sukka relates to the responsibilities of tikkun olam (87).

Tellingly, the character of Aaron the High Priest arises a number of times in the work. Aside from sharing a name with the author, Aaron’s reputation as the rodef shalom, the pursuer of peace, fits seamlessly into the central themes of Rabbi Levine’s work. Aaron is the great Torah teacher who inspires others to greater commitments (78). Aaron brings the quality of kindness to an even higher plane than the forefathers (112).

Beyond the homiletical, there is a historical quality to these sermons as well. The work offers perspective on Rabbi Levine’s role as a community leader. On Sukkot of 1987, spurred by an act of arson at a local synagogue that destroyed five Torah scrolls, Rabbi Levine tackled a “new anti-Semitism perpetrated through the agency of children” (82). He defends Tisha B’Av from those who claimed it was an anachronism.

Throughout the work, Rabbi Levine reveals himself to be a great lover of Zion. “We stand now more than twenty years from the electrifying triumph of the Six-Day War. World Jewry basked then in a glamour, religious nationalism, and a sense of destiny” (211), he declared in1988. His Zionism leads Rabbi Levine to weigh in on some of the most controversial issues relating to the State: the settlements (93), the religious-secular divide (300), weaponry (108), and the state of Israel’s relationship with the world (356).

Rabbi Aaron Levine’s source material can only be described as eclectic. The text makes use of classical sources in the Talmud and Midrash, medieval commentators, gematria, Kabbalists, rationalists, and Hasidic rebbes. Its diversity makes Seasons of Nobility a valuable addition to the collected sermon genre. Indeed, the work opens the door into Rabbi Levine’s “long game” letting us know some of the creative philosophies of a great halakhist and ethicist.

Rabbi Elie Weissman has served as Rabbi of the Young Israel of Plainview since 2005, and teaches Talmud and Tanakh at Yeshiva University High School for Girls.