BOOK REVIEW: Faith and Freedom Haggadah

Faith and Freedom: Passover Haggadah with Commentary from the Writings of Rabbi Eliezer Berkovits, compiled and edited by Reuven Mohl (Urim Publications, 2019), 160 pp.

Reviewed by Yitzchak B. Rosenblum

Last year marked the 75th year since the liberation of Auschwitz and the end of the nightmare of the Nazi Holocaust. This horrific chapter in human history raised and continues to raise many significant questions about morality, justice and ethics, as well as the place of the Jewish people in the world. Even three-quarters of a century later, it seems the world still has not yet fully learned the lessons of the Holocaust, and apparently already forgotten others which we might have thought would have remained with us longer.

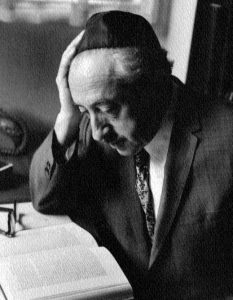

Rabbi Dr. Eliezer Berkovits zt”l was a leading theologian and talmid hakham who confronted the religious, moral, and philosophical implications of the Holocaust. A serious revisiting of R. Berkovits’ teachings started almost twenty years ago with the publishing of Essential Essays in Judaism which included 13 essays covering a broad spectrum of his teachings taken from his 19 books. Last year saw the republishing of his seminal work on this particular topic, Faith After the Holocaust. In this book, first published in 1973, he draws attention to the moral decay that led to the wholesale genocide of millions of innocents while the enlightened West watched from the sidelines, doing nothing. In it, R. Berkovits also explores and enumerates the challenges and failures of the world powers who, till today, continue down the road to amass military supremacy without considering the ultimate price we as a species may pay if we continue to ignore the message that God has been endeavoring to teach mankind through His Torah and His people.

Rabbi Dr. Eliezer Berkovits zt”l was a leading theologian and talmid hakham who confronted the religious, moral, and philosophical implications of the Holocaust. A serious revisiting of R. Berkovits’ teachings started almost twenty years ago with the publishing of Essential Essays in Judaism which included 13 essays covering a broad spectrum of his teachings taken from his 19 books. Last year saw the republishing of his seminal work on this particular topic, Faith After the Holocaust. In this book, first published in 1973, he draws attention to the moral decay that led to the wholesale genocide of millions of innocents while the enlightened West watched from the sidelines, doing nothing. In it, R. Berkovits also explores and enumerates the challenges and failures of the world powers who, till today, continue down the road to amass military supremacy without considering the ultimate price we as a species may pay if we continue to ignore the message that God has been endeavoring to teach mankind through His Torah and His people.

(Full disclosure: My wife Aliza is a granddaughter of R. Berkovits.)

It is this penetrating perspective that also engenders great relevance to R. Berkovits’ Faith and Freedom Haggadah. In it, the reader will benefit from the fruits R. Dr. Reuven Mohl has gleaned from masterfully examining R. Berkovits’ vast corpus to provide exceptionally prescient and timely lessons of his thought and elegantly place them in the familiar framework of the Haggadah, the classic text read at the Seder. If the goal of the night of Passover is to recount and re-live the events of the Exodus, reading this book shows, in some surprising ways, that reliving (and re-leaving) Egypt at the Seder carries with it many elements that mirror those of the Holocaust.

The central obligation of the Seder evening is to deeply examine the transition of the Jewish people from slaves to free individuals. The rabbis of the Mishna require each person to, “See themselves as if they themselves were taken out of Egypt” (Pesahim 10:5), and not merely reading the story of their ancestors from a far-away past. It is this unique aspect of the Seder that R. Berkovits’ philosophy matches in such a compelling fashion. His erudition in Tanakh, Talmud, Midrash, philosophy, and history is breathtaking in its scope and it reveals to the reader an insight into the relevance of the Hagaddah’s themes to contemporary Jewish life, thought, and continuity.

Having served as a rabbi in Berlin during the Nazi’s rise to power, he witnessed first-hand a civilized nation follow the path set out by Hitler as well as the complacency and silence of the West as millions of human beings were first excluded from civil society and ultimately marked for death. One cannot help but sense the parallels to the slow descent of the children of Israel into the oppression of Pharaoh’s Egypt which similarly started with a gradual and steady plan to mount a final solution to their Jewish problem.

As stated above, R. Berkovits thought is derived from the areas of classical Jewish sources, history, and philosophy dovetailing into what he refers to as “authentic Judaism.” The central facet is the engaging relationship between God and his chosen people and the role and responsibility of the latter to make His word known among the nations of the Earth, creating a world where all mankind lives together according to this elevated and enlightened mission. The path and process of history is central to R. Berkovits’ writings and is appropriately showcased by the carefully selected passages that the commentary culls in this Haggadah. In it, one can hear R. Berkovits’ passionate voice addressing issues that are so applicable to contemporary Jewish life. This strong tone emanates from his belief that Torah and halakha combine to form a cornerstone for the Jewish people to create a distinctive society and civilization that will shine a light unto the nations of the world. He identifies this as the challenge for the modern State of Israel, the culmination of two millennia of wandering the globe in darkness, often guided by the deep faith in the unseen hand of God and His promise of ultimate redemption. And it is with the format of the Haggadah that we are able to explore these essential lessons which transform the familiar ideas and themes in sharp and actionable teachings.

The scope of topics included in the Haggadah is as vast as it is relevant to the contemporary reader. This aspect is all the more significant in that many of the salient ideas were written in the midst of the Holocaust’s fury. In reading the selections one will discover over thirty discrete topics that range from holiness, Jewish education, the nature of being the chosen people, the essence of God and His hand in the universe, prayer for the Messiah. Each entry illuminates for the reader an essential lesson from the Haggadah and transforms that particular passage into a deep and inspiring idea that enables the reader to appreciate the teaching on a more profound level. For example, Mohl cites a passage to elucidate the recitation of Kiddush, “And exalted us above all tongues ” – something with which the observant Jew is so familiar and well-versed and possibly might underappreciate. Quoting R. Berkovits’ words from Towards Historic Judaism written in 1943, the reader will discover the importance of the Hebrew language as a key to penetrating the message of the Torah and its’ many teachers:

The Jewish School, in order to achieve its purpose, must introduce our youth to the world of Jewish thought. But this world is essentially Hebraic and the only key to it is the Hebrew language. Without a knowledge of Hebrew we can give our children only second or third-hand Judaism, one that has gone through shallow channels of translation, losing its vigor and luster in the process. Hebrew is not a mere technicality, the mastery of which gives us the luxury of being able to enjoy the original. It is an essential part of the expression of the Jewish spirit (25).

The theme of rabbinic leadership is to be found in the portion discussing the Sages and their obligation to plumb the depths of the Exodus’ story although they have already mastered it in detail. Quoting a section of Jewish Women in Time and Torah, R. Berkovits’ last book, we are given a description of the type of talmid hakham required in the modern era.

We need rabbis who are talmidei chachamim (talmudic scholars) with an adequate worldly education, who are seriously concerned and troubled by the inadequate regard for the problems of contemporary Jewish religious life, whose sense of rabbinical responsibility will give them the courage to speak out (46).

The Haggadah uses the classical midrashic style in its extrapolation of halakhot and derashot from various texts in Tanakh. To the uninitiated, this format can seem rather foreign and even confusing. It is with a greater familiarity with the “style” of Torah She’Be’al Peh that the participant will be able to appreciate the beautiful relationship between the written and oral laws. To emphasize this idea, Mohl quotes a passage from Crisis and Faith:

Only the Oral Torah, alive in the conscious of the contemporary teachers and masters who can fully evaluate the significance of the confrontation between one word of God and another in a given situation, can resolve the conflict; with the creative boldness of the application of the comprehensive ethos of the Torah to the case. Thus, Torah SheBe’al Peh, as Halakha, redeems the Torah SheBikhetav from the prison of its generality and “humanizes” it. The written law longs for this, its redemption, by the Oral Torah (51-52).

Those familiar with R. Berkovits’ main theological concerns will not be surprised to discover that the key themes which are examined most frequently are God, prayer, the State of Israel, and the Messiah. Indeed, the Haggadah commentary wisely provides copious annotations as well as a comprehensive bibliography. These four topics are central to his thought, connected as they are to the existence and historical journey of the Jewish people. The relationship among these four constitute the “DNA” of the trajectory and destiny of the Jewish people.

The first two form the spiritual, moral and educational relationship between God and His people. To live the deep life of Judaism, one must have a strong grasp of God and how He engages with man. While this is philosophically challenging, R. Berkovits faces it head-on. Commenting on the beloved Dayeinu section of the Haggadah, Mohl sensibly sees its connection to one of God’s names: Shaddai, “He who said ‘di,’ enough.” Quoting God, Man and History:

One sees the Talmudic version of this thought in the interpretation of the meaning of the divine name, Shad-dai. According to Resh Lakish, the name is a contraction of an entire phrase which maintains “that – in the act of creation – He called to the world enough!” Without that command, the world – as the result of the mightiness of the creative act –might have become limitless. See Talmud Bavli, Hagigah, 12a. But since the world did not create itself, God must have given the command to limit the work of creation to Himself. We see this in the interpretation of the Talmudic version of creation as an act of divine self-limitation (74-75).

Also, as expressed in God, Man and History, the connection between the Jewish historical past and the living present which is also at the core of the educational/experiential mission of the Seder night:

The revelation at Sinai never belongs to the past; it never ceases to be. It is as if the divine Presence, never departing from the mountain, were waiting for each new generation to come to Sinai to encounter it and to receive the word. Judged from the aspect of God’s relationship to Israel, as revealed at Sinai or in the exodus from Egypt, these encounters are ever-present events. The miracles and the signs, the thunder and the lightning are gone; but not God, or the message, or Israel. And so it is for the eye of faith to see what has been withdrawn from the senses, and for the ear of faith to hear, notwithstanding the silence (God, Man and History, 44).

When preparing to sing Hallel, the great song of God’s praise, we are called to consider the source of God’s greatness in a passage from Man and God:

Hashem is high above all the nations and above the heavens. But it is not for that that Hashem is being praised. He is being praised for no one is like unto Him – but not in what he is, being enthroned on high, but for what He does being enthroned… Even though He is highly exalted in His being, yet in his action He joins the poor and needy whom He raises up from the dust. Notwithstanding the transcendence of His being, He heals the barren womb that yearns for a child. This is what establishes God’s “name” (90).

Eliezer Berkovits

Prayer comes to the fore as a concrete affirmation of God-awareness. As quoted from Prayer, “The Jew, however, prays in acknowledgment of man’s absolute dependence of God; he prays for understanding in the realization that all human understanding is from God; he prays for the daily bread and the daily health, knowing that whatever his share may be, it is granted to him by God” (102).

The second two, the State of Israel and the Messiah, represent the culmination of God in history. The government of the Jewish people living in their ancestral land demonstrates to the nations of the world that human affairs can be conducted by a moral power rather than a military one (see Faith After the Holocaust, 142-143) in a place where faith is translated into historical reality (ibid., 136-137). The story of the Exodus which is re-lived at the Seder is the template for this dynamic of redemption where God reveals Himself and enters the world of human affairs to expose the bankruptcy of Pharaoh’s power politics in favor of the sanctity of the individual as reflected in God’s morality and maintained through His words.

One of the key elements of the story of the Exodus is the germination of the Jewish people’s awareness of God through the birth of their faith. That faith was intended to be transmitted from generation to generation as a call to action. R. Berkovits writes, “As a rule, religions do not make nations. Nations and peoples are biological, racial and political units… Israel alone is a people made to fulfill a God-given task in history; the people whom, as Isaiah expressed it, God ‘formed’ for Himself” (Faith After the Holocaust, 150).

The history and the journey of the Jewish people have constantly and consistently intersected with the great dynasties and kingdoms of humankind. This fact is repeated over and over both in Tanakh and the Talmud. A central question that emerges from this fact is, “Why?” Particularly in light of the disproportionate amount of suffering and loss heaped upon this tiny people that, how could they possibly pose a threat so that they were targeted and attacked in a manner similar to their ancestors in Egypt? Internally, Jews must ask themselves as well, “What is the purpose for all this suffering and what shall be our reward?” R. Berkovits beautifully addresses this issue in light of what the Messianic era will offer, not only to the Jewish people but to humanity:

A vital aspect of Jewish messianism is the faith in Israel’s return to its ancestral land. All the prophets that prophesy Israel’s redemption see it materialize in the land of Israel. God comforts Zion through the return of her children. Nothing could be further from the truth than to interpret these messianic hopes as a national aspiration. The prophetic mood belies such misconceptions. The messianic goal is a universal one. The Messiah ushers in universal justice and world peace. But the universal expectation is inseparable from Israel’s homecoming. The very passage that directs man’s hope to the time when, “Nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war anymore,” also envisages that, “Out of Zion shall go forth Tora, and the word of the eternal from Jerusalem” (Faith After the Holocaust, 145-146).

This perspective injects even more significance, theological and practical, into the crescendo of the Seder night, “Next year in the rebuilt Jerusalem!”

If the Seder is an experience of remembrance and rededication, then the words of R. Eliezer Berkovits, a witness to some of the most dramatic vicissitudes in Jewish history, including the Holocaust and the establishment of the State of Israel, will elevate that experience. It will provide new perspectives and appreciations of the beautiful words of the Haggadah.

Rabbi Yitzchak B. Rosenblum is a senior Judaic studies faculty member and college advisor at the Yeshivah of Flatbush Joel Braverman High School and the spiritual leader of the Young Israel of West Hempstead Early Childhood Center Minyan.

1 Comment

[…] service for the English reader by compiling R. Berkovits’ thoughts on the Passover Haggadah, Faith and Freedom, and now on Megillat Esther in his Faith […]