Eikha’s Lonely City

If a city could be lonely, it would be ancient Jerusalem after its destruction. The first verse of Eikha unspools the increased isolation of Jerusalem without mentioning it by name: “Alas! Lonely (badad) sits the city once great with people! She that was great among nations is become like a widow. The princess among states is become a forced laborer” (Lam. 1:1). Rashi, explains that a city that dwells alone is one that exists without inhabitants. The streets are abandoned. The buildings are derelict. All that remains are memories of Jerusalem’s former royal grandeur. Isaiah also offers us a portrait of lonely cities: “Thus fortified cities lie desolate, homesteads deserted, forsaken like a wilderness; there calves graze, there they lie down and consume its boughs” (Is. 27:10). Animals roam freely where humans used to live. Isaiah conjures an image of slow-moving cows chewing lazily in the ruins of a walled city; the hustle and bustle of commerce is replaced with overgrown vegetation as if no human ever occupied the space.

Eikha’s repeated references in the first chapter to states of female vulnerability enhance the portrait of exposure, defenselessness, and solitude. At night, a time of natural seclusion, the princess cries alone: “Bitterly she weeps in the night, her cheek wet with tears. There is none to comfort her of all her friends. All her allies have betrayed her; they have become her foes” (Lam. 1:2). Jerusalem is not only alone because enemies have sought her ruin; those she thought were friends have disappeared. Those who hate her have made her into “a mockery” – her former admirers see only her disgrace (1:8). Her shame is a bloodstain that all can see: “her uncleanness clings to her skirts” (1:9). She is a pariah. She sits with no one. She is loved by no one. She reaches out for help and company then withdraws: “Zion spreads out her hands;

she has no one to comfort her” (1:17).

Rashi, on the opening verse, however, tries to comfort us with a rabbinic citation that the city’s loneliness is only temporary. Rabbi Yehuda reads the first verse’s comparison of the city to a widow – ke-almana – as like a widow but not an actual widow. She is like a woman whose husband has gone overseas with every intention to return (Sanhedrin 104a). The separation is only temporary, but the time apart has created a sense of anxiety and loss soon to be mitigated when the husband comes home.

In R. Yehuda’s more optimistic reading the husband is a stand-in for the city’s residents, who will soon return and rebuild Jerusalem. He may also be using the couple’s separation as a theological metaphor for God’s abandonment of the holy city. The exile of the divine presence, the sage assures us, is only momentary within the broader framework of Jewish history. God, too, will return home. Rava’s interest in the same Talmudic passage, however, focuses us on the end of the verse. “Great among nations” is a description of Jewish diasporic influence: “Every place they [the Jewish people] go when exiled among the nations, the Jewish people become princes to their masters because of their wisdom.” One sage relieves us of long-term exile while another assures us of our success there.

Yael Ziegler notes the appearance of the word “kol” (all) twice in Eikha 1:2 “to convey the comprehensiveness of Jerusalem’s isolation.” It appears an additional 14 times in the span of 22 verses signaling an engulfing loss: “This portrait of catastrophe illustrates the seeping inclusiveness of Jerusalem’s downfall: her total isolation, misery, defeat, suffering, betrayal, loss, and humiliation” (77).

The lingering solitude so tenderly depicted in Lamentations, no matter how it is interpreted in the Talmud, coheres with a more ominous biblical loneliness that is by its nature existential. It is not one we will ever shake. Balaam the foreign prophet shares an observation from his high perch: “There is a people who dwell apart (le-vadad), not reckoned among the nations” (Num. 23:9). Was this an observation at the time or a prediction for the course of Jewish history? Our lonely city in Eikha is a constituent part of a lonely nation. Like Leviticus’ leper who must live alone (badad) outside the camp (Lev. 13:46), we will always collectively stand outside the mainstream camp of nation-states, our uniqueness turned into an ugly branding.

Today there is a haunting sense that the answer to this question is not merely a matter of biblical hermeneutics; it is a matter of pikuah nefesh, of life and death. Bernard-Henri Lévy entitled his latest book Israel Alone. Its cover shows a slice of light across a Jerusalem street; the rest is a desert scape in the muted color of midnight. “The Jews,” he writes, “are more alone than they have ever been.” He explains this solitariness:

There is nowhere in the world where Jews are safe; that is the message. No land on this planet is a shelter for Jews; that is what the Event of October 7 proclaims. Never and nowhere will it be possible to say that Jews can live in the world the way the French live in France, the English in England, and the Americans in America—and that will be true until the end of time: such is the obvious truth (25).

Lévy, like the prophet Balaam, believes our fate as a lonely nation is inescapable. Bret Stephens in his review of Lévy’s book for Commentary magazine agrees that post-October 7, even Israel is not safe for Jews but thinks Levy overstated his argument. “Lévy is suggesting that what might have died on October 7 was the conviction that Zionism still provided the best answer to the Jews’ most pressing problem—the need to survive.” Jews are at risk everywhere, “and the solicitude that Gentiles feel for our plight seems to be diminishing, everywhere.” We are, like the scorned maiden of Eikha, alone in the narrow straits.

This aloneness is condemnatory when forced from the outside, but to some it has been transformed into an internal source of creative energy and distinctiveness. If you cannot be safe anywhere, if you cannot be loved anywhere, then you might as well be anything and be everywhere. It is time to relinquish the self-consciousness that has straightjacketed our people from time immemorial. This valorization of Jewish distinctiveness that emerges from loneliness may be credited in part to Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik’s well-known confession of loneliness as it was framed 60 years ago in the pages of TRADITION. Initially in “The Lonely Man of Faith,” the Rav describes that his loneliness produced an almost orphan state of seclusion from the world despite enjoying the blessings of friends and family: “And yet, companionship and friendship do not alleviate the passional experience of loneliness which trails me constantly. I am lonely because at times I feel rejected and thrust away by everybody, not excluding my most intimate friends, and the words of the Psalmist ‘my father and my mother have forsaken me’ quite often ring in my ears.” We are struck by the language of alienation until the Rav later adds an addendum: “on the other hand….” It is then that we begin to understand how loneliness served him: “I also feel invigorated because this very experience of loneliness presses everything in me into the service of God.” He describes God in, “His transcendental loneliness and numinous solitude,” and one senses that the two are in the good company of each other.

An abiding sense of alienation can potentially promote a deeper relationship with God and self. Stripping away the noise of other people and the distractions of sociability and community yield a more perfect, less messy faith commitment. But now, so very long after October 7, I find myself wondering if loneliness can ever contribute to an optimal religious mindset or if we should all be more worried about the high costs of unwanted solitude.

“Loneliness,” writes social neuroscientist John T. Cacioppo “becomes an issue of serious concern only when it settles in long enough to create a persistent, self-reinforcing loop of negative thoughts, sensations, and behaviors” (7). The chants, the encampments, the leering and yelling at sports games and music festivals, the social media chatter, and the political game playing have created the persistent, self-reinforcing loop of negative thoughts, sensations, and behaviors. It is certainly, in Cacioppo’s words, an issue of serious concern for us now. And it comes as the world is realizing just how lonely it is.

Today there’s Loneliness Awareness Week, and both the United Kingdom and Japan have appointed Ministers of Loneliness. A poll conducted by the American Psychiatric Association in 2024 found that 30% of adults say they have experienced feelings of loneliness at least once a week over the past year, while 10% say they are lonely every day. Younger people are more likely to experience these feelings, with 30% of Americans aged 18-34 saying they were lonely every day or several times a week. Single adults are nearly twice as likely as married adults to say they have been lonely on a weekly basis over the past year. In The Lonely Century, Noreena Hertz writes extensively on the impact of loneliness on physical health.

A recent Harvard Business Review cover article cites an alarming Gallup poll: 1 in 5 employees worldwide is lonely at work. Cars, television, phones, gaming, and the privatization of American leisure time led Derek Thompson to the conclusion that the individual preference for solitude is “rewiring America’s civic and psychic identity” in his essay for The Atlantic, “The Anti-Social Century.” How might we relieve ourselves of this epidemic? AI. Paul Bloom, who calls loneliness a toothache for the soul shares current research in an essay for The New Yorker showing that chatbots and Therabots have proven to be empathic listeners, sought out for validation and advice when there is no one else to talk to. “Often you need a person, and sometimes you just need a hug. But not everyone has those options,” Bloom observes.

And just as our ancient Jerusalem was once lonely, there is today a global and national index of lonely cities. More than 37 million people live alone in the United States, about 29% of all American households, according to research conducted by the US Census Bureau. Researchers from the Chamber of Commerce used data from more than 170 cities to determine the top ten loneliest cities in the United States. Washington, D.C. is America’s loneliest city for the second year in a row. Internationally, a Google Trend survey identified Dublin as one of the world’s loneliest cities along with Perth and Sydney. In Stockholm, 58% of residents live alone. Aging, commuting, large scale migration, and social isolation brought about by COVID are all factors. The scale of this plague of loneliness is chilling.

This was of great concern for Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, who devoted a chapter to it in his last published book, Morality: “Loneliness, the sensed lack of human connection, touches on our essence as social animals. We are not the only such animals, but it is our ability to form extensive networks that differentiates us from other species. Our sociability is our humanity, and this is deeply rooted in our evolutionary past.” When these bonds break down, according to R. Sacks, essential human functions deteriorate. He was profoundly troubled by the impact of loneliness on the defining institutions that confer individuals with dignity and collegiality: “individualism comes at a high cost: the breakdown of marriage, the fragility of families, the strength of communities, the sense of identity that comes with both of these things, and the equally important sense that we are part of something that preceded us and will continue after we are no longer here” (29).

We are tasked with fighting the loneliness, not accepting it as either a broad social norm or an acceptable Jewish reality. God, not Adam, observed that it is not good for humans to be alone. We are created to be in the presence of others, to emerge from self-absorption to serve others, and to live in communities of compassion where we can see beyond ourselves. When it comes to our place in the world Stephens questions Lévy’s bleakness:

[T]he picture Lévy paints in Israel Alone is too dark. It ignores the dogs that didn’t bark in the night—the virtual absence of anti-Israel protests on the vast majority of university campuses outside of Berkeley, Stanford, Columbia, Harvard, Cornell, and a handful of other schools. It ignores the support Israel did get….We continue to have millions of friends and admirers, at home and abroad. Israel maintains an astonishing capacity to persevere through trials that would have broken weaker nations. Israel’s weaknesses were exposed on October 7, but more so were the weaknesses of its enemies…. Perhaps most important, an ancient Jewish instinct for danger, dormant too long, has been reawakened.

The hate is there, to be sure. But the love and support is visible as well. We have been awash in a cesspool of antisemitism since October 7. Jewish parents have raised alarm bells at the slightest insult. Organizations have mushroomed to combat antisemitism. Throwing money at it will not make it go away. But all this amplification did accomplish something: it cemented a narrative of isolationism that has made us more lonely, not less. Instead of investing in Jewish literacy, in building sacred communities, and in bridging distances, we have taken a megaphone to hate and raised a suspicious generation. We risk betraying Isaiah’s mandate to be a covenant people to the nations when we despise them for despising us. David Ben-Gurion famously said: “Our future does not depend on what the gentiles will say, but on what the Jews will do.” What will we do to shape the narrative differently instead of being its victim? Rabbi Sacks writes of his epiphany that Balaam’s statement of Israelite isolation shows “how dangerous this Jewish self-definition had become. It seemed to sum up the Jewish condition in the light of antisemitism and the Holocaust.” It was not a blessing but a curse: “To be a Jew is to be loved by God; it is not to be hated by Gentiles.”

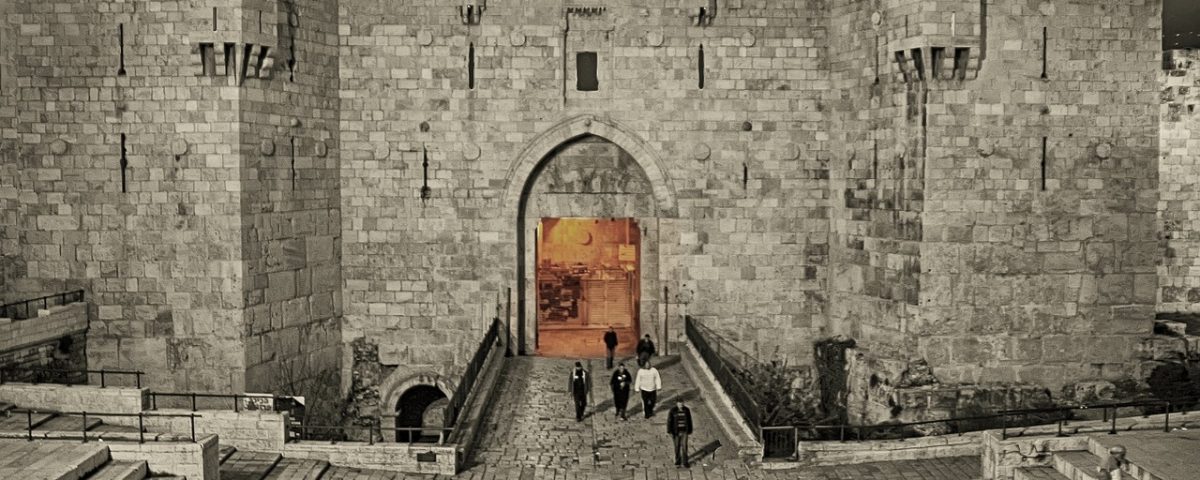

Jerusalem is not lonely. It has never been less lonely. It is hard to find one desolated corner in the entire city. Jeremiah would walk it streets in astonishment. Balaam was a prophet, but he was not our prophet. In these Three Weeks, let us recall our loneliness. Let us not relive it.

Dr. Erica Brown, consulting editor at TRADITION, is the Vice Provost for Values and Leadership at Yeshiva University and the founding director of its Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks–Herenstein Center for Values and Leadership.

1 Comment

I believe Dr. Erica Brown is too optimistic about anti-Semitism on North American and British campuses. The mailings I receive from the Anti-League, from alumni and students at MIT, not one under President Trump’s own campaign like Harvard and Columbia, show me a darker picture. And I fail to understand why the Western Jewish Community does not use the facts about the relationships of Arabs and Jews, from the time of Muhammad on, particularly in the Holy Land, to counter the lies taught in the universities and colleges that have sparked the increase in anti-Semitism for close to a half-century, This is my own personal loneliness, seeing the problem and one element of its solutions without response from my own former teachers and friends. But the Jerusalem Yeshiva where I study has teachers and students that do understand, and that makes life tolerable for a 93-year-old that considers every morning to awake and function as another miracle.

David Lloyd (ben Yaacov Yehuda) Klepper