Looking Backward: Talmud la-Talmida

Looking Backward: Talmud la-Talmida

Warren Zev Harvey

For my five-year-old granddaughter, Lia Sivan

One evening this past fall I received an email from Jeffrey Saks, the new editor of TRADITION, asking me to write a “Looking Backward” piece revisiting my 1981 essay, “The Obligation of Talmud on Women According to Maimonides” (TRADITION 19:2, Summer 1981). Replying immediately, I apologized politely that “I haven’t considered the subject in more than three decades,” and “the only reason I broached it then was that I was very much concerned about my little daughter’s education.” My essay was part of a long and tough battle to assure that she received a good education in Talmud. Indeed, I had prefaced the article with the dedication: “For my five-year-old daughter, Noa Eve.” I was thus right on the verge of giving a negative reply to Rabbi Saks, when suddenly I had a second thought, and did an about-face.

“However,” I continued, “I suppose it’s time I returned to the subject, since my daughter Noa has a five-year-old daughter of her own, Lia Sivan, and I must worry now that she gets a good Talmudic education, as her mother did.”

Saks wrote me back right away: “Excellent! What perfect timing! You’ll be revisiting the essay exactly one generation later.”

The following are some brief reflections on my now nearly forty-year-old essay and its repercussions. In the course of my reflections, I will ask: How much has changed between the time of my daughter Noa’s fifth birthday and that of my granddaughter Lia?

The Tosafists vs. Maimonides

Shortly after the essay appeared in TRADITION, I received a telephone call from Rabbi Leon M. Mozeson, a noted student of Rabbi Dr. Joseph B. Soloveitchik, who had taught at Maimonides School in Brookline, MA, during the 1960s. He got right to the point. “Rabbi Soloveitchik,” he said, “didn’t rule like the Rambam regarding Talmud and women, but like the Tosafot.” “What does that mean?” I asked.[1]

The alleged prohibition of teaching women Torah, Rabbi Mozeson explained, is based on the dispute between Ben-Azzai and Rabbi Eliezer ben Hyrcanus recorded in Mishna Sota 3:4. Ben-Azzai taught: “A man is required to teach his daughter Torah, so that if she drinks the bitter water [Numbers 5:11-31], she will know that merit suspends punishment.” Rabbi Eliezer taught on the contrary: “Anyone who teaches his daughter Torah teaches her lasciviousness.” Maimonides ruled according to Rabbi Eliezer (Hilkhot Talmud Torah 1:13).

However, there is good reason to think that Rabbi Eliezer’s dictum was only his own personal opinion (daʿat yaḥid), and not shared by other Rabbis. Thus, in Sota 21b, it is asked: “What is Rabbi Eliezer’s reason [for prohibiting the teaching of Torah to women]?” It is explained that he relied on the verse, “I, wisdom, have made subtlety [ʿormah] my dwelling” (Proverbs 8:12), which he took to mean: “When wisdom enters a person, subtlety [ʿarmumit] enters with it.” The Talmud then asks: “But what about our Rabbis?” How do they interpret the verse? It is answered that they take it to mean that “words of Torah are sustained only in someone who makes himself naked [ʿarum] for them.” From this exchange, it appears that Rabbi Eliezer’s view was not shared by “our Rabbis,” but was only his personal opinion.

Evidence concerning Rabbi Eliezer’s view is found also in Yerushalmi Sota 3:4,18d-19a (cf. Ḥagiga 3a). It is stated there that “Ben-Azzai is not like Rabbi Eleazar ben Azaria.” R. Eleazar ben Azaria is said to differ from him by virtue of his comment on the verse: “Assemble the people, the men and the women and the children… that they may hear and may learn… and observe to do all the words of this Torah” (Deuteronomy 31:12). He comments: “If the men come to learn and the women to hear, why do the children come? To give reward to those who bring them.” According to one reading, R. Eleazar ben Azaria disagrees with Ben-Azzai on the question of whether women may study Torah: he holds that they may not “learn,” but only “hear.” However, according to a second reading, R. Eleazar ben Azaria agrees with Ben-Azzai that women may study Torah, but differs from him only concerning the reason: he holds that they do not study in order to know that “merit suspends punishment,” but rather to “observe and do all the words of this Torah.” If the second reading is accepted, then R. Eleazar ben Azaria agrees with Ben-Azzai that women may study Torah, and Rabbi Eliezer’s prohibition remains nothing but his own personal opinion.

The first reading is apparently upheld by Maimonides, who affirms Rabbi Eliezer’s prohibition. However, the second reading is explicitly upheld by the Tosafists, Sota 21b, s.v. Ben-Azzai omer: “It seems that he [Rabbi Eleazar ben Azaria] interpreted [Deuteronomy 31:12] such that the commandment to let the women hear [the Torah] is in order that they know how to perform the commandments, and not because they should know that merit suspends punishment” (see Rabbi Moses Margolies, Penei Moshe, on Yerushalmi Sota, ad loc.; but cf. Tosafot, Ḥagiga 3a, s.v. nashim).

Maimonides’ prohibitory view is codified by Rabbi Joseph Karo, Shulḥan ʿArukh, Yoreh Deʿah, 246. However, Rabbi Moses Isserles (Rema) adds a gloss: “In any case, a woman is obligated to study the laws that concern women.” Is this gloss to be understood as merely a minor corrective to the rulings of Maimonides and the Shulḥan ʿArukh, or is it a complete rejection of their rulings and an adoption of the view of Rabbi Eleazar ben Azaria as understood by the Tosafists? An authoritative answer to this question is given by Rabbi Elijah Gaon of Vilna, who explains the comment of Rema by citing the Tosafot on Sota 21b (Biurei Ha-Gra, Yoreh Deʿah, 246:26). In short, Rema rules here with Ben-Azzai and the Tosafists, not with Rabbi Eliezer and Maimonides (cf. also Rabbi Zadok Ha-Kohen of Lublin, Otzar ha-Melekh, Hilkhot Talmud Torah 1:13, who gives an argument that Rema follows Ben-Azzai). Since the rulings of Rema are generally binding for Ashkenazi Jews, it follows that for Ashkenazi Jews there is no prohibition at all concerning the teaching of Torah to women.

At the Maimonides School in Brookline, MA, ever since it was founded in 1937 by Rabbi Soloveitchik, Talmud has been taught equally to boys and girls. According to Rabbi Mozeson’s report, Rabbi Soloveitchik ruled in this egalitarian way because he followed here the Tosafists, Rema, and Vilna Gaon, and not Maimonides and the Shulḥan ʿArukh.

Maimonides: Interpreted or Bypassed?

In my essay I sought to interpret Maimonides. I argued that while he sets down a prohibition concerning the study of Torah by women within the framework of the commandment of talmud Torah (Hilkhot Talmud Torah 1:13), he obligates women to study Talmud within the framework of the five commandments of the Pardes (Hilkhot Yesodei ha-Torah, chaps. 1-4). I conjectured that his prohibition concerned the study of the Torah as legal science, while his obligatory ruling concerned its study as wisdom.

However, Rabbi Mozeson had now informed me that according to Rabbi Soloveitchik we have no need to interpret Maimonides on the question of Talmud and women. Rabbi Soloveitchik has a more radical solution. Maimonides is bypassed.

The Woman and Halakha

In December 1986, the Orthodox feminist Pnina Peli (d. 2006) organized an international conference in Jerusalem on “The Woman and Halakha.” I gave a talk there on the position of the Tosafists on the question of Talmud and women. I tried to develop in detail there the halakhic approach I had heard from Rabbi Mozeson in the name of Rabbi Soloveitchik.

I also noted certain authorities from Tosafist circles who did not endorse the prohibition of Torah study for women.

For example, I quoted Rabbi Isaiah ben Elijah of Trani (Riaz, d. c. 1280) who ruled explicitly in accordance with Ben-Azzai: “Although a woman is not commanded concerning the study of Torah, if she wishes to study, she may do so.” He added that in times when the ordeal of the bitter water is practiced, “a man is required to teach his daughter Torah, so that if she drinks the bitter water… she will know that merit suspends punishment” (Piskei ha-Riaz, Sota, vol. 6, ed. Abraham Liss, Jerusalem 5737, 1:2, col. 218).

I cited also Rabbi Isaac ben Joseph of Corbeil (d. 1280), who when codifying the laws of Torah study in his Sefer Mitzvot Katan, paragraphs 105-106, mentions no prohibition on teaching women Torah. Moreover, in the Introduction to his book, he states that it is intended also for women, who should “carefully study” the positive and negative commandments binding upon them (ha-keriʾa ve-ha-dikduk bahen). Studying those commandments, he adds, is useful for women just as studying the Talmud is useful for men. It is not clear whether Rabbi Isaac is comparing the women’s “careful study” to the men’s Talmud study, or contrasting them.

The talks from that 1986 international conference were never published. The text of my own talk survived over the decades in an all-but-forgotten folder in our basement. I consulted it in writing my present “Looking Backward” reflections.

Talmud la-Talmida

When Noa entered fifth grade in September 1986 in her National Religious school in the Ramot neighborhood of Jerusalem, it was announced that, as in past years, the boys would begin Talmud study, but not the girls. We parents protested. We wanted our daughters to study Talmud together with the boys. We had to fight very hard for the privilege of having our daughters study Talmud, but in the end the principal conceded. Noa loved her Talmud classes, which included the study of passages from chapters Elu Metziʾot and Ha-Mafkid. Her teacher was Emmanuel Elalouf, an affable young scholar who had studied at Yeshivat ha-Kotel. Rabbi Elalouf lives today in Beit-El.

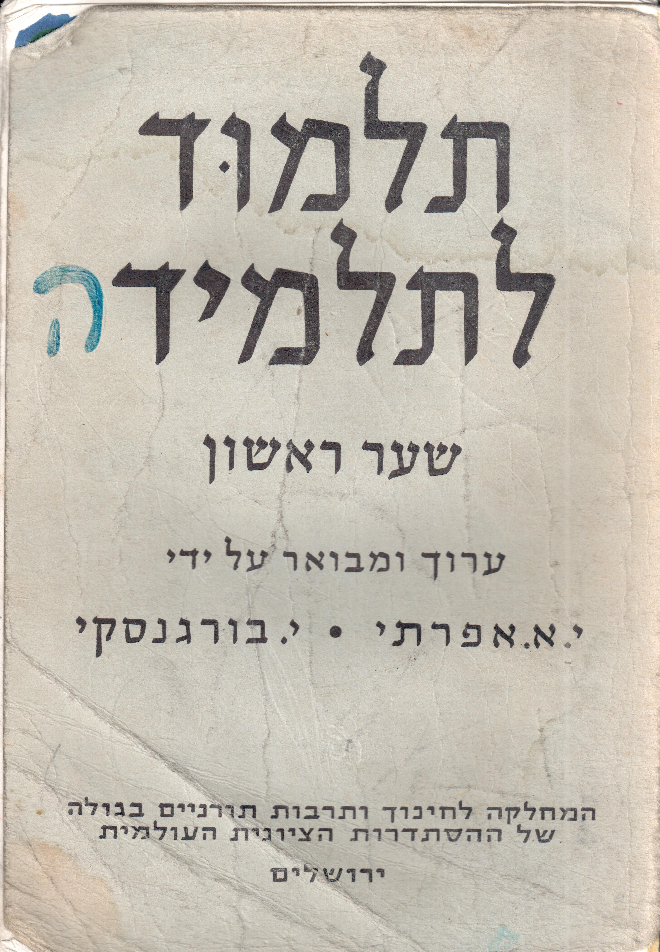

The pupils in Noa’s fifth-grade class studied Talmud from a superb series of introductory textbooks called Talmud la-Talmid (i.e., “Talmud for the Pupil”). The series was edited by Y.E. Efrati and Y. Burgansky in 1958, and was still widely used in the National Religious grade schools in the 1980s.

In their Introduction to Talmud la-Talmid, the editors explained why it is important to study Talmud. Let me quote them: “The Talmud is…the basis of Judaism… The education of a Jew has been measured according to the degree of his knowledge of the Talmud… To an individual without [the skills to study Talmud], the treasures [of Judaism] remain closed and sealed… and he is considered an ʿam ha-aretz.”

The editors’ statement is certainly true. It follows from it that if we do not teach our daughters Talmud, we condemn them to being ignoramuses in Judaism, cut off from the treasures of our people.

One day I noticed that my daughter had changed the title of her book. She had added just one letter to the title, a he. Instead of reading Talmud la-Talmid, it now read: Talmud la-Talmida (in the feminine). It was, I thought, a good slogan. Talmud la-talmida!

ʿArvei Pesaḥim: Jerusalem and New York

In June 1987, we parents informed the principal that we were pleased that the girls had studied Talmud in fifth grade, and wanted them to continue Talmud studies in the following year as well. The principal concurred that the experiment had worked extremely well, and he agreed to allow them to continue in the Talmud class in the sixth grade. We bought for Noa the Talmudic chapter that her class was to study, ʿArvei Pesaḥim, and she began to study it.

However, on the first day of classes in September 1987, the Talmud teacher announced his refusal to teach the girls, and removed them from the class. He explained to the principal that his rabbi had forbidden him to teach Talmud to girls.

That fall semester I was on sabbatical from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and taught at Yeshiva University in New York City. A few days after the girls were banished from the Talmud class in Ramot, Noa was enrolled at Manhattan Day School on New York’s Upper West Side, a school run under the guidance of Rabbi Shlomo Riskin. That afternoon Noa returned from school smiling widely, her Talmud in her hand. Her class was studying ʿArvei Pesaḥim, and she had already memorized the opening debate of the chapter. Her teacher was Rabbi Michael Fredman. Until this day she remembers vividly his inspiring classes. He lives today in Efrat.

When Noa returned to her National Religious school in Ramot in January 1988, she found that the Talmud class was restricted only to the boys. Similarly, the girls were not taught Talmud in the 7th and 8th grades. All parental protests were to no avail.

The Pelech Interview

In spring 1990, Noa was interviewed by the acceptance committee of the prestigious Pelech High School in Jerusalem. On the committee were the outgoing principal, Professor Alice Shalvi, and the incoming principal, Shira Breuer. In the course of the interview, Noa said: “One of the reasons I wish to attend Pelech is that Talmud is taught here on a high level.”

“Do you want to be a teacher of Talmud?” Professor Shalvi asked.

“No, not at all,” Noa answered. “I want to be a physicist. However, if I can’t trust a school to teach me Torah properly, how can I trust it to teach me physics properly?”

She was accepted.

What Has Changed?

Has the situation improved between the time of five-year-old Noa Eve and that of five-year-old Lia Sivan?

Noa married a Parisian and they and their three children live in les Pavillons-sous-Bois, a suburb north of Paris. Lia and her two older brothers study at the local Alliance Israélite Universelle school, and Noa teaches physics, chemistry, and computer science in the school.

Clearly, Orthodox women have many more opportunities for Talmud study today than they did when I wrote “The Obligation of Talmud on Women According to Maimonides” in 1981. Over the past 40 years, we have witnessed the establishment of many excellent institutions of higher Torah learning for women in Israel, North America, Europe, and elsewhere. This development is of consummate importance.

Nonetheless, in the great majority of National Religious schools in Israel today, girls are still wholly excluded from Talmud study. This outrageous fact reflects the conservative or reactionary tendencies of the majority of religious Jews in Israel today. The situation in France is even worse. In the Alliance Israélite Universelle school in les Pavillons-sous-Bois, the girls do not study Talmud. Noa hopes that this will change by the time Lia reaches middle school. Noa already teaches physics, chemistry, and computer science, but to ensure that none of her children grow up to be ʿamei ha-aretz, she plans to add another subject to her teaching load – Talmud.

Looking backward at “The Obligation of Talmud on Women according to Maimonides” after almost four decades, one should conclude with neither optimism nor pessimism: much progress has been made in making it possible for women in the Orthodox community to study Talmud, but the situation is still very far from satisfactory.

Warren Zev Harvey is Professor Emeritus in the Department of Jewish Thought at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, where he has taught since 1977.

“Looking Backward” is an occasional feature on TraditionOnline.org in which we ask our authors to re-explore classic essays from our pages and their ongoing contributions to religious thought.

[1] In what follows, I try to reconstruct Rabbi Soloveitchik’s halakhic position concerning Talmud and women on the basis of my conversation with Rabbi Mozeson in 1981. I thank Rabbi Raphael Groner of Yeshivat Birkat Moshe and Rabbi Professor Ephraim Kanarfogel of Yeshiva University who kindly discussed with me Rabbi Mozeson’s report back in the 1980s. Rabbi Mozeson, who passed away in Israel in 2008, wrote on the subject in his Echoes of the Song of the Nightingale (Shaare Zedek, 1991), 259-262.

[Published on January 20, 2020]