Man as an Enigma in Modern Jewish Thought

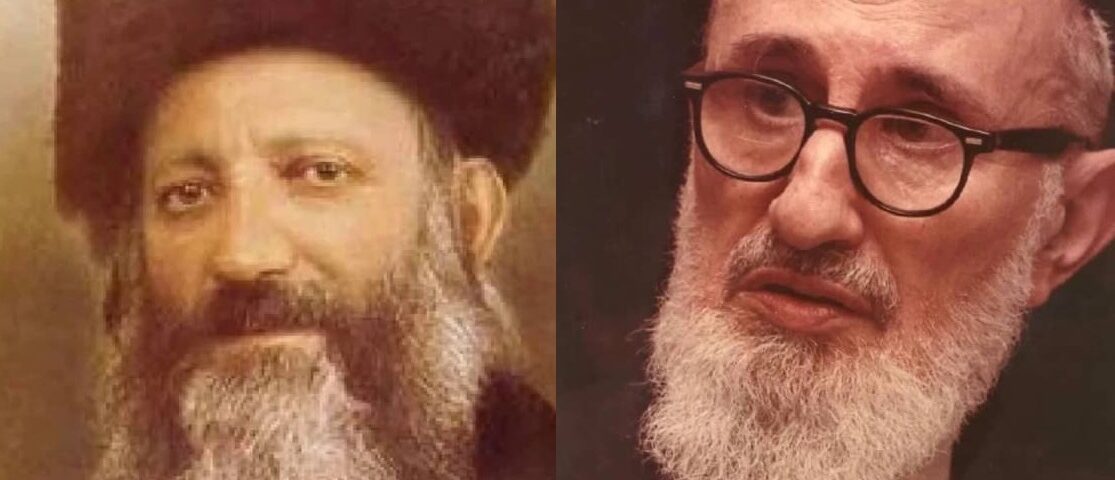

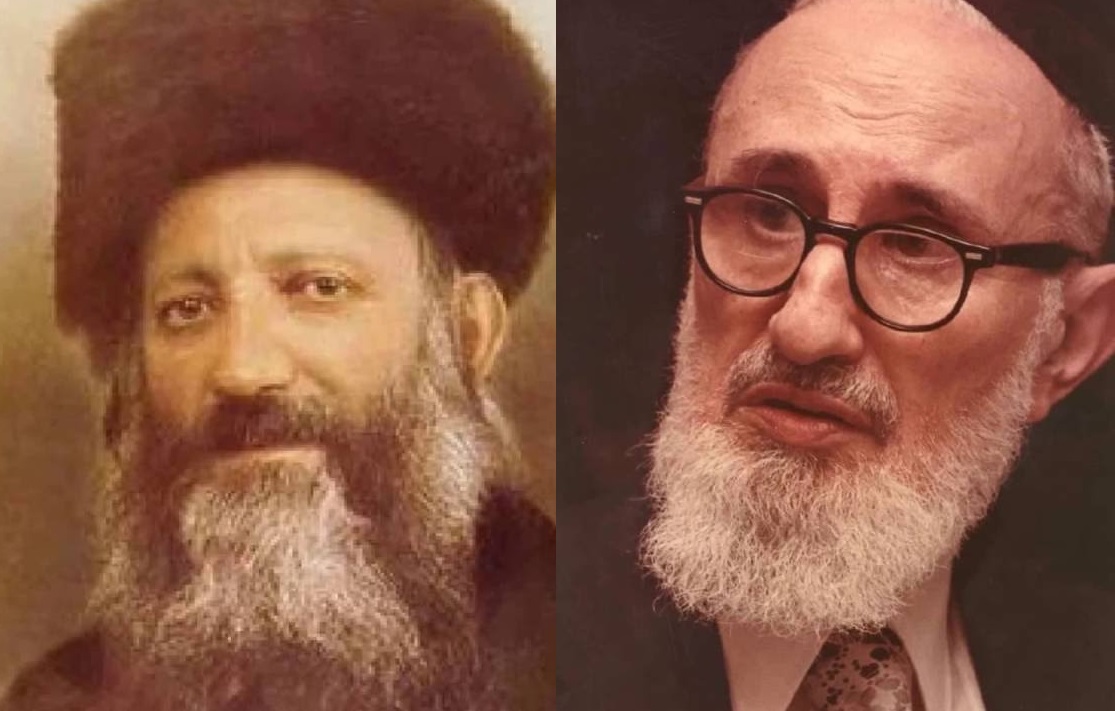

Modern society functions under the implicit assumption that God does not play dice with the universe; rather, we experience nature as rational and deterministic. We drive over bridges and fly in planes because we believe that the laws of physics will hold. When pushed to its logical conclusion, this worldview rejects the possibility of any inherently unknowable phenomena. Anything we cannot understand, any mystery, is simply a shortcoming of our current scientific capabilities. Arthur Clarke summed up this idea well when he stated that any significantly advanced science is indistinguishable from magic.1 As a contrast, two giants of Jewish thought living in this modern age, Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook and Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik, argue that there does exist an inherently unknowable phenomenon: man. The natural universe may be completely rational and deterministic, but man possesses an enigmatic nature that transcends the grasp of scientific inquiry. While R. Kook and R. Soloveitchik approach the source of man’s enigmatic nature from slightly different perspectives – R. Kook believes it results from paradoxes built into man’s identity; for R. Soloveitchik it is a product of man’s oscillation between dialectical poles – both see this enigmatic nature as a crucial indicator of religion’s continued relevance in modernity. Only religion, with its extra-rational, revelatory insights, can explain and derive meaning from the enigmatic nature of man.

Modern society functions under the implicit assumption that God does not play dice with the universe; rather, we experience nature as rational and deterministic. We drive over bridges and fly in planes because we believe that the laws of physics will hold. When pushed to its logical conclusion, this worldview rejects the possibility of any inherently unknowable phenomena. Anything we cannot understand, any mystery, is simply a shortcoming of our current scientific capabilities. Arthur Clarke summed up this idea well when he stated that any significantly advanced science is indistinguishable from magic.1 As a contrast, two giants of Jewish thought living in this modern age, Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook and Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik, argue that there does exist an inherently unknowable phenomenon: man. The natural universe may be completely rational and deterministic, but man possesses an enigmatic nature that transcends the grasp of scientific inquiry. While R. Kook and R. Soloveitchik approach the source of man’s enigmatic nature from slightly different perspectives – R. Kook believes it results from paradoxes built into man’s identity; for R. Soloveitchik it is a product of man’s oscillation between dialectical poles – both see this enigmatic nature as a crucial indicator of religion’s continued relevance in modernity. Only religion, with its extra-rational, revelatory insights, can explain and derive meaning from the enigmatic nature of man.

R. Kook identifies two paradoxes within man, the first of which appears in his explanation of the blessing of asher yatzar, which extols the miracle of the human body.2 Prompted by the blessing’s use of the root p.l.a, or wonder, R. Kook clarifies what makes man wondrous in contrast to the natural world, which is ordinary because it follows predictable laws of causal, mechanical determinism without any deviation. A ball thrown into the sky will fall. A hungry predator will instinctively search for prey. Thus, the accuracy and precision of the body’s functions alone cannot suffice to distinguish it from the rest of nature and deem it a wonder. Rather, the wonder of man unfolds from the illogical fusion of the precision of his mechanistic body with his crowning glory, the inscrutable, unpredictable gift of free will. Man functions within the space between the stimulus and his reaction, where he mayest rule over sin and choose between the good and evil in front of him. Yet, simultaneously, man’s body locks him out from its inner chambers. He may not command his heart to pump, his lungs to breathe, his blood to flow, nor his neurons to fire. These processes, occurring mechanistically without thinking or intent, lay beyond the reach of man’s free will, happening automatically as he makes his choices. Man, then, as he inhabits both these worlds, like a mixture of oil and water, is a walking paradox, an oxymoron, a wonder.

R. Kook identifies another paradox amidst his exposition of teshuva, which he defines not only as an isolated, personal act, but also as a more universal process, the lifeblood of time and the fabric of reality itself.3 All facets of reality, the individual, the community, and time, aspire towards a specific goal: the revelation of Godliness. The arc of history bends toward Godliness. In this worldview, the purpose of creation and man is to close the gap between the real and the ideal, between what is and what might be.

If history describes the movement from brokenness to wholeness, then progress depends on the existence of brokenness. Brokenness signals that history is not complete and must keep moving until it reaches stasis in the complete revelation of Godliness. A static history, one that has achieved perfection, is a completed history. In parallel, man, who stands at the center of creation, is a dynamic being, always perfecting himself and the surrounding world. If the essence of reality is the striving for wholeness and perfection, then the essence of man is also to strive for wholeness and perfection. This creates a paradoxical definition of human perfection. A perfect human is not defined by perfection, but rather specifically by the constant desire for the very perfection that he lacks.4 A perfect human being is an oxymoron. The religious man, par excellence, must hate poverty, licentiousness, oppression, falsehood, hypocrisy, and death. Yet, at the same time, the entirety of his existence, worth, and importance relies on the existence of these evils.

Similarly, much of R. Soloveitchik’s thought revolves around man’s dialectic nature, the conflicting feelings and actions built into the human experience.5 Man oscillates between two opposite poles, which are modeled by Adam in the first chapter of Genesis, termed Majestic Man, and Adam of Genesis’ second chapter, termed Redemptive Man.6 In the former, God commands Majestic Man to subdue and dominate the world around him, to build towers to the sky, subjugate the natural forces to his will, and feel a sense of majesty, confidence, and security. The very next chapter introduces us to the diametrically opposed Redemptive Man, who tills the land, expresses his existential loneliness to others, and feels a sense of humility. Each person contains both archetypes in their “DNA.” This schism is unsolvable. A man may spend his days in a professional setting, working with others in a functional manner to create something novel, and spend his evenings pouring out his heart’s desires and worries before friends and God.

R. Kook and R. Soloveitchik approach man’s enigmatic nature from different angles. R. Kook portrays man’s enigmatic nature, driven by the paradoxes that riddle his identity, by looking outward. The paradox of the human body can only be understood in contrast to the larger and predictable natural world. Similarly, the paradoxical human need for brokenness parallels reality’s dependence on brokenness. In the search for a resolution, these paradoxes take us outward beyond the bounds of our reality into the divine realm. For R. Kook, just as two contradictory verses require a third for resolution, so too the paradoxical elements of man require God to unify them. The paradoxes of the human body and the human need for brokenness attest to the footprint of a Divine creator who can perform the impossible by unifying the contradictory. As Rabbi Jonathan Sacks observed, the meaning of a system must lie beyond the system, and thus the meaning of the reality must lie beyond reality and in God.7

In contradistinction, R. Soloveitchik portrays enigma by looking inwards, by stepping into the shoes of man and describing his dialectical experiences. Through these descriptions, R. Soloveitchik expresses a grievance against modernity’s overemphasis on Majestic Man. Modernity, marked by science, emphasizes man as a being who understands the world and thereby subjugates it to his will. Yet, in the modern age, this mindset oversteps its bounds and pollutes other areas of life. Man ignores his need for emotional connection and sees others as utilitarian partners in his endeavors. Even religion, which values humility and vulnerability in the face of God, becomes a utilitarian exercise. Prayer becomes just another technology to subordinate God to man’s will, and religious rituals are reduced to services that provide man with meaning.

Yet, despite their differences, both these thinkers highlight the enigmatic nature of man to argue for the continued relevance of religion in the age of modernity. The paradoxes that R. Kook highlights serve to expand our consciousness and beget the realization that we cannot understand and thereby subjugate everything, that there is a divine harmony that can only be found beyond the limits of science and human knowledge. R. Soloveitchik finds that modern man, who abandons religion and worships at the temple of science, overly emphasizes Majestic Man and ignores Redemptive Man.8 Religion reminds man not to neglect Redemptive Man, that man cannot escape his need for existential companionship, that this dialectical tension is inescapable and must be confronted. Only religion, with its divine origins, can provide insight and guidance to man on how to deal with his enigmatic nature, whether to seek harmony in the divine or to embrace both dialectical poles, to continue on where human understanding ends.

Natan Oliff works as a software development engineer at Amazon.

- Arthur C. Clarke, “Hazards of Prophecy: The Failure of Imagination” in Profiles of the Future (Pan Books, 1973), 36.

- Abraham Isaac Kook, Olat Reiyah, vol. 1, p. 4.

- Abraham Isaac Kook, Orot Ha-Teshuva, 4:1.

- Ibid. 5:6.

- Joseph B. Soloveitchik, “Majesty and Humility,” TRADITION 17:2 (1978), 25-37.

- Joseph B. Soloveitchik, “The Lonely Man of Faith,” TRADITION 7:2 (1965).

- Jonathan Sacks, The Great Partnership: Science, Religion, and the Search for Meaning (Schocken, 2012), 9.

- “Contemporary Adam the first, extremely successful in his cosmic-majestic enterprise, refuses to pay earnest heed to the duality in man and tries to deny the undeniable, that another Adam exists besides or, rather, in him. By rejecting Adam the second, contemporary man, eo ipso, dismisses the covenantal faith community as something superfluous and obsolete” (“The Lonely Man of Faith,” 106).