Mourning Through a Glass Pane

In this week’s parasha, The Torah tells us that when Jacob is first reunited with Joseph after twenty-two years of believing his beloved son was dead, Joseph “appeared to him, and he fell on his neck, and he wept on his neck for a long time” (Gen. 46:29). Jacob’s passive behavior during the encounter with his long lost son is puzzling – only Joseph is falling and weeping; what was Jacob doing? Rashi, citing the Midrash Aggada, suggests that the patriarch was occupied with the recitation of Shema.

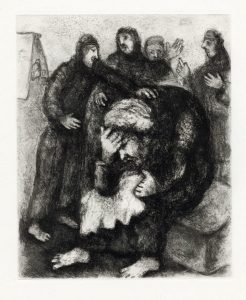

Chagall, “Jacob Weeps for Joseph”

But another explanation is possible. The Torah doesn’t state that Jacob wept, because it would be absolutely tautological to do so. We’re not told that the father is crying now, because he’s been crying for over two decades! “And all his sons and all his daughters arose to console him, but he refused to be consoled, for he said, ‘Because I will descend on account of my son as a mourner to the grave,’ and his father wept for him” (Gen. 37:35). When a child dies, part of the parent never stops crying, even as other parts may heal.

Parents who suffer the loss of a child are initiated into the unenviable fellowship of the shakhul, the Hebrew term reserved for the special category of bereaved parents. (See, for example, Genesis 27:45, 42:36, 43:14.)

While comforting mourners is embedded in our Jewish values, confronting the grief of the shakhul poses a host of complications to an already emotionally charged moment. Among the challenges is the unfathomable distance between the mourner and the comforter who can only glimpse the bereaved from what is surely another world

In thinking back to the death of my premature daughter I often recall the words of the Bosnian-American novelist Aleksandar Hemon, who described the days of his own daughter’s final illness this way:

One early morning, driving to the hospital, I saw a number of able-bodied, energetic runners progressing along toward the sunny lakefront, and I had a strong physical sensation of being in an aquarium: I could see out, the people could see me (if they chose to pay attention), but we were living and breathing in entirely different environments.

Looking through the thin glass pane of my own “aquarium” while numbly sitting in shul on the Friday night following her death, I wanted to shout out to those on the other side: “I had a daughter, her name was Neshama Chaya, she lived and died this week, she spent her whole short life in the NICU, and none of you will ever know her!”

Kind people tried to tell us from their side of the glass, “You’re young, you can have other children,” and this, thank God, proved to be true, yet entirely missed half the point. When parents lose a child, part of the grief is really for themselves – for however many months they anticipated the arrival, or for however many years they parented and watched them grow, so much of the parents’ life becomes enwrapped in the anxiety and expectation connected with the child – emotionally, mentally, spiritually and even physically. With their death, the parents mourn not only the child, but their own lost expectations, hopes, and dreams as well. The idea that one can have other children is indeed a comfort. And yet, that child is gone from this world forever, leaving an indelible mark, and emotional scar, on the mother and father.

I recalled these ideas, which were first expressed in the introduction to To Mourn a Child: Jewish Responses to Neonatal and Childhood Death (OU Press, 2013), co-edited with Joel Wolowelsky, while watching the moving conversation between Chief Rabbi Ephraim Mirvis and Archbishop Justin Welby. You see, both men have buried children. Their conversation, and commitment to more directly addressing this category of loss from within their individual faith traditions, is the very best type of “interfaith” dialogue. It is spiritually profitable to believers of all faiths (and those with no faith or lost faith) because it shows the two men interacting in an authentic, personal, human manner, leading to insights that both comfort and enlighten us all.

R. Jeffrey Saks is the editor of TRADITION.