New/Old American-Jewish Realities

When the Strong Do What They Can, What Must the Jew Suffer?

For much of the modern era, Jewish life rested, quietly but decisively, on an implicit promise. Power would be constrained by law. Markets would be disciplined by norms. States would bind themselves to rules they did not invent solely for their own advantage. The weak would be protected not by benevolence but by structure. Jews, long practiced in the arts of minority survival, understood and benefited from this promise.

That promise is fraying. We are entering a world in which power no longer feels obligated to justify itself; where rules are treated as optional by those strong enough to ignore them; where cruelty need not even disguise itself as necessity. Antisemitism in such a world is not an aberration. Judaism has lived through this world before. But modern Jewish institutions were not built for it.

When the rules-based international order collapses, we do not return to neutrality. We return to hierarchy. We return to raw power, transactional loyalty, and moral improvisation. In Jewish terms, this geopolitical shift becomes a civilizational test, because Judaism, at its core, defies unaccountable power.

It’s not just the Pharaohs of history. The Creator of the world does not rule by whim. Even divine authority binds itself to law. The God of Israel is bound by His own covenant, accepts argument, and allows human beings to appeal to justice against power. Abraham challenges divine judgment at Sodom. The prophets indict kings not for malfeasance but for strength exercised without restraint. Judaism’s deepest instinct is that power must answer to something higher than itself.

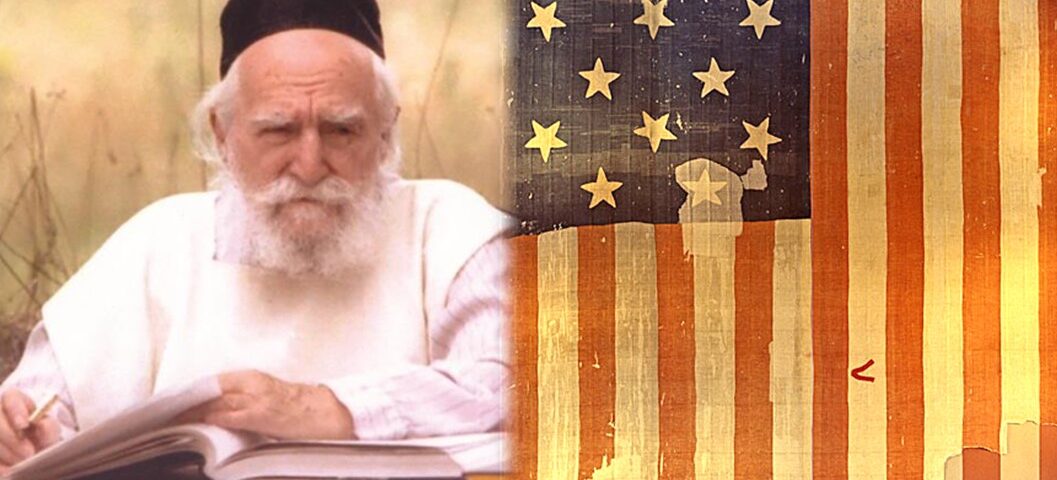

It is here that R. Moshe Feinstein’s famous description of the United States as malkhut shel hesed (Iggerot Moshe, H.M., vol. 2, #29) deserves careful reappraisal. R. Feinstein was not naïve about America. He did not claim that the United States was righteous, innocent, or immune to corruption. What he recognized, brilliantly and gratefully, was something more precise: that America, uniquely in Jewish history, embedded kindness into its legal and civic structures. Hesed was not dependent on the goodwill of a ruler or the mood of a mob. It was routinized, bureaucratized, and protected by law. For Jews, this was unprecedented: not perfection, but reliability.

It is here that R. Moshe Feinstein’s famous description of the United States as malkhut shel hesed (Iggerot Moshe, H.M., vol. 2, #29) deserves careful reappraisal. R. Feinstein was not naïve about America. He did not claim that the United States was righteous, innocent, or immune to corruption. What he recognized, brilliantly and gratefully, was something more precise: that America, uniquely in Jewish history, embedded kindness into its legal and civic structures. Hesed was not dependent on the goodwill of a ruler or the mood of a mob. It was routinized, bureaucratized, and protected by law. For Jews, this was unprecedented: not perfection, but reliability.

America allowed Jews to assume that rules would hold even when sympathies failed; that contracts would be enforced even when Jews were disliked; that rights would persist even when kindness waned. R. Feinstein understood that this structural hesed created conditions in which Torah could flourish openly, institutions could expand confidently, and Jewish vulnerability could recede into the background of consciousness.

But a “nation of kindness” was never a theological category. It was a historical one. Judaism never taught that such a state would forever endure. As the rules-based order weakens, the hesed R. Feinstein described cannot be assumed or taken for granted. Law becomes selective. Enforcement becomes political. Sympathy becomes conditional. In such a world, antisemitism does not merely return; it finds justification. Jews are once again portrayed as “beneficiaries” of corrupt systems, symbols of constraint in a culture that resents limits.

The response cannot be nostalgia for an America that was. Nor can it be naïve faith that institutions will save us if we are patient and polite. Judaism has never trusted power to restrain itself voluntarily. It has always assumed the opposite. What Judaism must recover now is not relevance but seriousness. We need serious Jews.

Jewish history outside America offers abundant instruction. In Babylonia, Jews lived for centuries under imperial rule with little political power, yet built durable systems of self-governance. The Geonim exercised authority not because the state empowered them, but because Jews accepted obligation as binding even when unenforced. In medieval Europe, Jews survived amid hostility and expulsion by developing fiercely independent legal cultures, takkanot, communal courts, mutual aid societies that regulated behavior when external justice was unreliable or hostile. Powerlessness sharpened discipline rather than dissolving it. Judaism did not survive these worlds by demanding kindness. It survived by assuming its absence.

Modern Jewish life, shaped so profoundly by America, internalized a different grammar: rights, recognition, inclusion, choice. These were not mistakes. They were appropriate to a world in which law mediated power. But in a world where rights are unenforced and norms unenforceable, Judaism’s older language becomes indispensable again: duty, discipline, restraint, fear of Heaven. Halakha was never designed for comfort; it was designed for continuity under pressure.

Jewish institutions must also prepare for moral loneliness. The prophets were not popular. Neither were the rabbis of the Mishna, medieval Europe, or the early modern period. Jewish leadership has often meant standing without allies, defending norms no one else finds convenient.

The fantasy that antisemitism can be eliminated through better messaging misunderstands its function. Antisemitism thrives when societies abandon self-limitation. Jews cannot cure that illness. We can only refuse to internalize it. This requires leaders willing to disappoint donors, alienate fashionable opinion, and speak in moral categories that do not trend well. The test of leadership in a post-rules world is not coalition-building alone, but endurance.

A world without rules does not become neutral; it becomes predatory. Judaism has always known this. That is why the Torah binds the strong with obligations to the weak: the landowner to the poor, the creditor to the debtor, the ruler to the stranger. Jewish ethics are not a luxury of stability; they are a discipline for instability. Even when Jews lacked power, they did not abandon this ethic. Even when surrounded by cruelty, they insisted on limits Those limits emerged from internal Jewish intellectual and spiritual life, through studying and living halakha.

In this moment, Judaism must reclaim its long view of history. The rules-based order felt permanent because it coincided with a long period of Jewish flourishing. That coincidence was a gift, not a covenant. R. Feinstein gave thanks for America’s hesed without confusing it for redemption.

Jewish time is measured differently. Empires rise and fall. Moral languages exhaust themselves. Covenants endure. The end of a rules-based world is not the end of Jewish purpose. It is a return to familiar terrain. Judaism does not require universal kindness to survive, but it does require internal coherence, moral courage, and fidelity to law when law is unfashionable.

If America becomes less of a malkhut shel hesed, Judaism must remember how to live without assuming charitable goodwill from others—while never surrendering its obligation to practice it itself. The question is not whether Judaism can adapt to a post-rules world. It was born for one. The question is whether we remember.

Chaim Strauchler, an associate editor of TRADITION, is rabbi of Cong. Rinat Yisrael in Teaneck.