Open, Closed, Open

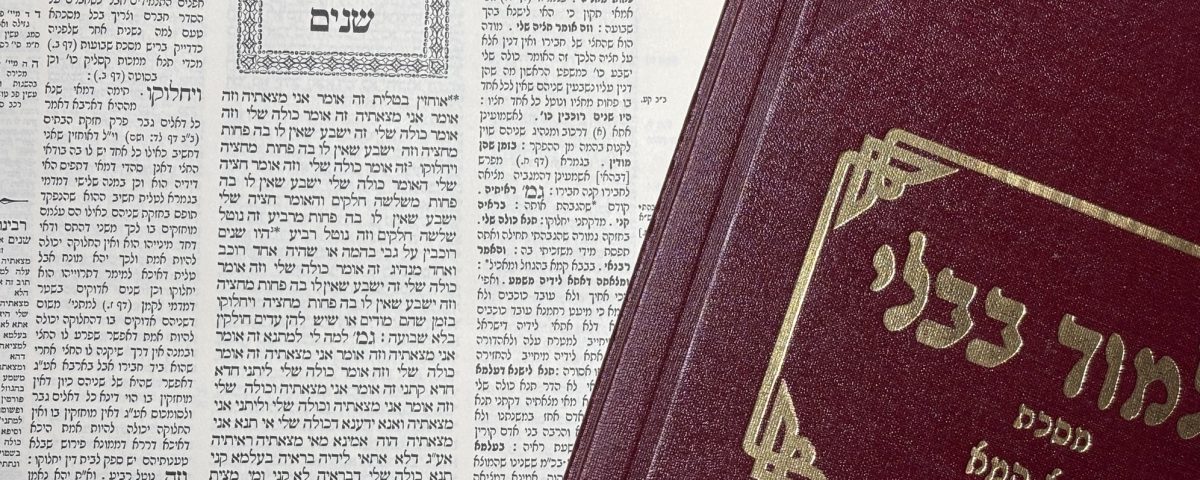

There is a story that is often told in the yeshiva world, about a group of young men who were sitting in the beit midrash in Radin, learning diligently deep into the night. They were so absorbed in the Gemara, and engaged with each other in the sounds of study and learning, that they ignored the lateness of the hour. The Rosh Yeshiva, the sainted Hafetz Hayyim, whose modest apartment was next to the beit midrash, heard the sounds of learning and saw the lights burning beyond the usual hour. In the middle of the night he entered the beit midrash together with the yeshiva’s director and ordered the students to stop their learning and go to bed immediately in order to preserve their health. The students refused the order and continued to study with increased enthusiasm. In response, the Hafetz Hayyim climbed onto the benches and extinguished the beit midrash’s oil lamps one by one.

There is a story that is often told in the yeshiva world, about a group of young men who were sitting in the beit midrash in Radin, learning diligently deep into the night. They were so absorbed in the Gemara, and engaged with each other in the sounds of study and learning, that they ignored the lateness of the hour. The Rosh Yeshiva, the sainted Hafetz Hayyim, whose modest apartment was next to the beit midrash, heard the sounds of learning and saw the lights burning beyond the usual hour. In the middle of the night he entered the beit midrash together with the yeshiva’s director and ordered the students to stop their learning and go to bed immediately in order to preserve their health. The students refused the order and continued to study with increased enthusiasm. In response, the Hafetz Hayyim climbed onto the benches and extinguished the beit midrash’s oil lamps one by one.

At least that’s how I heard the story. It’s how my father told it to me many years ago when he drove me to Yeshivat Yeruham on Rosh Hodesh Elul, and this is how my rabbis in the yeshiva also told it. The message of the story was simple: If the HafetzHayyim himself bothered to turn out the lights for his students, you too can make sure to get a reasonable amount of sleep, eat proper meals, and even make an occasional phone call to your parents. You are no more righteous than the Hafetz Hayyim.

But recently it became clear to me that this story has a little-known sequel. The diary of one of those students, Rabbi Yitzhak Ben-Menachem, tells what happened after the Hafetz Hayyim called for lights out: “We remained glued to our seats, captivated by the phenomenon we had witnessed. After we recovered, we got up on the benches, and relit the lamps!” A few minutes later, the yeshiva’s director re-entered the beit midrash, alone this time. He looked at the rebellious students, then “hastily went to his usual place in the corner of the Eastern Wall next to the Holy Ark, and also took out a Gemara and immersed himself in learning with supreme enthusiasm.”

This Rosh Hodesh Elul, I myself am sending a son off to a yeshiva (a high school, admittedly, but still…). I would like to tell him and his friends, and the students at yeshivot everywhere, both parts of the story. We want to tell you two different, opposing messages. We want to turn off the lights at the end of the night, but secretly in our hearts we are waiting for you to turn them back on despite our instructions. In fact, even if we don’t know how to say it out loud, we turn off the lights precisely to let you know that you should relight them, as we did when we were your age.

We would like the Torah to be sweet as “stolen water” (Proverbs 9:17). Because it has always been thus, from the moment Moses ascended to heaven to claim it, despite the anger and opposition of the ministering angels who cry out, “What place does a mortal man have among us?” Moses did not accept the Torah out of a sense of obligation, nor even out of a sense of it being given to him as a gift. He “snatched” it away because he was incapable of anything else. Some inexplicable spark lit him—like those after-hours lamps in the Radin beit midrash. All is fair in love of Torah.

This is even more true after the past two years. Our rabbis used to say in the name of Rabbi Zvi Yehuda Kook that he who does not know when to close the Gemara had better not open it in the first place. But two decades ago, between volunteering in the community and demonstrating against the Gaza disengagement plan, we students used to remind each other that he who does not know when to open the Gemara again had better not close it. When we look around at the Hesderniks who fill the fighting units, our hearts burst with love and gratitude for a generation that knows when to close the Gemara at need. And in contrast, we are alarmed by the opposing portrait of a society for whom the Torah has become a deadly potion disconnecting its members from life. It is precisely our own religious community’s moral clarity which encourages us not to abandon our desires—Turn the Torah into your rebellion, into a compass to steer you straight, pointing you for when you must exit the beit midrash, and guiding you back inside once again. Let it open your heart and take you on a journey to destinations unknown. After these two years, we are no longer afraid of the second part of the story. We know that you can embark on this journey to where it must take you and return from there to where you began. In T.S. Eliot’s words: “We shall not cease from exploration / And the end of all our exploring / Will be to arrive where we started / And know the place for the first time.”

Rabbi Avraham Stav teaches at Kollel Shaarei Zion in Yad HaRav Nissim, Jerusalem, when he is not serving in an artillery unit.