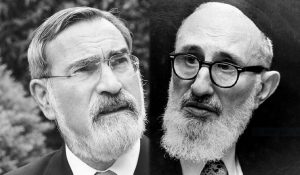

R. Sacks and the Quest for Authentic Jewish Thought

Rabbi Jonathan Sacks zt”l, to my mind the most important Orthodox Jewish theologian of the twenty first century, was in constant dialogue with Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik, the most important Orthodox Jewish theologian of the twentieth century. R. Sacks’ first published essay on Jewish theology, entitled “Alienation and Faith,” published in TRADITION in 1973, is a response and a critique of R. Soloveitchik’s monumental essay, “The Lonely Man of Faith” (which had appeared in TRADITION just eight years earlier). It is remarkable to note that at the age of twenty-five, R. Sacks had the self-confidence to challenge in print the thesis of the unchallenged intellectual leader of Modern Orthodoxy.

Rabbi Jonathan Sacks zt”l, to my mind the most important Orthodox Jewish theologian of the twenty first century, was in constant dialogue with Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik, the most important Orthodox Jewish theologian of the twentieth century. R. Sacks’ first published essay on Jewish theology, entitled “Alienation and Faith,” published in TRADITION in 1973, is a response and a critique of R. Soloveitchik’s monumental essay, “The Lonely Man of Faith” (which had appeared in TRADITION just eight years earlier). It is remarkable to note that at the age of twenty-five, R. Sacks had the self-confidence to challenge in print the thesis of the unchallenged intellectual leader of Modern Orthodoxy.

The Rav, based on a close reading of the first two chapter of Genesis, argues that there are two typologies of Man. Majestic Man is dignified in his domination of the natural world through the use of his intellect and technological achievements, whereas Covenantal (or, Redemptive) Man is loyal and submissive to his Creator. Man is doomed to a lonely existence because each of these typologies exists in conflict within him. In R. Sacks’ words, the Rav portrayed the “alienation of the man of faith… not a consequence of a sense of meaninglessness, but rather the opposition of two sharply sensed and incompatible meanings. His self is not so much distanced from the world as divided within itself” (“Alienation and Faith,” 139).

R. Sacks argues against this interpretation of the biblical narrative, and, based on Rashi and Cassuto, he presents a different picture:

There is a natural reading of Genesis 1 and 2…according to which the two accounts of creation do not give rise to a dualistic typology of the man of faith. Instead, they describe a state in which an apparent tension is brought within a single harmonious mode of activity whose consequence is at the polar opposite from alienation and internal discord… Of all the phenomenon, spiritual and social, that characterize contemporary existence, centrality of significance belongs to alienation. (“Alienation and Faith,” 149).

Three things are readily apparent from this brief essay: R. Sacks’ insistence that Jewish theology is relevant for all of mankind, the biblical source of his thought, and his intellectual creativity and independence. This pattern continues in most of R. Sacks’ future work, which can be read as an ongoing theological interpretation of the Bible for the post-modern man.

In his numerous writings over the course of decades, R. Sacks consistently looked to the biblical text as the source of his modern theology. His theological interpretations go beyond the traditional use of the Torah as a starting point for homiletical insights (commonly referred to as derash). Instead, they are meant to capture, using modern literary methodologies, what he feels is the simple (or peshat) meaning of the text. These original and sometimes provocative readings are the basis of his grand project to develop a modern Jewish theology for a generation skeptical of authority in general and of religion in particular.

Among R. Sacks’s most important ideas, fully developed in his book The Dignity of Difference, is the relationship between tribalism and universalism in Jewish thought. He asserts that Judaism preaches the progression from the universal to the particular. The Torah begins with God creating a covenant with all of humanity and then singles out some people (the Jews) as different – not because of any notion of moral superiority, but “in order to teach humanity the dignity of difference.” Biblical monotheism is not the idea that there is one God and therefore one truth, one faith, and one way of life. It is just the opposite: it is the idea that unity creates diversity. This idea of the dignity of the other is perhaps the most important lesson that R. Sacks can teach us in in our tragically divided small Jewish world and larger global community.

Another model of how to create a Jewish theology has been advocated by none other than R. Sacks himself. In discussing the issues of poverty, work, and income redistribution from a Jewish perspective, R. Sacks begins with a methodological note:

Judaism and Christianity have a common background in the Bible, or what Christianity would call the Old Testament. From there on the paths diverge. One route led on into the New Testament and the Church Fathers. The other proceeded through the debates of the rabbis, ultimately to be collected into a vast literature of law, ethics, homily and legend of which the most influential works are the Mishna, codified in the early third century, and the Babylon and Jerusalem Talmuds, compiled several centuries later. The first point, therefore, is what I shall be describing is an alternative interpretative history that can be mapped out for the Bible. The second point: The Talmudic literature is not so much a book or collection of books, as the edited record of centuries of sustained argument over every issue which touched the life of the Jew. Argument is of its essence and decisions were reached only when absolutely necessary to establish a community of practice… How did one translate values into practical policies – that is, into law – in a world of limited resources and conflicting claims? This is where rabbinic thought has its cutting edge… These attitudes found specific expression in Jewish law (Tradition in an Untraditional Age, 183-185).

Here, R. Sacks is making the important point that from a traditional Jewish interpretative perspective, the Bible must be read through the eyes of the ancient rabbis and that Jewish law is the most authentic representation of Jewish values.

In the course of his essay, R. Sacks develops a Jewish ethics of poverty grounded in Jewish law. As opposed to the view of some other religions, Judaism considers poverty an unmitigated evil, not a blessed state. According to rabbinic law, as codified by Rambam, the highest level of charity is to provide a poor person with a job, enabling him to forego future charity (Hilkhot Matnot Aniyim 9:7). Work is an important Jewish value, as demonstrated by the rabbinic obligation to teach one’s child a trade, but biblical and rabbinic laws have built-in protections for the workers, such as the right to terminate a contract and the obligation to get paid immediately for a day’s work.

This methodological formulation is reminiscent of R. Soloveitchik’s well-known concluding contention of The Halakhic Mind: “Out of the sources of Halakhah, a new world view awaits formulation.”

In fact, it was precisely this message which was delivered to R. Sacks from none other than R. Soloveitchik himself. In an evocative essay, R. Sacks writes of his pilgrimage to the United Sates when he was a young man of nineteen to meet the theological giants of American Jewry. Everywhere he went, people told him that the one person he had to meet was R. Soloveitchik. Finally, R. Sacks tracked the Rav down before his Talmud shiur at Yeshiva University, and he was told to return the next day:

Next morning I was there, and we sat together on a bench in the corridor. Instantly the austerity was gone. In the unique kinship that is lernen, he put his hand on my shoulder and started to sway backwards and forwards expounding his philosophical thesis as if it were a difficult Tosafot. His question was fundamental: What is authentic, autonomous – what is Jewish – about Jewish Philosophy? Judaism, he maintained, had one unique heritage from which every authentic expression must flow and in reference to which every proposition must be validated: the Halakhah. A philosophy not rooted in the Halakhah would fail to capture what it sought to describe… A philosophy of the individual, his freedom and grandeur, must take as its starting point some concrete halakhic application… Halakhah was the visible surface of a philosophy; the only philosophy that could lay legitimate claim to being Jewish. That still seems in retrospect the best summary of his work (Tradition in an Untraditional Age, 269-270).

R. Sacks used this methodology, taught to him directly by the Rav, in developing his ethic of work. The Jewish view on the value of work along with built-in protection of laborers, is traced back directly to the halakhic formulations of the Talmud and the Rambam. This halakhic ethic has much relevance in developing a public policy which rewards industriousness and innovation but also has built in protection for vulnerable workers.

R. Sacks paints a beautiful portrait of the elderly giant passing on his profound wisdom to an eager, young student who would evolve into the foremost expositor of our masora for our People and for the nations of the world. R. Sacks wrote that in his visit to American he sought out people who would help him cling to something beyond himself. For a generation of Jews seeking wisdom and values in a turbulent world, now bereft of our teacher, R. Sacks was the spiritual guide we sought out and clung to.

Alan Jotkowitz is Professor of Medicine, Director of the Medical School for International Health, and the Director of the Jakobovits Center for Jewish Medical Ethics, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. Read his essay, “Universalism and Particularism in the Jewish Tradition: The Radical Theology of Rabbi Jonathan Sacks,” TRADITION 44:3 (Fall 2011).

[Published November 15, 2020]