Rabbi Lamm and Public Religious Expression

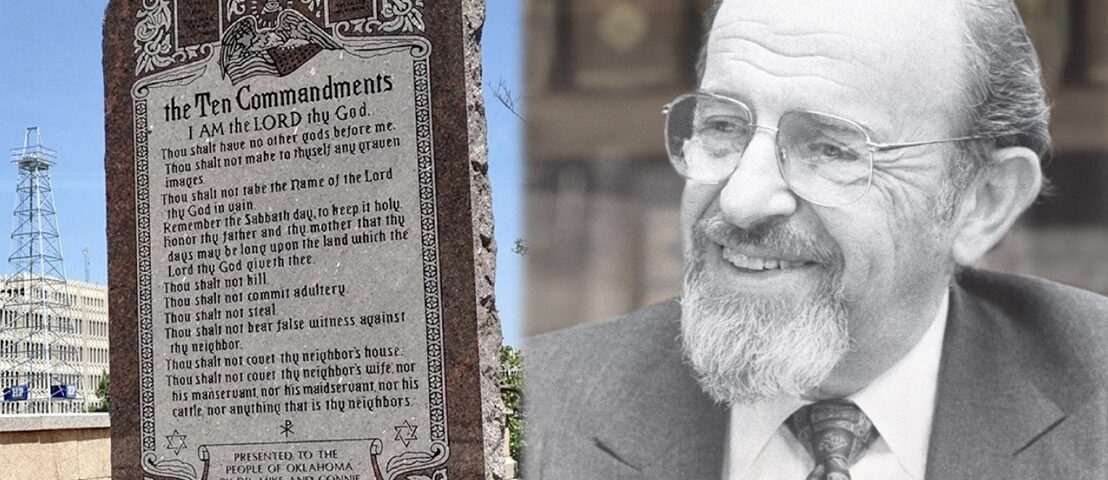

Religion in the classroom is back in the news cycle. This month, Louisiana Governor Jeff Landry signed into law a bill that will require the state’s public schools to all display the Ten Commandments in each classroom. In Oklahoma, State Superintendent of Public Instruction Ryan Walters announced a new policy that “every teacher, every classroom in the state will have a Bible in the classroom and will be teaching from the Bible in the classroom.” And this new trend is by no means an accident. As I recently explained, the Supreme Court has adopted a new method for interpreting the First Amendment’s church-state principles. Gone is the expansive, and oft criticized, Lemon test, which demanded broad separation between church and state. Instead, the Court has now signaled that the First Amendment ought to be interpreted with an eye toward the Founding Father’s original understanding of disestablishment. Such an approach opens the door to potentially greater church-state interaction than previously sanctioned by the Supreme Court.

Religion in the classroom is back in the news cycle. This month, Louisiana Governor Jeff Landry signed into law a bill that will require the state’s public schools to all display the Ten Commandments in each classroom. In Oklahoma, State Superintendent of Public Instruction Ryan Walters announced a new policy that “every teacher, every classroom in the state will have a Bible in the classroom and will be teaching from the Bible in the classroom.” And this new trend is by no means an accident. As I recently explained, the Supreme Court has adopted a new method for interpreting the First Amendment’s church-state principles. Gone is the expansive, and oft criticized, Lemon test, which demanded broad separation between church and state. Instead, the Court has now signaled that the First Amendment ought to be interpreted with an eye toward the Founding Father’s original understanding of disestablishment. Such an approach opens the door to potentially greater church-state interaction than previously sanctioned by the Supreme Court.

This new approach means that, in many ways, what’s old will become new. In the coming years, we will likely see states test the new legal regime by bringing back programs and policies that mirror legislation previously rejected by the Court. Louisiana’s new Ten Commandments law is emblematic of this dynamic; in 1980, the Supreme Court struck down a similar Kentucky law.

Like members of many faith communities, Orthodox Jews will presumably need to develop a response to these new attempts to bring religion into the public-school classroom. But that may be easier said than done. In the mid-20th century, Orthodox institutions typically partnered with other denominations when it came to introducing religion into the public-school classroom. For example, the Rabbinical Council of American and the Orthodox Union joined other Jewish institutions in filing amicus briefs before the Supreme Court in a range of prayer-in-public-school cases, including McCollum v. Board of Education (1948), Engel v. Vitale (1962), and Abington School District v. Schempp (1963).

But as the century wore on, and Orthodoxy built out its own independent advocacy institutions, not only did such joint Supreme Court briefs in religion-in-public school cases became far more infrequent, but—more often than not—Orthodox institutions simply didn’t file. And when they did, it was less about the particular stakes of religion in public schools, and more about the big picture constitutional issues. Consider, for example, the 1992 case Lee v. Weisman, where the Supreme Court considered a constitutional challenge to a rabbi’s prayer at a public-school graduation. The National Jewish Commission on Law and Public Affairs (COLPA), led by Nathan Lewin and Dennis Rapps, filed an amicus brief on behalf of the institutions of American Orthodoxy (including the RCA, OU, Agudath Israel, among others), which noted that while other filing organizations were “concerned with whether a public high school graduation program may include an address or prayer in which the deity is invoked,” “[t]hat precise constitutional issue is, in and of itself, not of sufficient significance to the Orthodox Jewish community to warrant the filing of this amicus brief.” Instead, COLPA focused its attention on criticizing the “vague and overbroad” Lemon test, which “incentiv[ized] . . . the initiation of meritless litigation and cast a heavy and unjustified burden on religious minorities and on lower courts.”

So, what other sources might American Orthodoxy mine as it develops an approach to religion in public schools? Two letters of the Lubavitcher Rebbe, from 1962 and 1964, supporting non-denominational prayer in public school represent some of the most well-known interventions in this debate—and rightfully so.

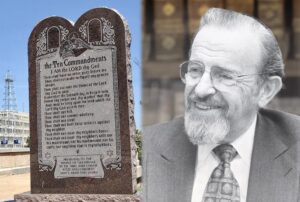

Less known is a sermon from Rabbi Norman Lamm, delivered on June 19, 1976, which provided some of his most extensive comments on what he saw as the appropriate role of religion in American society. Indeed, as I’ve explored previously in the pages of TRADITION, Rabbi Lamm often delivered sermons that addressed issues of church and state, most frequently issues of government funding for Jewish day schools.

But in 1976, Rabbi Lamm provided some broader commentary—touching upon the question of religion in public schools—in the context of what he perceived as resistance to then-Governor Jimmy Carter’s presidential candidacy. In that sermon, titled “Can We Afford a Praying Man as President?,” he argued that the Jewish community’s reluctance flowed from an “uneasiness . . . at the religious expressions of Governor Carter.”

As typical, Rabbi Lamm pulled no punches. “I suspect it lies in a dogmatic, doctrinaire secularism that is the dominant attitude in the Jewish community, and that cringes at the prospect that one who is, or seems, deeply religious will become president of this country, even if he is firmly committed to pluralism.” Thus, he argued, “It is too much for the devotees of the cult of the secular to abide the symbolism of the highest office in the land being occupied not only by a president who prays, but by a praying president.” Rabbi Lamm believed such an approach was deeply misguided. Referencing the Watergate scandal, Rabbi Lamm contended: “Something has got to be done to restore the integrity of the office of the presidency. The presidency, as we have heard time and again, is the most powerful office on earth. It cannot hurt to entrust the vast powers of this heady office to someone who knows that he is not God.”

And here, Rabbi Lamm laid out—albeit briefly—his vision for separation of church and state in America, which began with the Founding Fathers: “The fact that they did not want an established church, does not mean that they in any way discouraged religious expression.” On that note, he declared, “I am for the separation of church and state. I am not for the separation of religion and American citizens.” Pushing back, as he often did, on the Jewish community all-too enthusiastic embrace of separationism, he noted: “For too long, the Jewish community’s official attitude was almost obsessively focused on the so-called ‘wall of separation’ between church and state. This ‘wall’ has become the secular version of the Kotel Ma’aravi, the Western Wall, so cherished by religious Jews.”

And on that basis, he provided the following programmatic statements:

So let me say: even against Governor Carter, I am for more religious expression in the public life of this country, even in the public schools. I am not for denominational prayers. I am certainly not for coerced prayers in public schools. But I would like to see the kind of situation (and here is not the place for going into details on this subject) which would foster more respect for religious life and more religious expression in American life.

No doubt, the parenthetical aside is tantalizing. But lack of details aside, in this brief paragraph, Rabbi Lamm outlined a constitutional approach that may very well track the Supreme Court’s new approach to the First Amendment. Prayers in public school cannot be so sectarian so as to prefer one religious denomination over another. And no child in public school should ever be put in a position where he or she feels coerced to participate in prayer. At the same time, the idea—embedded so centrally in the now discarded Lemon test—that the intentional introduction of religion into the classroom is constitutionally verboten may be a step too far. Put differently, Rabbi Lamm envisioned an America that embraced religion without embracing a religion—and that made room for religion without imposing religion.

No doubt, this sort of constitutional balancing act is hard to pull off. Indeed, it is precisely because the risks are high that Americans may be far better served by a regime that keeps church and state in their respective corners. But one can also see why such an approach may be appealing to American Orthodoxy. It is a vision that sees religion as essential to society and even politics, while still aspiring to protect every faith community—large and small—from the devastating consequences of government-sanctioned religious coercion and denominational preferences.

Will that become the approach of American Orthodoxy in our new legal environment? Time will tell. As Rabbi Lamm might say, the risks are high, but so are the rewards.

Michael A. Helfand is the Brenden Mann Foundation Chair in Law and Religion at Pepperdine Caruso School of Law, Florence Rogatz Visiting Professor at Yale Law School, Senior Legal Advisor to the Teach Coalition and Senior Fellow at the Shalom Hartman Institute. Read his “A Vision for Church-State Advocacy: R. Lamm’s Challenge to Separationist Faith” from TRADITION’s Rabbi Norman Lamm Memorial Volume.

1 Comment

An excerpt from my book manuscript Jews have Green Hair:

School Prayer

Did the Founding Fathers mandate by “Separation of Church and State” that Atheism should be the State Religion? I think not. Would a complete ban on prayer in public schools violate the Constitution’s requirement for Freedom of Speech? I think so. But to coerce even one student to only sit silently while others pray is clearly a violation of the “Separation.” May I suggest a possible method to satisfy all requirements?

Case 1. A majority of students in a particular classroom wish to open the school day with a definitely Christian prayer.

1a. A Christian prayer is sung, recited, or read by the majority.

1b. The several Jewish students or one representing them then sings, recites, or reads a Jewish prayer, facing his/her classmates. The teacher may suggest a Psalm if the student doesn’t have one prayer particularly in mind. And if the Christian classmates join in, OK.

1c. Any member of another minority religion, Islam, Buddhism, Hinduism, etc. can have the same privilege as the Jewish students.

1d. Any Secular Humanist or Atheist student may read any short literary work that illustrates his/her philosophy, such as works from Shakespeare, Lincoln, Dwight Eisenhower, Harry Truman, Washington (George or Booker T.), Roosevelt (Teddy or Franklin), Emerson, Homer, Spinoza, Einstein, Aristotle, Socrates, etc.

Case 2. A majority of students in a particular classroom wish to open the school day with a prayer common to both Jewish and Christian traditions.

2a. This may meet the entire class needs. Otherwise 1c and 1d may be also be applicable for this case.

Case 3. A majority of the students are Muslim:

Same as Case 1, except that the prayers of 1a and 1c are reversed.

Case 4. A majority of students simply wish to open the school day with a moment of silence during which each student can silently recite his/her own specific prayer.

A mosaic is a lot more beautiful than a melting pot and possible more lasting and possible a better role model for the rest of the World. Including the Middle East. Remember the Aliyah of Mizrachi Sephardic (Mediterranean area) Jews to Israel and the attempts to make them into Secular Ashkenazim?

An Ethical Humanist may claim pity for the living, but we religious people, who perform time-honored rituals regularly, regardless of the exact theological content, and even when the theological content may not precisely mirror our deepest thoughts, demonstrate pity (rachmanut) for the living, pity and honor for those who passed, and affirm and practice hope for the future.

A music conservatory was planning its graduation exercises, and a group of secular professors demanded the President remove the opening prayer from the schedule, since they regarded it as religious coercion. The President reflected on the long history of the use of an opening prayer and the sorrow with which its omission would bring to the hearts of the religious professors. In the end, the exercises opened with a beautiful sung Psalm with the student choir and both the secular and religious teachers were happy. Perhaps music is an even better solution (actually the late composer Daniel Pinkham’s idea) than the first method I’ve proposed.