Rabbi Sacks, Community, and Times of Crisis

While the Jewish people worldwide and those dwelling in Zion are no strangers to acts of terror, the scope, brutality, and much of the world’s tacit approval of the barbaric murders inflicted on Simhat Torah has reached levels unparalleled since the Holocaust. “Since the Holocaust” . . . I never thought I would have to utter those words to describe an atrocity in my lifetime.

While the Jewish people worldwide and those dwelling in Zion are no strangers to acts of terror, the scope, brutality, and much of the world’s tacit approval of the barbaric murders inflicted on Simhat Torah has reached levels unparalleled since the Holocaust. “Since the Holocaust” . . . I never thought I would have to utter those words to describe an atrocity in my lifetime.

I am anxious about an uncertain future and feel lonely as much of the world vilifies Israel and the Jewish people. I find that these feelings are now the backdrop of many of our lives. While Israelis fight on the battlefields of Gaza, we are all wrestling with the emotional agony of this war. How can we channel our fraught and anxious emotions in productive ways so that we continue to be stable and even resilient? How do we find spiritual nourishment in these times of suffering? The wisdom of Rabbi Jonathan Sacks and contemporary psychological research teach that one way to contend with our pain is through embracing community.

R. Sacks emphasized the importance of community throughout the corpus of his writings. R. Sacks believed loneliness was a “defected state associated with sin.” For R. Sacks, emuna (faith) centers on “the redemption of solitude, the antithesis of being alone.”[1] Community is essential to religious life and the “human expression of Divine love.”[2] It is specifically in the presence of others where we are able to encounter the presence of God.

In addition to enhancing Jewish religious life, according to R. Sacks, communities are integral to overall well-being. In Morality, he distinguished between a community and a crowd:

We are not made to live alone. Not only is the unprecedented atomisation of modern life bad for our health and happiness. It is also dangerous because it makes us vulnerable to the dangers that lie ahead: turbulence, change, unpredictability. When the environment changes, people who are members of strong and diverse groups are at a huge advantage. They contain people with different strengths, variegated knowledge, diverse skills, and by working together they can negotiate their situation with effectiveness and speed. They have collective resilience. A crowd of disconnected individuals does not have that strength.[3]

A crowd is a mass of disconnected individuals in close proximity to each other but who share little together. A community is the unity of a people with shared values and vision. Community is integral to our health and happiness.

R. Sacks articulated what psychological studies have repeatedly shown. Supportive social relationships are associated with reduced risk of mortality and mental illness, drug addiction, and suicide. Belonging to a community is associated with improved physical and mental health by providing not only a buffer against the adverse effects of isolation and stressful events, but also as a source of positive experiences which cultivate resilience and growth.

The inverse has also been shown to be true. Loneliness is associated with a myriad of mental and physical health risks. It is estimated that social isolation has the equivalent negative health impact to smoking 15 cigarettes a day or having alcohol use disorder. Sadly, much of the Western world is experiencing what researchers have labeled the Epidemic of Loneliness. “It is not good for Man to be alone” (Gen. 2:7) has never been felt more acutely than now.

The benefits of community can be understood in light of Social Identity Theory, which suggests that group membership becomes incorporated into one’s sense of identity. When one joins a group, his or her psychological needs, like belonging, self-esteem, control, and meaning are fulfilled. The group expands an individual’s sense of self and offers a greater reason to live. When an individual becomes part of a community, the community becomes part of the individual as well.

Connecting to a community has even greater significance during times of turmoil. When a person is suffering, the very act of joining a group of empathetic listeners can alleviate individual pain. This is the foundation of group psychotherapy. The sufferer no longer feels isolated, but rather comforted when in the presence of individuals on a similar journey. Bill Wilson, the founder of Alcoholics Anonymous, discovered the panacea of what he called “mutuality” when he encountered an irresistible urge to have a drink just months after becoming sober. Before he succumbed to a setback, he thought to himself, “No, I don’t need a drink—I need another alcoholic!”[4]

In addition to the personal benefit of being part of a group, in Judaism, we believe that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. Rabbi Soloveitchik, notwithstanding his belief that loneliness is endemic to the experience of the man of faith, acknowledges the cumulative power of community:

In particular, Judaism has stressed the wholeness and the unity of Knesset Israel, the Jewish community. The latter is not a conglomerate. It is an autonomous entity, endowed with a life of its own…. However strange such a concept may appear to the empirical sociologist, it is not at all a strange experience for the Halachist and the mystic, to whom Knesset Israel is a living, loving, and suffering mother (“The Community,” 9).

The Jewish community is one living entity. We may be comprised of separate physical bodies, but we are spiritually united. “The people of Israel among the nations is like the heart in the body,” writes Rabbi Judah Halevi. “The heart is sensitive to the slightest trauma” suffered by any part of the body. The Jewish heart is acutely aware of the well-being of the rest of the Jewish People.

Being part of a community carries responsibility, and consequently meaning, as well. As a family, we must do our utmost to help our brothers and sisters in their times of need. Prayer in the plural, for the communal collective, is a halakhic imperative through which we recognize our deepest desires are not limited to ourselves (Berakhot 30a). When one of us is in pain, we all suffer. This idea is bolstered by a growing body of research which suggests that when one gives to the community, one receives a deep sense of meaning in return. R. Sacks echoed this sentiment when he wrote, “[m]eaning involves the acknowledgment of a world beyond the self. An individualistic, I-centered culture will be one in which people struggle to find meaning.”[5]

Just as we are responsible to the living Jewish community horizontally, we are endowed with the obligation of carrying the torch vertically, from our ancestors downwards to our descendants. By participating in our shared ancient rituals, we keep the fire burning. We not only enjoy its warmth, but through each and every Jewish act we add more fuel to the flame. We all play an integral role in the story of the Jewish people, as R. Sacks wrote using one of his most evocative metaphors:

Every Jew is a letter. Each Jewish family is a word, every community a sentence, and the Jewish people at any one time are a paragraph. The Jewish people through time constitute a story, the strangest and most moving story in the annals of mankind.[6]

God, too, as it were, has a unique love for Jewish unity. The famed sixteenth-century Safed mystic, Rabbi Isaac Luria, writes that when friends listen to each other with humility and openness, Divine mercy is aroused.[7] According to some commentators, this was an integral aspect of God’s decision to redeem the Israelites from their servitude in Egypt.[8] Similarly, according to rabbinic tradition, it was only when we united “as one person with one heart” that God deemed us worthy of receiving the Torah (cf. Rashi, Exodus 19:2). God’s love of unity is also expressed in His disdain of discord. The Talmud records that the Second Temple was destroyed on account of “baseless hatred” between one Jew and another (Yoma 9b).

Like a parent whose deepest desire is to create a home where the children love each other, God seems to value our comradery above all else. If this was true then, it is sure to be true now. Not only does community improve our physical and mental health, but it is the prism through which God bestows us with His mercy.

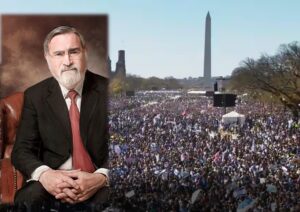

“We can face any future without fear so long as we know that we won’t face it alone,” taught R. Sacks. When Israel is at war, we must join together. For those far from the front in the Holy Land this may mean attending a rally, praying with others, joining a group packing supplies for our soldiers—and foremost suffering the pain in our hearts of the wounds delivered to the body of communal Israel. When we say there is strength in numbers, we do not only refer to how our message appears to others. We, too, are strengthened when we are part of a community.

Rabbi Marc Eichenbaum is a doctoral student in the Ferkauf School of Psychology and the Rabbinic Researcher for the Sacks-Herenstein Center for Values and Leadership.

[1] Future Tense: Jews, Judaism, and Israel in the Twenty-first Century (Schocken Books, 2012), 18.

[2] Celebrating Life: Finding Happiness in Unexpected Places (Bloomsbury, 2019), 149.

[3] Morality: Restoring the Common Good in Divided Times (Hodder & Stoughton, 2020), 35.

[4] Ernest Kurtz and Katherine Ketcham, The Spirituality of Imperfection: Storytelling and the Search for Meaning (Bantam Books, 1993), 84.

[5] Morality, 251.

[6] A Letter in the Scroll: Understanding Our Jewish Identity and Exploring the Legacy of the World’s Oldest Religion (The Free Press, 2004), 39.

[7] Shaar HaPesukim, Sefer Shir HaShirim.

[8] See, for example, Maharal, Gevurat Hashem, ch. 60.