Rav Kook’s Post-Modern Hanukka Miracle

Are we Jews? Are we Greeks? We live in the difference between the Jew and the Greek, which is perhaps the unity of what is called history. We live in and of difference, that is, in hypocrisy… (Jacques Derrida, “Violence and Metaphysics”)

Amid a discussion of laws of the Hanukkah candles, the Talmud turns to the question of the basis of the holiday. The rationale it provides is unattested in prior literature.

What is Hanukkah? The Sages taught [in Megillat Ta’anit]: On the twenty-fifth of Kislev, the days of Hanukkah are eight. One may not eulogize on them and one may not fast on them. When the Greeks entered the Sanctuary they defiled all the oils that were in the Sanctuary. And when the Hasmonean monarchy overcame and emerged victorious over them, they searched and found only one cruse of oil that was placed with the seal of the High Priest. And there was [oil] there to light [the Temple menorah] only one day. A miracle occurred and they lit from it eight days. The next year [they] instituted and made them holidays with hallel and thanksgiving (Shabbat 21b).

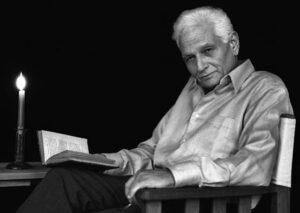

In his Ein Ayah commentary to Ein Yaakov, the compilation of the narrative (“Aggadic”) passages of the Talmud, R. Abraham Isaac Kook (1865-1935) offers a novel allegorical understanding of the Talmud’s choice to spotlight this particular incident (Ein Ayah 2:11 to Shabbat 21b). The passage is remarkable at face value, and on closer inspection, may represent some of the most interesting insights in Western philosophy, and, indeed, might have presaged some of the foundations of the discourse of postmodernism in the decades following its composition.

In his Ein Ayah commentary to Ein Yaakov, the compilation of the narrative (“Aggadic”) passages of the Talmud, R. Abraham Isaac Kook (1865-1935) offers a novel allegorical understanding of the Talmud’s choice to spotlight this particular incident (Ein Ayah 2:11 to Shabbat 21b). The passage is remarkable at face value, and on closer inspection, may represent some of the most interesting insights in Western philosophy, and, indeed, might have presaged some of the foundations of the discourse of postmodernism in the decades following its composition.

In the 18th century, thinkers such as Heinrich Heine and, following him, Matthew Arnold (in his 1869 Culture and Anarchy), spoke of a dichotomy between Hellenism and Hebraism. In the century and a half since Arnold, this dichotomy has been problematized, if not entirely repudiated.1 Rav Kook recognized that it was impossible to speak of a (post-Biblical) Hebraic culture that is clearly distinct from the Hellenic. Hellenism supplied a new language – not merely the Greek loanwords that pepper Rabbinic Hebrew, nor the forms of rhetoric at play in Rabbinic literature, but new conceptual possibilities that added novelty or definition to what the Bible left obscure or unsaid. Examples include the idea of a kosmos or ‘olam; the sanhedrin; the succession list/chain of masorah; and even the taxonomic abstraction that made the systemization of Jewish law – the Mishnah – possible.

One can, for the most part, find parallels to Jewish ethics and morality, theology, dogma, and even narratives in the Greek corpus. To be sure, some Hellenistic content was rejected;2 and philosophy as such was mostly not engaged by the classical Rabbis.3 But the Greek philosophic manner of thinking was inescapable, and its influence was indelible.

Rav Kook notes that the problem is even more acute when Hellenistic ideas infiltrate the “sanctum” of theology. In the Christian world, the project of synthesizing Biblical theology with Classical Greco-Roman philosophy was known as Scholasticism, and it held Christian thought in its sway throughout the Medieval period. In the Islamic world, from the Abbasids forward, this movement found Arabic cognates in kalam and falsafa; and in Medieval Jewry, the Sephardic Rishonim fully engaged Classical philosophy, and the synthesis of Torah and ancient Greek philosophy reaches its zenith in Maimonides’ Guide for the Perplexed.

From Luther forward, Scholasticism came under withering critique, which intensified as philosophy entered the modern era. The God of Greek philosophy was too transcendent, too impersonal, and really incompatible with the fiery, live God of revelation that emerges from the pages of the Bible. This critique was voiced by Jewish thinkers such as Samuel David Luzzato and R. Samson Raphael Hirsch in response to the Haskalah; later, in the world of general philosophy, it was most sharply articulated by Martin Heidegger, who relegated all prior systems of metaphysics since (at least) Plato to what he disparaged as “onto-theology,” the admixture of the study of Being with the study of God. By fitting God into a neat scientific explanation of the Being, God’s mystery is dissipated, He becomes an abstraction that is impossible to worship, and man narcissistically asserts his control over the Divine just as technologically-oriented man has subordinated everything else in God’s world to his selfish use.

Rav Kook, in contrast to figures such as Luzzatto and Hirsch, defended Maimonides and his Guide. However, he goes beyond Luzzatto and Hirsch, and prefigures Heidegger in describing the effect of Greek thinking, of Classical philosophy, upon Jewish theology. For Rav Kook too, metaphysics inevitably engenders onto-theology, and the latter immediately leads to the chilling of devotion and the subordination of the Divine to human calculative thinking. The effect of contact with classical thought is the transformation of theology so that Pascal’s “fire” cannot burn, that God becomes an abstraction to Whom it is impossible to pray or sacrifice, “fall to [one’s] knees in awe nor play music and dance” – the Unmoved Mover’s commandments are removed from any hope of pious fervor; if mitzvot are seen to come not from God, a melekh hai ve-kayam but an “Uncaused Cause” or “Ground of Being” ordered by men to anchor their favored conceptual system, Torah laws can only be observed as mitzvot anashim melumadah, by rote.

Rav Kook outlines the crisis:

“When the Greeks entered the Sanctuary they defiled all the oils that were in the Sanctuary”…. Israel needs to keep its spirit and heart on guard – if sometimes one sees a good thing, an upright behavior and the correct manner of inhabiting the world among the nations and takes them to bring them within its borders, he must see to it that the spirit of the nations as a whole will not enter into the content of his inner life, because when the spirit of the nations enters into the life of Israel it becomes an unstoppable force. Then the spirit of Israel will already be pushed from its place and a stranger will sit on its throne, because the spirit of Israel needs to be firm and steadfast in the heart… But when the spirit of Greece burst forth to enter the depth of the holiness of Israel, to impose a new form upon the Israelite spirit, and instill new passions in the interior of the Israelite life according to the Greek measure, once they entered into the sanctuary, they defiled all the oils in the sanctuary; not only did they invalidate the essence of those views and qualities that were marred by the contact with the dissolute Greek culture, but rather the matter affected the entire system of doctrines and traits, the deeds and the teachings…, lowering them from their sanctity and to prevent their good and holy effect on the people of God… But the weak-minded will take comfort in that they may make the best of what remains, and there are still a great multitude of true teachings and laws of life before them, in which they will live despite the absence that is found in the place that meets the strange spirit that already penetrated to the depth of their inner life. We learned that once the Greeks had merely entered the sanctuary, once the foreign spirit had penetrated all the way interiorly, unto the life of Torah and holiness, to damage them, to change them almost according to their own nature, all the oils in the Temple had already become defiled. The spirit will no longer spare a single corner, and like the viper’s venom, the foreign and corrupting current will spread throughout the nation’s body, rendering it rancid, its faith and its innocence, and every holy anointing oil from the oil of the Torah, the power that sanctifies and illuminates our darkness in all situations, behold, they will defile it, until if specific acts from the Torah remain in the hands of these who are tempted by a foreign spirit, they will be as mitzvot anashim melumadah, rote performances (“taught by the precept of men,” Isaiah 29:13), and for the most part the ancillary matters will remain, and it will not be possible for the power of the defiled oil to shine a holy light.

What Rav Kook appears to be saying is that the Greek way of thinking, once applied to “the domain of the holy” – metaphysics, which defines Being and the place of God in the universe – inevitably and inexorably damaged the Biblical Jew’s sense of God-consciousness. Once we perceive God through the spectacles of the metaphysician, the force of Jewish observance is vitiated, and religious fervor becomes impossible.

What is to be done? It may be impossible to reconstruct a Jewish theology that preceded contact with the Greek world. In a genuine Biblical theology, Divine nearness was experienced as palpable, present in and coloring the manner of the individual’s approach to the world; as both sovereign and father, a very real presence whose revelation – the “disclosure of Being” – was understood to have normative consequences.

Hermann Cohen, writing from a neo-Kantian perspective, already noted that the relationship of the root of the Tetragrammaton with that of “being” is “a philological fact,” and concludes that “Only God has being. Only God is being,”4 but his understanding of being is situated within the onto-theological system which displaced all that came before. When the Greeks mistook “Being” for beings, God as the Hebrews knew Him was displaced from the limits of the world of human thought (as Wittgenstein set the limits of one’s world). His name was no longer simply ineffable but now even “unsayable,” “nonsense” in Wittgenstein’s sense of the term, not merely in Greek but in Second Temple Hebrew, whose vocabulary adopted Greek (and Aramaic) lexical semantics.5 The effect of the linguistic shift is reflected in one version of the Septuagint legend (Massekhet Sefer Torah 1:6): “Seventy elders wrote the Torah in Greek for King Ptolemy, and that day was as ominous for Israel as the day whereon the Israelites made the Golden Calf, for the Torah could not be adequately translated.” In the Megillat Ta’anit Batra, we even find a fast day assigned to this calamity: “On the eighth of Tevet, the Torah was written in Greek in the days of King Ptolemy, and darkness came to the world for three days.” In a sense, the Greek “exile” was worst of all – it displaced Jews not of their land, but rather of their Ground of Being.

Second Temple Jews seem to have been aware of a rupture6 — 1 Maccabees 9:27 acknowledges that prophecy had ceased. Greek sciences and sensibilities rendered the very consciousness that allowed for revelation a dead letter.

What, then, is left for Hanukkah to celebrate? Rav Kook continues: there is hope.

“And when the Hasmonean monarchy overcame and emerged victorious over them, they searched and found only one cruse of oil that was placed with the seal of the High Priest. And there was [oil] there to light [the Temple menorah] only one day. A miracle occurred and they lit from it eight days.” The defilement of the oils, the corruption of the traits and doctrines, that came to the camp of Israel due to the strengthening of the Greeks and their rule, is the most terrible trouble that touches the soul of the nation.… Every person from Israel has a priestly side, because in their entirety they are a kingdom of priests and a holy nation. The inner desire, for the holiness of life and for the knowledge of the Torah and to walk in its ways, is hidden in the depths of the Israelite heart… even deeper in the heart resides the light of the Israelite soul, wherein is hidden the inner connection of the Israelite person – which appears in all of its glory in the nation as a whole – with the fundamental faith in the name of the Lord, the God of Israel, and the strong and venerable desire not to be separated from their (metaphorical) ancestral home, from faith as a whole. This is the inner world of the Israelite, whose model among the whole [of the people] is the High Priest who enters innermost to serve in the Holy of Holies on the day that is holy and differentiated from all the workings of material life. That small cruse that is emplaced with the seal of the High Priest, the Greeks will not be able to defile, to uproot from all of Israel their deep inner connection with the Lord God of Israel, this, all the powerful and mighty will not be able to do this, “Many waters cannot quench love, neither can the floods drown it” (Song of Songs 8:7).… This is the wondrous power that inheres in the spark of the hidden light, that even though it finds before it ways of life that are opposite to its content, doctrines that spread out that stand opposing it, without the knowledge of those who hold these doctrines that in this they are going in the opposite direction from that which is hidden in the deepest interior of their souls. And behold God’s hand will be revealed by His acts with this people that He has chosen for Himself, and the little spark will ignite a flame and pull up from their root all the foreign ways of life, and all the contrary doctrines that have been stacked upon it in piles, and it will spread over all the ways of life to return the heart of Israel to their Father in Heaven, until the forces of life in practice that are already leading in the direction of the Torah and the commandment will suffice to revive Israel and shine their light, until the passage of all of the present time and until the arrival of the new era of “a new light upon Zion,” until the coming of the year of redemption and the day of desire for God. “And the Redeemer shall come to Zion, and unto them that turn from transgression in Jacob” (Isaiah 59:20).

Here, Rav Kook teaches that “authentic” Jewish ways of life and doctrines may have, for now, been completely replaced by their opposite. But in spite of the imposition of its opposite – perhaps even because of the imposition of its opposite – and its total absence, the trace of the cleaving unto God of the ancient Israelite faith persists; it haunts the Hellenized lives we lead, and will assert itself by uprooting the alien ways.

“The next year [they] instituted and made them holidays with hallel and thanksgiving”.… Therefore, after a year, they saw that this protection that is from the hand of God to Israel, due to the inner treasure of holy anointing oil of the foundation of the faith, this is worthy of being established for generations, because the war of the arrogance and the aggression of the Greek spirit has not yet ended, and we will forever need the power of the internal oil, in which foreign contact does not dominate, to be a shield – therefore they established [the holiday and its observances]. Even regarding this they determined, that we will not only receive the bad, from this meeting of the spirit of Greece that enters Jacob’s tabernacle…. but rather this is the measure of the Omnipresent Blessed be He in directing His world generally, and directing the people of Israel specifically, that all those things that oppose and seem bad in their reality, they themselves cause greater glory to the power of goodness and truth. Therefore the encounter with Greece, when it has finished its process of surrendering completely before the glory of God, who is the stronghold of Israel, it will still be used with all its powers to add glory and strength to the Torah of truth and to magnify the name of the Lord, God of Israel in the world, the beauty of Japheth will be established in the tents of Shem, to expand and perfect, glorify and raise the splendor Torah and pure fear of God, which is planted upon the mountains of Israel. Therefore, these days are worthy to be set aside as holidays of praise and gratitude.

In this last section, Rav Kook adds a new element – apparently later, after our native faith has reasserted itself, there will come a more balanced reality. Hellenism and Hebraism will coexist with the binary opposition effaced, in a messianic era to come.

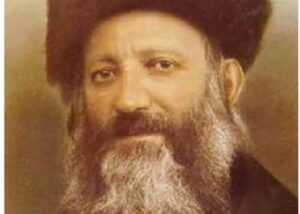

Rav Kook’s approach anticipates many themes later articulated by Jacques Derrida (1930-2004), arguably the best-known postmodernist thinker. Derrida also subscribed to Heidegger’s critique of onto-theology, but suggested a very different “resolution” to the issue.

In his 1967 work Of Grammatology, the French-Algerian Jewish intellectual upended the logocentric articulation of the Platonic ideal – that words, or signifiers, correspond to a signified, an objective reality – by showing that signifiers actually always rely upon other signifiers, and meaning derives not from some real present object but from the manner in which it contrasts with other words, what he termed différance. Any use of a term always bears traces of its opposites. In its use of terms, texts constantly privilege one attribute and suppress the other in binary pairs; in a commonly used example, the term “house” attains meaning only in its contrast with opposites like shed, mansion, hotel, building,– and in the choice to use the word “house” these other possibilities are suppressed. Texts are full of the subordination of one choice in the binary to another. One can also find traces of “dead” ideas from the social past among that which textual choices subordinate. Derrida innovates a concept of deconstruction, in which textual hierarchies are first reversed so that the binary can be identified, and then the tensions in the text are revealed to coexist. For Derrida, all of reality can be understood as a text. Derrida adapts the Jewish messianic idea to what he calls “messianicity,” a “democracy to come” in which ideas and groups will coexist in equality, without subordinating one another.

In Rav Kook’s description of the Hanukkah miracle, a Derridean read seems to suggest itself immediately. Jewish Hellenism is built upon the ruins of Biblical consciousness; Greek onto-theology flourishes from the death of prophecy and the primordial openness to being. But the very existence of these binaries guarantees that the trace of the former remains, and its specter haunts our Hellenized Jewish lives. In time, Derridean “deconstruction” will occur: first with the violent reversal of the Hellenism-Hebraism binary, but then, in messianic time, with a more democratic, ambiguous reality in which the binaries will dissolve, and Hellenism and Hebraism will coexist.

Fascinatingly, Rav Kook’s symbol for the Jewish essence – the High Priest entering the Holy of Holies on Yom Kippur – illustrates Derrida’s theory of différance perfectly. Sanctity in Judaism depends upon difference – time, place, and person set apart in binary differences from profane, or less-holy. But at the center around which they all converge, which their apogees meet on Yom Kippur, no Signified can be seen. The empty space between the cherubs is even exempted from the rules of physics; the ark takes up no space at all (Yoma 21a; Megillah 10b; Bava Batra 99a). At the heart of the inner sanctum, one will not find a Signified, but only a void surrounded by signifiers, as a template for the structure of the rest of our perceived reality.

Hanukkah’s metaphoric revelation is much like Derrida’s trace, something that is not represented in words in the text that we read (for there is no Biblical book of Hanukkah), nor in the lives that we lead, rather it can be detected in what that text suppresses. The Hanukkah fire of Biblical God-consciousness is a wordless “book” that, in its very absence, has profoundly influenced our Hellenized minds for millennia, thus remaining aflame until the ultimate messianic restoration of balance to metaphysics.

Is this a legitimate reading? As Derrida writes about a theological reading of his own work, “This will always be possible; who could forbid it?” (Positions, 539).

Rabbi Dr. Aton M. Holzer is Director of the Mohs Surgery Clinic in the Department of Dermatology, Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center, and is an assistant editor of the RCA Siddur Avodat HaLev.

- Louis H. Feldman, “Hebraism and Hellenism Reconsidered,” Judaism 43:2 (1994), 115. Alan T. Levenson, “Invidious Distinctions: Hebraism and Hellenism in Heinrich Heine and Matthew Arnold,” Jewish Quarterly Review 110:1 (2020), 102-126.

- Louis H. Feldman, “How Much Hellenism in Jewish Palestine?” Hebrew Union College Annual (1986), 83-111.

- See discussion in Eliezer Segal, “‘The Few Contained the Many’: Rabbinic Perspectives on the Miraculous and the Impossible,” JJS 54 (2003), 273-282.

- Hermann Cohen, Religion of Reason Out of the Sources of Judaism, trans. Simon Kaplan, 2nd ed. (Scholars Press, 1995), 39 and 41.

- Daniel Boyarin, “Bilingualism and Meaning in Rabbinic Literature: An Example,” in Fucus: A Semitic/Afrasian Gathering in Remembrance of Albert Ehrman, Yoël L. Arbeitman, ed. (John Benjamins, 1988), 141-151.

- Ari Mermelstein, Creation, Covenant, and the Beginnings of Judaism: Reconceiving Historical Time in the Second Temple Period (Brill, 2014).

Thanks to Professors Gabriel Danzig, Ranon Katzoff, Rabbi Arie Folger and Dr. Alan Jotkowitz for their insights and comments. Thanks also to my daughter Rivka, for her feedback on an earlier draft.