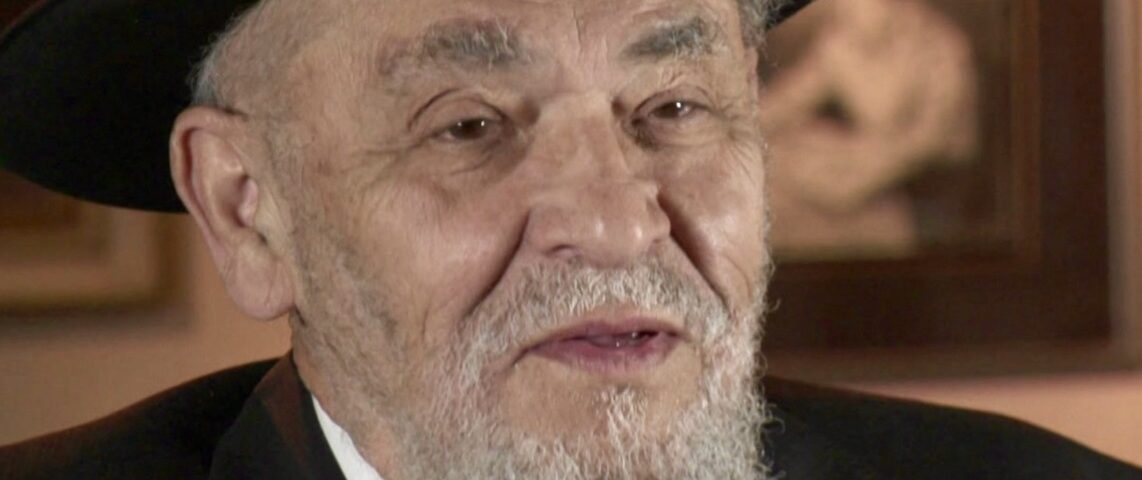

Remembering a Regal Rabbi

TRADITION mourns the recent passing of Rabbi Dr. Moshe D. Tendler zt”l, 95, longtime Rosh Yeshiva and professor at Yeshiva University, and frequent contributor to our pages. This tribute by Rabbi Reiss is the second in a series of essays exploring Rabbi Tendler’s legacy. Read the concluding installment here.

Growing up in the Community Synagogue of Monsey, I had no difficulty comprehending the Talmudic expression, “Man malki? Rabbanan” (see Gittin 62a). Rabbi Dr. Moshe Tendler zt”l was the epitome of rabbinic royalty, blessed with an aristocratic aura, eloquent speech, regal bearing, and nobility of spirit. Whenever he spoke, regardless of how unpopular some of his opinions might have been in certain circles, his word was viewed and received by us at Community Synagogue as genuine Torah mi-Sinai.

Growing up in the Community Synagogue of Monsey, I had no difficulty comprehending the Talmudic expression, “Man malki? Rabbanan” (see Gittin 62a). Rabbi Dr. Moshe Tendler zt”l was the epitome of rabbinic royalty, blessed with an aristocratic aura, eloquent speech, regal bearing, and nobility of spirit. Whenever he spoke, regardless of how unpopular some of his opinions might have been in certain circles, his word was viewed and received by us at Community Synagogue as genuine Torah mi-Sinai.

There was good reason for his community members to both love and respect him. Every shiur that he delivered, such as his weekly Shabbat class on Rambam delivered before the Torah reading, was filled with erudition, wisdom, innovation, and insight. He masterfully wove together the classical opinions of Rishonim and Aharonim, the rulings of his “shver” – his father-in-law, Rav Moshe Feinstein zt”l, the twentieth century’s preeminent halakhic decisor, and his own perspicacious insights regarding medicine, science, psychology, and sociology. Rabbi Tendler spoke our language, that of the modern world, and in the process taught us how to speak his language, that of timeless Torah.

My own affinity for Torah u-Madda, as a student at Yeshiva University and its Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary, and later as a practicing attorney and as the Dean of RIETS, was in large part influenced by Rabbi Tendler, who regularly synthesized his Torah knowledge with scientific prowess. His worldly renown as a bioethicist with a doctorate in microbiology evoked for me the verse “the Torah is your wisdom and your understanding in the eyes of the nations” (Deut. 4:6) – which the Talmud understands as referring to the admiration by the nations of the world of Torah scholars who possess a mastery of the scientific universe (Shabbat 75a).

In addition, Rabbi Tendler taught me how to harness a healthy sense of humor for the purpose of teaching Torah. Once, when he was describing the requirement for a husband to go to work to support his wife, he quipped, “a wife marries her husband for better or for worse, but not for lunch.” He explained his opposition to retirement by explaining that “man was made to toil” (Job 5:7), and that retiring was all about having nothing to do and therefore getting tired, taking a nap, and then getting “re-tired” and taking another nap, and then getting “re-tired” again, and so on. Of course, his numerous one-liners and witticisms were legendary.

On Yom Tov afternoons Rabbi Tendler would give classes on the Megillot of each festival, combining the textual explanations of the verses in Shir Hashirim, Ruth, and Kohelet, with midrashic insights that penetrated my soul. I remember lamenting together with a learned member of the shul, who also served as a partner in a major Wall Street law firm, that Rabbi Tendler’s shiurim on the Megillot were such a magnificent blend of prose, poetry, and philosophy that it was a terrible shame that they weren’t recorded for posterity. He had a brilliant grasp of the human psyche, and a beautiful way of expressing it through Torah sources.

He once offered his interpretation of the famous story of the prospective proselyte who came before Hillel and asked to be taught the entire Torah while standing on one foot. Hillel responded, “That which is hateful to you do not do to others,” adding, “the rest is commentary – go learn it” (Shabbat 31a). Rabbi Tendler explained that the proselyte desired to accept only the “one foot” of the interpersonal laws of Judaism, which he found to be ethical and fulfilling. However, he didn’t want to accept the other foundational “foot” of the ritual laws between man and his Creator. According to Rabbi Tendler, Hillel responded that while it is correct that our main focus is upon observing the ethical laws, one cannot stand on that one foot alone without learning and practicing the ritual laws between man and his Creator, because this is the “commentary” that provides the framework for appreciating what constitutes ethical behavior as a whole, as opposed to man-made laws which are always subject to the whims of change. As I recall, he gave as an example the hospitality of Abraham, which was carefully calibrated based on Divine principles (see Rashi, Gen. 18:4), as opposed to the that of Lot, who lacked a Divine compass, and therefore was prepared to volunteer his daughters to be violated by a marauding mob for the sake of protecting his guests. It seemed like there was nobody with a better sense of defining Jewish ethics in the modern age of science, medicine, and technology than Rabbi Tendler, who understood that the source of all ethics is a clear and unshakable Torah worldview.

For his two major derashot of the year, on Shabbat Shuva and Shabbat HaGadol, Rabbi Tendler would post the list of his numerous sources a week in advance of the shiur. The shiur itself, which could easily last for at least an hour and forty minutes, was preceded by a preparation session, typically delivered by one of his sons, to prepare the congregants for the derasha. All together many congregants would happily devote close to three hours of the day to imbibe Torah from their beloved Rav. On Shavuot night, he would regale the congregation with non-stop shiurim from midnight until dawn, often choosing juicy topics of contemporary controversy.

Rabbi Tendler’s erudition in Torah was only matched by his well-known, but more often private and unheralded acts of kindness and charity, which he and his Rebbetzin a”h generously doled out with love and affection. If a congregant experienced a crisis of any sort, Rabbi Tendler was not only available, but became fully invested in resolving the crisis. There were numerous times that my family leaned on him for help in medical emergencies relating to both immediate and extended family members, and he not only furnished halakhic guidance, but proactively steered us to the best physicians, best hospitals, and best treatments. I cannot comprehend how he managed to devote so much time, patience, and care to our individual situations and those of countless others when he was also serving as a Rosh Yeshiva at RIETS and the chairman of the biology department in Yeshiva College.

When I was ten years old and suffered a serious injury after being accidentally hit in the head by a golf club, Rabbi Tendler was at my family‘s side practically around the clock. After I recovered from the initial life-saving head surgery to remove shattered bone and to repair my right eye, a second operation was scheduled a year later to insert a replacement bone above my eye. I still remember my conversation with Rabbi Tendler when he visited me at Mount Sinai Hospital right before the second surgery. He handed me a small, blue, hard-covered Sefer Tehillim as a gift. I told him that I was very grateful that I had survived the first surgery, but that I was nervous about this second operation, especially since I was already walking around with a literal hole in my head. “How can I be sure,” I asked him, “that I will also survive this surgery?” He smiled and said, “If Hashem has taken you this far, he is not going to give up on you now.” That was all the reassurance that I needed. I recited the Tehillim with a sense of inner calm and confidence, and thank God, the surgery was indeed successful. I made special use of Rabbi Tendler’s gift of that Sefer Tehillim many times in the ensuing years.

Over the years, I always remained close to Rabbi Tendler, and would often ask him for personal advice, particularly during my relatively long dating career. When I became engaged to my wife, he announced in shul that she was marrying “the world’s most eligible bachelor.” My wife still occasionally cites that comment to our Shabbat guests, so it clearly had its intended effect.

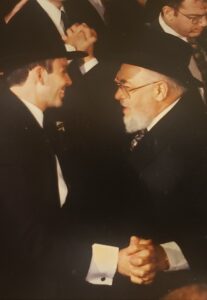

R. Tendler dances at the author’s wedding, 1999

In addition to being the mesader kiddushin at our wedding, Rabbi Tendler was present at the brit mila of each of our five sons, and he honored us by bestowing the name upon each of them. Although he didn’t personally name our daughter, when she was born eleven years ago, we did make sure to consult with him, as we did about many matters, concerning the name that we should give her. He advised us with his usual good humor about how a certain Yiddish name that we considered giving her would not go over well in the modern age.

My eldest son, Yehuda Dov, enrolled at Yeshiva University a couple of years ago. When I called Rabbi Tendler before Rosh Hashana that year, he immediately exclaimed, “What a tall, good-looking son you have!” Yehuda Dov recently had the privilege of attending the last bio-ethics class that Rabbi Tendler delivered at Yeshiva College, via Zoom, during the Fall semester of 2020.

One of the last times that I saw Rabbi Tendler in person was at the Siyum HaShas at MetLife stadium on January 1, 2020, shortly before COVID changed our world. I had the privilege of sitting a few rows behind him on the dais, and clearly remember how many people, much younger than him, made an early exit on account of the frigid temperatures. Throughout the entire event Rabbi Tendler, then aged 93, sat calmly and comfortably in the bitter, freezing cold, learning contentedly from a small Gemara that he caressed in his hands. Of all the stirring speeches that were delivered that day at the Siyum, his quiet, whispered one was, for me, the most powerful and inspiring of them all.

Rabbi Yona Reiss, a member of the TRADITION editorial board, serves as the Av Beth Din of the Chicago Rabbinical Council.