REVIEW: Bound in the Bond of Life

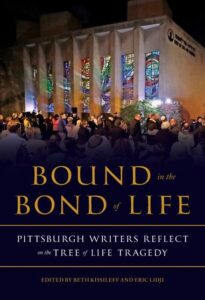

Bound in the Bond of Life: Pittsburgh Writers Reflect on the Tree of Life Tragedy, edited by Beth Kissileff and Eric Lidji (Univerity of Pittsburgh Press, 2020), 256 pages

On the day after the Pittsburgh synagogue massacre, at the end of October 2018, I received an email from a dear friend who is not Jewish: “We’re grieving with you. How are you doing?” I was amazed at her capacity not just to join me in my grief, but to realize so quickly – possibly before I did – the extent to which that grief was indeed mine, without even asking first whether I knew any of the victims. (I didn’t.)

On the day after the Pittsburgh synagogue massacre, at the end of October 2018, I received an email from a dear friend who is not Jewish: “We’re grieving with you. How are you doing?” I was amazed at her capacity not just to join me in my grief, but to realize so quickly – possibly before I did – the extent to which that grief was indeed mine, without even asking first whether I knew any of the victims. (I didn’t.)

It’s been three years since the shooting at the Tree of Life Synagogue claimed the lives of 11 shulgoers from three congregations and impacted the lives of countless others in countless ways. It’s been one year since the publication of Bound in the Bond of Life: Pittsburgh Writers Reflect on the Tree of Life Tragedy, a volume filled with numerous portrayals and perspectives on those impacts.

Why write a book like this, and why read it?

One of the editors, Eric Lidji, offers insight into the book’s title and intent in his Introduction. Originally part of Abigail’s bold statement to David (I Samuel 25:29) and since then a fixture of the Jewish mourning lexicon, the phrase “may the soul be bound in the bond of life” represents, he suggests, divine protection and also a charge to us to remember. “There is a sense within Judaism that the dead depend on the living,” through the mitzvot we perform and the Kaddish we recite on their behalf. “The bond of life is a vital and eternal connection between the dead and the living. It exists through our memory of them” (2). The goal of remembering that he describes, though, is actually more focused than memory alone: It is the aim of humanizing an event that could otherwise become just another item on a list. The goal is to not lose sight of the actual people who actually suffered, as the event fades into just another horrible antisemitic event and perhaps just another piece of support for whatever agenda one wishes to put forward.

An Afterword by co-editor Beth Kissileff alludes to some of the same ideas, and expands further. She compares the book to the Haggada, with its goal of bringing the experience to life and raising and perhaps answering questions, and hopes that reading it will be “like bumping into one of the family members of the victims” (234). She also describes the book as a sort of “virtual gathering place” and the experience of creating it “like a gathering of friends, getting together to swap stories and help each other through coping with the event” (237) as well as an opportunity for Pittsburghers to tell their own story, their way.

And so, this is not really a book about the victims, though most of the writers share at least something about at least some of them. It is rather a book about those who lived, about how they experienced and processed the horror and about what that means moving forward, for them and for the world. It is raw and heartbreaking, and also inspiring in ways I did and did not expect.

A recurring theme in the book is the interplay of connection and distance – who was and wasn’t there, who did and didn’t suffer an immediate loss, the difference (and perhaps overlap) between individualized pain and universal horror. Whose grief it is to feel, and whose to tell. Lidji shares that “As the story of Pittsburgh is increasingly told from afar, the editors wanted to create an opportunity for a diverse group of local writers to grapple” (3) with the many and varied questions raised by their experiences surrounding the shooting, near and nearer. “The contributors to this anthology had to find the authority to write about an attack that most of them did not experience directly. Again and again, closeness is where they find that authority” (4). Most of the writers reference the streets they do or do not frequent in Squirrel Hill, the congregants they did or did not know personally or through mutual friends; they talk about where they were when it happened and how their personal or professional lives colored their experiences of and after the shooting. They seek to legitimize their own reactions, to acknowledge the ways the grief is not their own (because they are new to Pittsburgh, or were away when it happened, or aren’t very Jewishly involved) and to demonstrate why and how it is a part of them anyway, to varying degrees. Some aim to justify their very presence in this volume, though they were invited to contribute by others who believed their contributions would be justified.

Multiple writers reference the concept of “concentric circles of grief” – those who were there, those who lost friends or relatives, those who live nearby, further and further out, to the farthest reaches of impact on all of humanity. This way of thinking about the event highlights the greater impact on those who were closest and at the same time grants legitimacy to a wide range of connections and reactions, whether local or not. None of the writers – despite their shared locality – experienced or processed the tragedy in exactly the same way, and none of us at a distance did either. But yes, the grief, unfortunately, belongs to us all. (Like many others, even at my own remove from the event and its victims, I felt connected, and shared thoughts in my own essay reacting to the shooting.)

As with the impact of the tragedy itself, the influence of the book will vary for every reader. The variety of perspectives shared includes a wide spectrum of religious observance and philosophy, adding to the sense that the book highlights both differences and similarities, distances and connections. Different perspectives and “takeaways” – insights, or practical calls to action – will resonate differently with each of us.

Highlighting that variety are the many different anchors – cornerstones for processing the tragedy, in an experiential or literary sense – on which many of the essays hinge. More than one focus on the eruv and what it does and doesn’t represent (like a fence protecting from outside threats), though in different ways. Susan Jacobs Jablow homes in on what it was like to observe Shabbat the rest of that day, focusing on her immediate family and waiting with dread until dark to contact or learn the fates of loved ones; Lisa Brush describes how she found comfort through her tango classes and community. My friend Rabbi Daniel Yolkut published two derashot he had delivered at his Orthodox Pittsburgh synagogue, Poale Zedeck; he anchored his contributions in Jewish texts and interpretation. I was intrigued to notice that among the many and varied essays in the book, the editors felt this one required a framing device of sorts, noting that “although the framework might be unfamiliar to some, his approach to reckoning with tragedy resonates broadly” (152). For me, coming from a point of reference similar to Rabbi Yolkut, his pieces were among those that felt the most familiar; realizing how foreign others would apparently find his approach was a stark reminder of how wide and varied the Jewish world is, and how varied our experiences and perspectives within this world that connects us despite our differences.

For me as a reader, the recurring theme of connection was among the most powerful elements – connections between people, between ideas, within and between varying beliefs and worldviews, between experiences. Connections that are obvious, and those that seem so tenuous as to be questioned by the very people claiming them. Connections next door, connections a few hours away, connections in spirit. Connections where they are least expected – like in the tango essay, which I found surprisingly moving and relatable despite my initial skepticism. I even noted some overlapping ideas between the description of how tango helped that writer cope and how my friend Rabbi Yolkut described finding “vessels” to help access divine comfort and a sense of blessing. Uncovering these unexpected connections is strengthening; perhaps, on some level, in the same way several of the writers describe feeling strengthened by the overwhelming support from strangers with their own senses of connection to the shooting. Hearing about others’ anchors – not just what anchors them, but their insights into how it does so – helps us understand and firm up our own anchors, as we realize they function in similar ways.

I was also particularly struck by the essays by journalists. There’s a popular perception of the media as a faceless, heartless entity that cares nothing for the human beings whose pain it lays bare, but only for the headlines. That may be an accurate portrayal of some, but the journalists who contributed to this volume laid their own pain just as bare. They describe the challenges, especially emotional, of covering mass tragedies, and how they managed to cope – and how they chose to ignore concerns about professionalism and allow themselves to cry alongside those they interviewed. They remind us that they too are merely human, working to broaden perspectives and help build meaning from pain. Alongside those of the other writers, their insights – often born of years of experience and having “seen it all,” until this one was different – provide important context and perspective with which to move forward as we dry our tears.

Bound in the Bond of Life was, as I expected, a hard book to read. It is not pleasant to be reminded of horror, to be pulled into multiple horrific experiences and the depths of emotional trauma. It also, at times, feels slightly voyeuristic to watch that trauma unfold in others; I had to remind myself that the writers invited me to observe and feel what they experienced, perhaps in the same way the writers themselves had to remember that they were invited to share their experiences. My reading, like their writing, is relevant and valuable in the larger picture of the experience and aftermath and memory of the Pittsburgh shooting. And in truth, despite the challenges in reading a book like this, I couldn’t put it down. The writing itself is phenomenal, and the grief is meant to be shared.

Sarah Rudolph, an editorial board member of TRADITION, is a freelance Jewish educator and writer in Cleveland, editor-at-large for Deracheha, and director of TorahTutors.org.

1 Comment

Has the reviewer, author, or readers thoght about the idea that nearly every Israeli family has a member 0r members, and/or frien or friens, taken from a similr trgwdy?