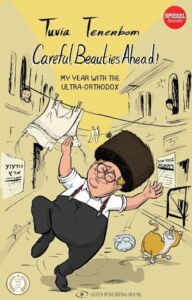

REVIEW: Careful, Beauties Ahead!

Review: Tuvia Tenenbom, Careful, Beauties Ahead! My Year With the Ultra-Orthodox (Gefen Publishing, 2024), 576 pp.

In an August 2024 appearance on The Franciska Show podcast, author Tuvia Tenenbom could not understand why his new book Careful, Beauties Ahead! My Year With the Ultra-Orthodox was not getting more traction within the United States Orthodox community. He was perplexed, given that—according to him—it was quite popular among Israeli Haredim.

In an August 2024 appearance on The Franciska Show podcast, author Tuvia Tenenbom could not understand why his new book Careful, Beauties Ahead! My Year With the Ultra-Orthodox was not getting more traction within the United States Orthodox community. He was perplexed, given that—according to him—it was quite popular among Israeli Haredim.

I cannot speak to the book’s popularity in Israel. However, in the United States, Orthodox publishing houses and their readers often prefer hagiography over objectivity. For the publishers from ArtScroll to Feldheim, Hamodia to Yated Neeman, topics around sexuality and intimate body parts are rarely, if ever, written about. Even something like breast cancer is referred to as “chest cancer.”

With that, a book like Careful, Beauties Ahead!, with its overtly sexual content, in addition to its uncomplimentary comments about Haredi rabbinic leaders, alongside its mocking of Litvak yeshiva culture, will likely not be found in Orthodox bookstores anytime soon.

Given Tenenbom’s hilarious comments and observations, the book would likely be shelved in a bookstore’s humor section. However, given the author’s astute insights about the year he spent in the world of Haredi Judaism in Israel, it could just as easily be placed in sections such as social studies, sociology, religion, and more.

Haredi life is a topic Tenenbom knows well, as he grew up in Bnei Brak in a well-respected Haredi family. Despite a traditional yeshiva education, he left religious observance at the age of 14. Many of his classmates and childhood friends today number among the elite of Haredi society.

The level of friendliness with these people is high, and Tenenbom writes about one of the greatest leaders of the Haredi world, calling him a weirdo and an idiot. Those few paragraphs are enough to get the book blacklisted.

In her noteworthy book Off the Derech: Why Observant Jews Stop Practicing Judaism (CreateSpace, 2005), Faranak Margolese observed that one of the primary reasons young people leave religious observance is that many of their serious questions about faith and belief remain unanswered. And that seems to be precisely the issue that led Tenenbom to leave observance.

For many who left observance, it was not just that their teachers left these questions unanswered; the students were mocked and shamed for simply asking them. For many students, asking challenging questions about their Talmud texts is rewarded with praise. However, asking legitimate and challenging questions about tradition and faith often results in shame and calling the student a heretic for even considering such a question. This seems to be Tenenbom’s unfortunate story.

One would think that someone who left the Haredi world due to legitimate and honest questions being mocked and left unanswered would only return to the Haredi world with a vendetta. Perhaps Tenenbom had a hidden agenda when writing this book. However, overall, the book paints an entirely complementary and, at times, almost apologetic view of that world. While Tenenbom left Bnei Brak behind over 50 years ago, it is eminently clear from the book that Bnei Brak never left him.

Tenenbom has a most interesting pedigree. He is a theater director, playwright, author, and founding artistic director of the Jewish Theater of New York. His books include I Sleep in Hitler’s Room, Catch the Jew!, and more. Tenenbom, however, has no formal training in sociology or anthropology, and yet the book is a fascinating and absorbing account of his year in Meah Shearim. His stories offer profound insights into the Haredi world and its lifestyles.

Tenenbom is a proverbial people person, always looking to engage those around him, whether walking the streets or at a Rebbe’s tisch. The downside to this approach is that the book focuses on a somewhat narrow aspect of Haredi society. Nonetheless, with its acerbic wit and insights into the human condition, while not an academic tome, does provide interesting insights. .

He incredulously finds that many people he meets do not know the core reasons for their faith or core religious practices. They can tell him instantly that something is forbidden, but when asked why, silence follows. The problem with this “man on the street” interview approach is that it produces very skewed results. Perhaps those who would agree to speak to an outsider like Tenenbom are not the most learned. And one shouldn’t extrapolate from his dialogues that Meah Shearim is composed of ignoramuses.

It’s worth noting that while many of Tenenbom’s observations are quite interesting, it’s possible that he may have suffered the same fate as Margaret Mead in Samoa. Derek Freeman wrote that Mead misunderstood the local culture and may have been misled by the inhabitants she interviewed. Her conclusions were ultimately flawed.

I am not saying that is necessarily what happened with Tenenbom. However, a lot has changed in Haredi society over the past half-century, since his exit in 1971. Remember, Tenenbom is a playwright, not an anthropologist.

A sign that he is not an anthropologist or sociologist and not getting samples that have statistical significance is evidence that most of the people he spoke with are male. It’s an almost intractable problem in a place like Meah Shearim, where married women talking with men is an anathema. As such, the reader does not learn very much about the women of Meah Shearim, their lives, or stories.

To some degree, then, the book reflects one aspect of the society it depicts: In Meah Shearim, women are effectively invisible, as they are prohibited from speaking to men and their images are absent from all forms of advertising.

And several chapters are dedicated to understanding the reasons for the leadership conflict within the Gur Hasidic community and its stringent and abstemious attitudes concerning sexual relationships (between man and wife). Politics, money and sex—always scintillating topics, and Tenenbom clearly enjoys writing about them.

As to the Gur conflicts, imagine riots in which angry mobs threw stones and bottles, vandalized property, and caused mayhem. That occurred when a breakaway Hasidic group split from the centralized Gur community. At the same time, others may have seen that as independence, Gur leadership saw it as sedition. Tenenbom writes of this internecine conflict with amusement and interest. The protagonists are the Grand Rabbi of Gur Yaakov Aryeh Alter and his cousin, R. Shaul Alter. The latter headed the Gur Yeshiva system until 2016 when the Grand Rabbi effectively laid him off. That led to the 2019 Simhat Torah brouhaha when R. Shaul took hundreds of followers to start a new sect. The drama began; families and businesses were destroyed, relationships terminated, excommunications issued, and more.

Gur also makes a particularly appealing target for someone like Tenenbom, given their approach to sexuality and women. Dr. Benjamin Brown of Hebrew University has researched the Haredi world extensively, and writes that these attitudes around sexual relations were developed as a pietistic ideal for the virtuous few, encouraging married men to limit to the minimum the frequency and modes of sexual intercourse with their wives. Today, Gur is one of the groups that has radicalized this ideal by imposing it on the community as a whole.

Tuvia Tenenbom (courtesy)

Tenenbom doesn’t just ask good questions; he’s also an excellent listener. During his copious conversations with different people, he listened more than he spoke (a trait of a good interviewer, researcher, or reporter) to understand them and get a feel for what they were going through and what was going on in the streets.

Food plays a significant role in the book (as it does in Haredi society; see under: Shtisel), with Tenenbom frequently visiting eateries and bakeries. He is effusive about the various delicacies he samples, and one wonders why, based on his culinary experiences, there are not more Glatt Kosher entries in the Michelin Guides.

While the book could be shelved in the humor section, that doesn’t mean his year among the Orthodox offer no insights. While many of these can be used for the betterment of the community, it is unlikely the Haredi world will consider his advice authoritative. He is an insider/outsider. He grew up amongst the people he writes about and speaks their languages. That allows him to understand them honestly, apparently making them comfortable with him. There is seemingly honest dialogue, yet while the communication flows naturally, are the Hasidim responding to him honestly, or giving him the responses he wants? Perhaps they are just humoring him as a curiosity and oddity. Did they know those schmuzen were going to be reporting in print?

But between the jabs at Litvaks and his enjoyment of Haredi cuisine, Tenenbom makes several insightful sociological and historical discernments every few chapters. These may be lost on the residents of Meah Shearim, or appear banal to familiar insiders, but can be interesting to his intended audience.

For example, the old and deep enmity between the Zionist movement and the Hasidim goes back hundreds of years. During World War II, he writes that members of the Jewish Agency gave his grandfather, who was a rabbi in a Romanian town, the opportunity to save himself and the community he led from the approaching Romanian Fascists. These Romanian Fascists were aided and guided by the Nazis, who were about to catch up with the Jews of his town.

The Jewish Agency offered to smuggle his grandfather and others of his community out of Romania and into the soon-to-be-formed state of Israel. Yet his grandfather incredulously refused the offer from the Jewish Agency, saying he would rather be with the Nazis than with the Zionists. Tenenbom writes, “Man’s reality is rarely logic’s best friend,” Relating his grandfather’s fate at the hands of the Nazis.

And yet we must ask if he was using someone to find the subjects he interviewed or taking a Gonzo journalism-type approach. A case in point is his meeting with Dan Shiftan, senior lecturer at the School of Political Science at Haifa University, to discuss Haredim. Shiftan is well known for his animosity towards Haredim.

Regarding the Haredi world, some scholars are much better, more qualified, and able to talk about the subject than Shiftan, whose expertise is security. Be it the aforementioned Benjamin Brown, Kimmy Caplan of Bar-Ilan University, or many others. Evidence that this is not an academic text, Tenenbom spends some time observing the hygiene of Shiftan’s apartment. And he concludes the chapter with a picture of an inordinate amount of trash piled in Shiftan’s kitchen.

Tenenbom is a sophisticated intellectual. However, an underlying issue with his methodology and approach is that he left the Orthodox world at age 14 with the questions of a 14-year-old. Theology, in general, and Jewish law, in particular, requires a certain level of intellectual sophistication, and that can only be gained by learning the texts with a sophistication greater than that of a 14-year-old.

The book contains scores of pictures of Tenenbaum on his outings and eating trips. One of the most touching pictures is with Rabbi Mordhe Gutfarb of the Badatz Eida HaChareidis, with him and Gutfarb learning from the Shulhan Arukh. Tenenbom quotes from the opening of that work: A person should get up with their night clothes on and not leave the bed naked. The rationale is that it is immodest to appear naked like that before the creator of the universe. Tenenbom admits that he does not understand the rationale of these laws. He asks what sense it makes to get out of bed with clothes since God can see us naked anyway. He notes that this was the type of question he asked in his youth, and he was told it was arrogant to ask such a question.

Far from being an arrogant question, it is a most reasonable one. Yet Tenenbom had the bad mazel to have teachers who needed much more patience for such questions. Had he taken the time to probe the deeper meaning of the laws he was learning with Rabbi Gutfarb, including philosophical commentaries that explain the inner points of the laws, these would have helped him understand God’s immanence. Had he spent the time to gain that deeper understanding, those regulations in the Shulhan Arukh would have made much more sense to him.

God’s profundity and the intricacies of halakhic reasoning take time to understand and master. That short meeting with Gutfarb raised the question, but certainly not long enough to get an adequate answer.

Towards the end of the book, we find Tenenbom venturing out of Meah Shearim to the bourgeois Baka neighborhood in southern Jerusalem. He meets with an American reform rabbi and her family and attempts to gain a perspective on Meah Shearim from a safe distance. He met her during the holiday of Sukkot and noted that her sukka was a rather depressing place. Given his love for food, he noted that the second-rate fare was fit for flies. It had very little taste, although it was healthy. Perhaps her worst trespass was that there was no Coke Zero, his drink of choice.

But what may be Tenenbom’s most astute insight in the book is what he noted when leaving her: that something big was missing, something beyond just the food or environment. And that something was called soul. What is a soul, he asks. Hasidim have it, and you feel it every minute you are with them, he tells us. It’s something that connects you with the heavens, with angels, and with God himself, even though Tenenbom doubts if He exists.

The soul is what connected him to the Hasidic Rebbes of Meah Shearim. The soul is something he writes that precedes everyone. It is the Jewish thing we all have and share, the history and fate that forms the core of who we were and remain. He notes that core takes us back to God, even if he does not believe, but the reader suspects he really does. As to a soul, he writes that the reform rabbi and her husband do not have it, not a trace of it.

This is a most interesting and entertaining book. In Careful, Beauties Ahead! Tenenbom invites you to join him on his walks through the streets and alleyways of Meah Shearim, dine with him, and drink the never-ending bottles of Coke Zero. His observations about Haredi society are not meant to be taken as authoritative but as views gathered along the way.

It is said, “You can’t go home again.” But in Careful, Beauties Ahead!: My Year With the Ultra-Orthodox, Tuvia Tenenbom shows us he never left, and that the little boy from Bnei Brak does not plan to go anytime soon.

Ben Rothke works in the information security field, and reviews books on religion, technology, philosophy, and science.