REVIEW ESSAY: Rabbi in Buchenwald; Kabbalist in Montreal

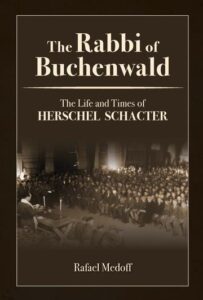

Rafael Medoff, The Rabbi of Buchenwald: The Life and Times of Rabbi Herschel Schacter (Yeshiva University Press, 2021), 512 pages.

Ira Robinson, A Kabbalist in Montreal: The Life and Times of Rabbi Yudel Rosenberg (Touro University Press, 2021), 314 pages.

Modern Orthodox Jews like to discuss rabbinic biographies. It’s a parlor game, a clever sleuthing exercise in identifying overexaggerations and adroit fact-checking. In the Yeshiva World, works about leading rabbis are held in very high regard, even as some of its leaders have warned about an inclination of authors to “stereotype” and stress the genius of their subjects without enough emphasis on the protagonist’s “hard work.”1 Books released by ArtScroll about Rabbi Moshe Feinstein and Rabbi Mordechai Gifter seem to fit this mold.2 Another on Rabbi Aharon Kotler issued by Feldheim Publishers is another within this genre.3 But the heads of ArtScroll and other publishers within the Orthodox Right ask for some forbearance, insisting that their books are meant to “inspire” and avoid any kind of criticism that, in their view, would take away from the figure portrayed in the biography.

It’s much more difficult to point out a trend among biographers within the Modern Orthodox realm. The Modern Orthodox are not anticlerical, but they have, over time, become incredulous about rabbinic biographies and stories that, to borrow from Rabbi Jacob J. Schacter’s formulation, do not always “face the truths of history.”4 In this vein, Marc Shapiro’s book on Rabbi Yehiel Yaakov Weinberg immediately comes to mind as a work that encounters the complexities of the rabbinic life.5 Shapiro traces the tensions within Weinberg’s biography, studying his transition from Eastern European Orthodoxy to the more scholarly world of Berlin. More recently, Yael Unterman’s tome on Nehama Leibowitz is a fine work about a major Jewish educator and scholar—Leibowitz eschewed any title that would have compared her role to a rabbi’s—who grappled with social and intellectual barriers throughout her important life.6 And yet, these and other examples do not target a specific readership the way that, say, ArtScroll and Feldheim, publish books for the Yeshiva World. Modern Orthodox writers and readers like to share their reading lists with a wider community of intellectually curious people.7 It is therefore probably more useful to identify the qualities of a rabbinic biography rather than a discrete canon of literature that suit the Modern Orthodox reader.

Two new biographies offer sugnificant contributions to our understanding of the rabbinic experience in North America while simultaneously teaching their readers about the exhilarating successes and the sobering challenges of rabbinic leadership. Historian Ira Robinson’s biography of Rabbi Yudel Rosenberg (1860-1935) represents an important contribution to the field. Polish-born, Rosenberg was identified as an intellectually gifted child. He was something of an itinerant rabbi, never staying very long in one place until his final stop in Montreal. Rosenberg was best known for his role in conjuring up the tales of the Maharal and his Golem. Notwithstanding, Rosenberg led a noteworthy life as a rabbi and scholar. He was one of the first to grapple with electricity and Jewish law. He wrote on kabbala and published first-rate hiddushei Torah. Rosenberg was a polemicist and ardent opponent of Reform Judaism and others who pushed for increased secular learning in Jewish schools.

Two new biographies offer sugnificant contributions to our understanding of the rabbinic experience in North America while simultaneously teaching their readers about the exhilarating successes and the sobering challenges of rabbinic leadership. Historian Ira Robinson’s biography of Rabbi Yudel Rosenberg (1860-1935) represents an important contribution to the field. Polish-born, Rosenberg was identified as an intellectually gifted child. He was something of an itinerant rabbi, never staying very long in one place until his final stop in Montreal. Rosenberg was best known for his role in conjuring up the tales of the Maharal and his Golem. Notwithstanding, Rosenberg led a noteworthy life as a rabbi and scholar. He was one of the first to grapple with electricity and Jewish law. He wrote on kabbala and published first-rate hiddushei Torah. Rosenberg was a polemicist and ardent opponent of Reform Judaism and others who pushed for increased secular learning in Jewish schools.

Rosenberg’s attempt to balance a complex combination of literary genres and a wide array of activities—like many rabbis, and in concert with the sensibilities of labor activists, Rosenberg became embroiled in the politics of the kosher butcher market—represented his own variegated adjustment to modernity. Explaining how some of the most unmodern Orthodox men, knowingly or not, participated in Jewish modernity is probably Robinson’s most important insight. Certainly, Rosenberg would not have described himself as “Modern Orthodox,” if the term had been coined (as it is used today) during his lifetime. Yet, Rosenberg’s intellectual activities, Robinson argues, are especially “modern.” In an unprecedented moment of hypermobility, Rosenberg encountered a variety of Jewish communities and thought carefully about how to interact with each group. His command of many different types of rabbinical genres enabled him to craft a multitude of authorial voices to suit his place and time. Fiction for Jewish children. Mystical works for hasidic-aligned Polish Jews. Dense rabbinical casuistry directed at his rabbinic peers and prospective lay employers.

The strategies did not always work out for Rosenberg. Robinson’s book conveys the economic challenges of the rabbinate. Unsatisfied with his rabbinic posts and unable to secure one that he perceived befit a scholar of his reputation, Yudel Rosenberg was one of many European-trained rabbis who transplanted his operations to North America in the decades surrounding the turn of the twentieth century. Robinson, with keen understanding of various rabbinic genres—halakha and kabbala, most significantly—traces Rosenberg’s career in Poland and Canada, exploring how Rosenberg’s scholarly efforts were intended to raise his career and station.

The Yudel Rosenberg biography takes both Europe and North America at full depth. Eastern Europe is not portrayed as an idyllic homeland and North America is not simply a “treifene medina” altogether unsatisfactory compared to bygone Poland and Lithuania.8 Robinson’s book challenges a scholarly supposition that the politics of the Old World rabbinate markedly differed from its counterpart in the New World. Take, for instance, historical battles between Hasidim, Mitnagdim (opponents of Hasidism), and Maskilim (adherents of the Jewish Enlightenment). These are forces that tend to occupy the thoughts and writings of Modern European Jewish historians, not Americanists. As Robinson makes clear, Yudel Rosenberg’s ties to hasidic learning and healing rituals as well as his opposition to the Haskala (his folk stories were intended to undercut attempts to offer “secular” materials to young Jews) continued in North America.

Another recent book adds to our understanding of rabbinic life in the New World. Historian Rafael Medoff’s subject, unlike Robinson’s, was no American transplant. Born in the Brownsville section of Brooklyn, Rabbi Herschel Schacter (1917-2013) led a rabbinic career that started out in the pulpit, led him to the gates of Buchenwald, back to the rabbinate in an important New York congregation, into one of the most pivotal and political agencies in American Jewish life, and finally concluded as director of rabbinic placement at Yeshiva University.

Another recent book adds to our understanding of rabbinic life in the New World. Historian Rafael Medoff’s subject, unlike Robinson’s, was no American transplant. Born in the Brownsville section of Brooklyn, Rabbi Herschel Schacter (1917-2013) led a rabbinic career that started out in the pulpit, led him to the gates of Buchenwald, back to the rabbinate in an important New York congregation, into one of the most pivotal and political agencies in American Jewish life, and finally concluded as director of rabbinic placement at Yeshiva University.

Medoff has authored several slimmer biographies on noted American Orthodox leaders.9 His Rabbi Herschel Schacter biography is the most ambitious and redounds to Medoff’s other work on the Holocaust and American Jewry. Medoff depicts Rabbi Schacter as a “natural rabbi.” As a boy in Brownsville, young Herschel was recruited to deliver speeches at neighborhood weddings “while standing on a chair.” After attending Yeshiva College and the Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary, Schacter obtained a pulpit in Stamford, Connecticut. He did not stay there long. Instead, he enlisted in the military to serve as a chaplain. The experience was the defining moment of Schacter’s career. Schacter was just twenty-seven years old when he accompanied the Eighth Corps of the Third U.S. Army to the Buchenwald concentration camp. He served as the survivors’ lifeline and rabbinic leader. As the book’s title suggests, Schacter was the “Rabbi of Buchenwald.” He was also their advocate, reporting their story to the American Jewish community, a narrative he would share throughout his long career.

Medoff smartly places the Buchenwald story as chapter 1. A skilled writer, Medoff narrates this multifaceted episode with the aid of primary sources and recorded interviews with Schacter and others. The chapter is packed with emotion while remaining a fine work of scholarship. I confess I cried at the end, requiring a few moments before returning to the biography’s second chapter to learn about Schacter’s upbringing and career. Buchenwald was the central storyline of Schacter’s rabbinic career. It moved him to take a leadership role in the Free Soviet Jewry Movement and informed how he allied himself with other Orthodox and non-Orthodox groups in social justice matters. As his biographer suggests, that broad spotlight shone on him likely made it challenging for Schacter to remain squarely within a narrower career in the synagogue. He continued a quest to help the Jewish people on a more national level as an organization executive, even as he achieved renown from the pulpit at the Mosholu Jewish Center in the Bronx. Throughout the postwar period, R. Schacter held a high station as a spokesman for Orthodox Judaism and American Jewish life while leading the synagogue until it closed its doors in 1999.

R. Schacter leads the service for the first day of Shavuot in Buchenwald, shortly after liberation. (Click to enlarge)

In fact, Schacter remained a formidable presence in the American rabbinate throughout his life. His other career benchmarks would have been monumental highlights for most other Orthodox rabbis. He was a ranking member of the Rabbinical Council of America. He led the Conference of Presidents of Major American Jewish Organizations and was brought into President Richard Nixon’s inner circle (before Watergate). Schacter leveraged his national reputation to place YU-trained rabbis and support his Orthodox cause.

Like Robinson’s work on Rosenberg, the Schacter biography throws light on the successes and challenges of the rabbinate. Medoff does not avoid the hard stuff. The reader learns about Schacter’s challenge to lead a major congregation while parenting two small children. The book covers the stakes of national leadership and advocating for a Republican presidential candidate while most American Jews—the Orthodox and other, larger groups—held a longstanding relationship to Democrat hopefuls. Medoff covers how Schacter grappled with a decision to depart from the pulpit, feeling far more compelled to serve the Jewish people within the organizational arena. Finally, the biography offers a very evenhanded understanding of how Schacter dealt with young rabbis who did not always abide by his policies and procedures, decisions that tended to work unfavorably for the younger rabbis.

The two new biographies on Rabbi Yudel Rosenberg and Rabbi Herschel Schacter cover different historical periods and utilize different scholarly lenses. The former is a fine work of transatlantic history, exploring the intellectual and cultural forces that Rosenberg encountered during his sinuous rabbinical career. The Rabbi of Buchenwald, on the other hand, is not an intellectual biography, but a work on American Jewry’s response to the Holocaust and the role of the rabbinate in American Jewish organizational life. Much more celebratory than Robinson’s work on Rosenberg, Medoff’s Rabbi Schacter biography paints an honest portrayal of a young hero-rabbi who found success and national prominence at an early age and then measured the subsequent stages of his career by that high standard. Medoff’s conclusion is that R. Schacter accomplished much during his decades in the rabbinate. His pursuit to make meaning of his various efforts will surely resonate with our own leadership ambitions and expectations for personal and professional fulfillment. The two works described here will do much more than survive the scrutiny of Modern Orthodox fact-checkers. They will call into question how the rabbinate has evolved and attached itself to various facets of modern life. Both Robinson and Medoff use their recent books to ask profound—and in their own way “inspiring”—questions about leading a Modern Orthodox life and leadership in Modern Orthodoxy.

Rabbi Dr. Zev Eleff is President of Gratz College.

- See Aharon Feldman, “Gedolim Books and the Biography of Reb Yaakov Kamenetzky,” Jewish Observer 27 (November 1994), 32-34.

- Shimon Finkelman, Reb Moshe: The Life and Ideals of HaGaon Rabbi Moshe Feinstein (Mesorah Publications, 1986); and Yechiel Spero, Rav Gifter: The Vision, Fire and Impact of an American Born Gadol (Mesorah Publications, 2011).

- Yitzchok Dershowitz, A Living Mishnas Rav Aharon: The Legacy of Maran Rav Aharon Kotler (Feldheim, 2005).

- See Jacob J. Schacter, “Facing the Truths of History,” Torah u-Madda Journal 8 (1998-1999), 200-73.

- Marc B. Shapiro, Between the Yeshiva World and Modern Orthodoxy: The Life and Works of Rabbi Jehiel Jacob Weinberg (Oxford: Littman Library, 1999).

- Yael Unterman, Nehama Leibowitz: Teacher and Bible Scholar (Urim, 2009).

- See Zev Eleff and Ethan Fabes, “The Curious Case of Jewish Intellectual Curiosity: What the Data Tells about Making an Impact in American Jewish Life,” eJewishPhilanthropy.com (July 22, 2019).

- See Arthur Hertzberg, “‘Treifene Medina’: Learned Opposition to Emigration to the United States,” Proceedings of the Eighth World Congress of Jewish Studies (1984), 1-30.

- See Rafael Medoff, “Rav Chesed: The Life and Times of Rabbi Haskel Lookstein” in Rav Chesed: Essays in Honor of Rabbi Dr. Haskel Lookstein, ed. R. Medoff (Ktav, 2009), 367-523; and Rafael Medoff, Building Orthodox Judaism in America: The Life and Legacy of Harold M. Jacobs (CreateSpace, 2015).