REVIEW: Neve Shalom on Rav Saadia

The great twentieth-century Yemenite sage and scholar, Rabbi Amram Korah (1871-1952), left behind an important work on Rav Saadia Gaon’s tenth-century Tafsir, his Torah commentary and biblical translation to Judeo-Arabic. Nahem Ilan has now produced the first full edition with useful annotations and introduction. Carmiel Cohen, in reviewing the book, shows how Ilan unlocks Korah’s gateway to the thought and writing of R. Saadia.

Neve Shalom: Perush al Tafsir Rav Saadia Gaon me-et HaRav Amram Korah, edited and with an introduction and annotations by Nahem Ilan (Yad Ben-Zvi, 2022), 711 pages

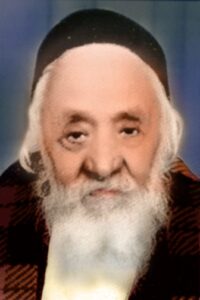

הרב עמרם קורח זצ”ל

“The sages in generations of old were accustomed to write the Torah verses with the translation of Onkelos [to Aramaic] and the translation of Rav Saadia Gaon z”l [to Arabic]. Schoolteachers were tasked with instructing the boys the Torah with these two translations, and this custom has been maintained to this day.” So states the Yemenite sage, Rabbi Amram Korah, in the opening of his commentary Neve Shalom on the Tafsir of R. Saadia Gaon. (“Tafsir,” the Arabic word for Biblical commentary—related to the Hebrew word pesher—is a reference to R. Saadia’s 10th century interpretation and translation of Tanakh.) According to R. Korah, “By the fourteenth century the light of this translation was already shining in Yemen,” and “those who strove to understand the matters of the scriptures delighted in its study and found joy in its commentary.” R. Korah (1871-1952) was the last Chief Rabbi of Sana’a, capital of Yemen, and immigrated to Israel during the great Aliya of Yemenite Jewry after the establishment of the State. Neve Shalom was written between 1938-1942 at the behest of R. Shalom Yihya Yitzhak Halevi, Chief Yemenite Rabbi of Tel Aviv, “who demanded that I send him explanations on the Tafsir,” as R. Korah recounts.

Until recently, the commentary of Neve Shalom had only been published for the five books of Humash, as well as Song of Songs, Ruth, and Ecclesiastes. Now, Prof. Nahem Ilan, dean emeritus of the Faculty of Humanities at Hemdat Academic College in the Negev, delivers an edition of Neve Shalom in its entirety. In addition to R. Korah’s commentary on the aforementioned books, this includes his commentary on Isaiah, Psalms, Proverbs, Job, Daniel, Lamentations, and Esther (none of which had been previously published). Ilan’s work is mainly based on a complete autograph of Neve Shalom and a partial draft that he received from R. Korah’s grandson, Meir Korah.

R. Korah’s interpretation was deeply appreciated by the late Prof. Yehoshua Blau, the great scholar of Judeo-Arabic and one of the leading figures in the study of R. Saadia and his biblical commentary. Ilan’s edition is published by the Ben Zvi Institute for the Study of Israeli Communities in the East, and the book’s arrival is an important contribution to our understanding of the Tafsir.

Nahem Ilan worked on his edition of Neve Shalom for about nine years. For the commentary itself, he prefaces a long and detailed introduction of about 190 pages, titled “One Thousand Years of the Tafsir,” in which he surveys a broad range of scholarship, offers many important insights about Biblical text and language, about R. Saadia’s method of translation and commentary, as well as about R. Korah’s own orientation as an interpreter of text.

R. Korah had put forth three goals for his work, as stated in the introduction: “To clarify obscurities in the Arabic translation and in R. Saadia’s writing; to cite writings by Rishonim which align with and draw on R. Saadia’s interpretations; and to examine and present [in Hebrew translation] relevant statements of worth from the sages written in Arabic” (46).

In the third chapter of the introduction, Ilan diligently surveys and categorizes the findings from R. Korah’s commentary according to topics and sub-topics. He opens with R. Korah’s comments about the biblical text, textual variants, Hebrew punctuation, morphology, literary style of the Bible, and more. After that, he presents R. Korah’s comments concerning the Arabic of the Tafsir, its punctuation, manuscript variants, text criticism, translation methods of the Tafsir, and more. In addition, Ilan lists 74 commentaries and authors that R. Korah mentions in his composition. The most prominent of these are Onkelos’ translation, Saadia’s other writings (both his biblical commentary and his philosophical treatise, Emunot veDeot), Rashi, Ibn Ezra, R. Yona ibn Janah’s Sefer Shorashim, Radak, and Maimonides’ Mishneh Torah and Guide of the Perplexed. In addition, R. Korah referred to Yemenite compositions and scholars such as his father R. Yihya Korah’s commentary Marpe Lashon on Onkelos, Me-Or HaAfela of the fourteenth century Yemenite sage R. Natanel ben Yeshaya, Midrash HaHadol, and more.

Most of the book, 455 pages, is the actual text of Neve Shalom, as edited by Ilan. The notes mainly point to the text itself, but with the helpful index (to verses, works cited, and personalities) one can also easily access Ilan’s point-by-point analysis as presented in his introduction. I must observe that the index to scriptural verses lists all references to any given verse in the introduction or where it may appear quoted in the context of a comment on a different verse. However, there is no handy way to locate the “home address” of that verse and its commentary without paging through the entire long volume until reaching the right place to discover if there is or is not accompanying commentary.

As an example of the index’s usefulness we learn that Moses’ remark about the sin of quarreling at Meriva, “From this rock [ha-min ha-sela] will we draw water for you” (Deuteronomy 20:10), appears six times in the introduction and in the text of Neve Shalom itself. Ilan cites the commentary to this verse in his introduction to make three distinct points. According to Ilan, R. Korah writes that in the Tafsir the word “ha-min” is translated as a rhetorical question and mark of bewilderment. (“Do you really think I can get water from a stone?!”) But he tries to prove that the prefix “heh” at the beginning of this word does not indicate a question and bewilderment, but rather signals “the truth of the matter.” He bases this on another version of the Tafsir text, and on the Mahaberet HaTijan (an Arabic-Hebrew grammar), and on the eighteenth-century R. Yihya Saleh who relies on a Yemenite sage of the 16th-17th centuries, R. Yihya Bashiri. To these proofs, R. Korah adds other sources where the “heh” prefix indicates the “truth of the matter” (according to Saadia, Ibn Ezra, and Radak).

An additional example from R. Korah’s commentary highlights the significance of his overall project. When the Torah mentions Laban’s two daughters, Leah and Rachel, it adds a phrase of brief description regarding each of them: “And Leah’s eyes were soft and Rachel was beautiful in form and appearance” (Genesis 29:17). Rashi’s remark is well-known: “And Leah’s eyes were soft—Because she expected to fall into Esau’s lot, and she wept, because everyone was saying, ‘Rebecca has two sons, and Laban has two daughters. The older daughter for the older son, and the younger daughter for the younger son.” Apparently, this describes a physical blemish: Leah’s eyes have suffered from the “wear and tear” of her excess tears, but it is a defect in her beauty arising from an inner, spiritual quality. Radak also suggests a physical defect, writing: “[Leah] was a beautiful woman except that her eyes were soft and tearful, but Rachel was a beautiful woman without any blemish.” On the other hand, R. Saadia translated the word as “softness,” conveying a type of gentle beauty captured in her eyes. R. Korah observes: “[R. Saadia] translated according to the intention of the scripture, as did Onkelos, rather than according to its simple meaning (peshat). Scripture aims only to describe the beauty of the foremothers, not to condemn one and praise the other.” Elsewhere R. Korah observes “the method of Onkelos and Saadia is often to aim for a translation of the verse according to its intention and not its plain reading. In many places, Onkelos and R. Saadia lay aside the Biblical language and offer an appropriate interpretive translation, which will completely differ from the biblical text and is not derived from it at all” (commentary to Genesis 39:23). This is a prominent feature of the Tafsir—many times the translation is not literal but derives from the context. (Ilan cites forty instances where R. Korah stated this.)

An additional example from R. Korah’s commentary highlights the significance of his overall project. When the Torah mentions Laban’s two daughters, Leah and Rachel, it adds a phrase of brief description regarding each of them: “And Leah’s eyes were soft and Rachel was beautiful in form and appearance” (Genesis 29:17). Rashi’s remark is well-known: “And Leah’s eyes were soft—Because she expected to fall into Esau’s lot, and she wept, because everyone was saying, ‘Rebecca has two sons, and Laban has two daughters. The older daughter for the older son, and the younger daughter for the younger son.” Apparently, this describes a physical blemish: Leah’s eyes have suffered from the “wear and tear” of her excess tears, but it is a defect in her beauty arising from an inner, spiritual quality. Radak also suggests a physical defect, writing: “[Leah] was a beautiful woman except that her eyes were soft and tearful, but Rachel was a beautiful woman without any blemish.” On the other hand, R. Saadia translated the word as “softness,” conveying a type of gentle beauty captured in her eyes. R. Korah observes: “[R. Saadia] translated according to the intention of the scripture, as did Onkelos, rather than according to its simple meaning (peshat). Scripture aims only to describe the beauty of the foremothers, not to condemn one and praise the other.” Elsewhere R. Korah observes “the method of Onkelos and Saadia is often to aim for a translation of the verse according to its intention and not its plain reading. In many places, Onkelos and R. Saadia lay aside the Biblical language and offer an appropriate interpretive translation, which will completely differ from the biblical text and is not derived from it at all” (commentary to Genesis 39:23). This is a prominent feature of the Tafsir—many times the translation is not literal but derives from the context. (Ilan cites forty instances where R. Korah stated this.)

Ilan’s significant effort and investment in making R. Korah’s commentary on Saadia’s Tafsir is evident. However, I think his contribution might have been even more accessible in at least one way that would surely have benefited those who do not read Arabic. R. Korah opens each of his comments with the Arabic word used by Saadia in his translation (as a dibbur ha-mathil), and then offers his commentary. Translating those Arabic words or phrases into Hebrew (in square brackets or in a note) would have made the intent of R. Korah’s commentary more clear. For example, before the quote regarding Leah’s eyes, we are given Saadia’s Arabic phrase for “soft” (חסנאואן). Had the Arabic been translated, readers would more clearly understand how Saadia aims for the “intention of the Scripture” in this case. Incidentally, in R. Yosef Kapah’s edition of the Tafsir, the Arabic word is translated: naot adinot (“gently lovely”). This is interesting to compare to Rashbam (the pashtan) who explained that “softness” is “lovely” (and also noted the clarity of her eyes); and the opinion of Da’at Zekenim mi-Ba’alei ha-Tosafot, who offer an etymological interpretation: “‘Soft and good’ means that she looked beautiful because her eyes were beautiful and she looked soft and girlish.”

Nahem Ilan’s own words at the end of his introduction to Neve Shalom offer the best conclusion to any analysis of this worthwhile contribution to Torah study and scholarship: “Although this is a composition from the mid-twentieth century, it makes a qualitative and unique contribution to the study of the history of the Tafsir throughout the generations, and at the same time erects a monument of honor to one of the greatest scholars to emerge from Yemenite Jewry in the last generation” (219).

Rabbi Dr. Carmiel Cohen, a staff member at the Otzar HaGeonim Project at Hebrew University, has researched and published Ralbag’s Torah Commentary (Maaliyot), and serves as a curriculum specialist for Talmud at the Henrietta Szold Institute. An earlier version of this review appeared in Hebrew in the Shabbat magazine of Makor Rishon.