REVIEW: Pathways to God

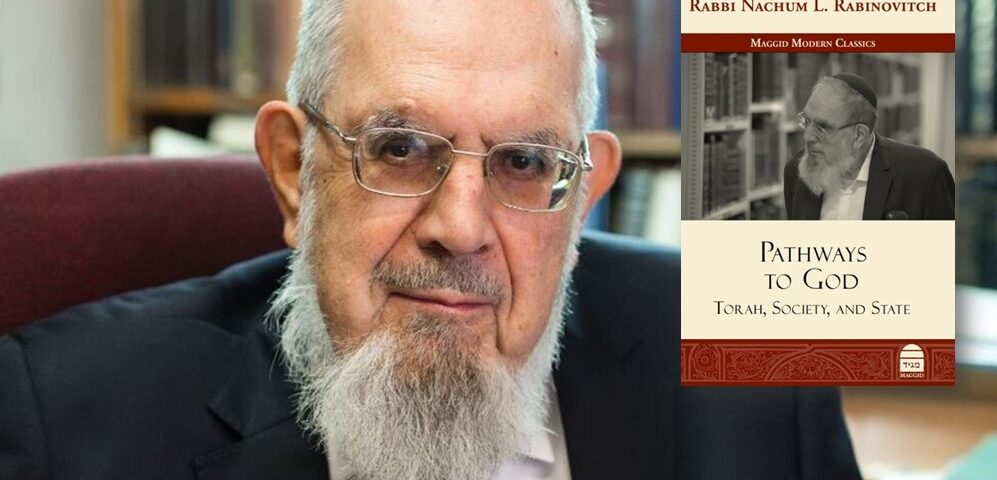

Nachum L. Rabinovitch, Pathways to God: Torah, Society, and State (Maggid Books & Me’aliyot Press, 2025).

At a moment when religious discourse surrounding the State of Israel is often marked by messianic certainty or theological retreat, Rabbi Dr. Nachum Rabinovitch’s sober, halakhic vision continues—even over five years after his death—to offer a rare and necessary alternative. A major figure in the religious Zionist world, R. Rabinovitch (1928–2020) served as a rabbi in North America and England before making aliya in 1982 to serve as Rosh Yeshiva of the Ma’ale Adumim Yeshivat Hesder. Pathways to God: Torah, Society and State is an English translation of the second half of his work Mesillot bi-Lvavam, and follows an earlier offering of his English essays, Pathways to Their Hearts: Torah Perspectives on the Individual (Maggid, 2023)—both volumes skillfully translated by Elli Fischer.

At a moment when religious discourse surrounding the State of Israel is often marked by messianic certainty or theological retreat, Rabbi Dr. Nachum Rabinovitch’s sober, halakhic vision continues—even over five years after his death—to offer a rare and necessary alternative. A major figure in the religious Zionist world, R. Rabinovitch (1928–2020) served as a rabbi in North America and England before making aliya in 1982 to serve as Rosh Yeshiva of the Ma’ale Adumim Yeshivat Hesder. Pathways to God: Torah, Society and State is an English translation of the second half of his work Mesillot bi-Lvavam, and follows an earlier offering of his English essays, Pathways to Their Hearts: Torah Perspectives on the Individual (Maggid, 2023)—both volumes skillfully translated by Elli Fischer.

In the first volume of Pathways, R. Rabinovitch explains that the work as a whole is structured in accordance with Maimonides’ assertion that the Torah has two overarching goals: the “welfare of the soul” and the “welfare of the body” (Guide III:27). The former refers to the acquisition of correct beliefs by the individual, while the latter concerns the regulation of social life and prevention of injustice. While the soul is ultimately superior, the body is prior in nature and time, as a functioning society is a prerequisite for spiritual attainment. In keeping with this, Pathways to Their Hearts addressed the individual while the present volume focuses on society at large, with particular attention to the State of Israel. Half of the book’s twelve chapters deal directly with matters pertaining to statehood, including the religious significance of the State, the nature of its authority, and the relationship between Judaism and democratic society. Other chapters include an outline of Torah-based economic policy, the status of women and a dialogue between R. Rabinovitch and his student, R. Jonathan Sacks.

Elsewhere I have analyzed at length R. Rabinovitch’s view of the structure and proper functioning of the state according to Torah principles. Here I focus more narrowly on his understanding of the religious significance of the State of Israel as articulated in the second volume of Pathways.

R. Rabinovitch rejects both the theology of mainstream religious Zionism, which views the State as a clear part of the messianic process, as well as the contemporary Haredi view that denies it intrinsic religious value. Instead, he sees the establishment of the State of Israel as a unparalleled opportunity to renew Jewish life within a comprehensive societal framework and in doing so realize the Torah’s highest aims: “the ingathering of the exiles, the building and cultivation of the land, and the fashioning of a just society that sanctifies God’s name for all peoples to see” (26). His position should be understood in light of Rambam’s identification of “welfare of the body” as one of the Torah’s two purposes. Since it can be achieved only by “means of political organization,” the founding of the State of Israel constitutes not merely an historical event but a halakhic one: an opportunity to apply the Torah to all dimensions of life—individual, social, and national.

The unique challenges posed by renewed Jewish sovereignty after two millennia meant that fundamental religious questions regarding the State remained unanswered. To address them, R. Rabinovitch turns to three historical precedents: the return to Zion during the Babylonian Exile, the establishment of Hanukka, and the Bar Kokhba rebellion. He emphasizes that though the challenge of how to respond to the founding of the State is compounded by the “absence of explicit divine guidance,” faithful Jews are “not exempt from the duty to reach decisions and act on them” (10, 11). In this, he continues a central idea found throughout the first volume of Pathways as well, the importance of personal responsibility in the service of God.

The return to Zion, as described in Ezra and Nehemiah, was initially disappointing. Only a minority returned, religious standards were low, intermarriage was widespread, and the rebuilt Temple lacked the Divine Presence. Against this backdrop, R. Rabinovitch reads the Talmudic statement that the Men of the Great Assembly, who witnessed the Return to Zion, “restored the crown to its former glory” (Yoma 69b). According to the Talmud, Jeremiah and Daniel could no longer speak of God as “awesome” (nora) and “mighty” (gibbor) amid the destruction and enslavement they beheld. The Men of the Great Assembly, however, reinstated these epithets. They understood that “the restoration of a semi-autonomous Jewish polity, however limited its dimensions, is a real manifestation of God’s might” (15). For R. Rabinovitch, this insight applies with even greater force after the Holocaust. While the rebirth of Israel does not compensate for the horrors of the past, those who witnessed the ingathering of exiles and the renewal of Jewish national life may rightly proclaim divine might and awesomeness. In this way, despite its imperfections, the State of Israel restores God’s crown.

While R. Rabinovitch aligns with mainstream religious Zionism in affirming the religious value of Jewish sovereignty, he diverges sharply when it comes to the messianic question. While the State of Israel represents the “beginning of redemption” (athalta de-geula) for most Religious Zionists, R. Rabinovitch rejects such certainty, and insists that only a prophet can make such determinations. Likewise, appeals to rabbinic statements about the redemption often rest on superficial readings. As an example, he points to the Talmudic dictum (Sanhedrin 98a) that there is no more obvious sign of the End of Days than the “mountains of Israel yielding their fruit to the Jewish people” (cf. Ezekiel 36:8). The point of this drasha is that these developments are necessary conditions for the redemption, not proof that it has arrived.

It is noteworthy that R. Rabinovitch cites this specific Talmudic statement. It is frequently invoked in Religious Zionist circles, in no small part because R. Avraham Yitzhak HaKohen Kook himself made use of it, stating that the “beginning of redemption” was underway “from the moment the obvious sign of the End of Days had appeared” with Israel returning to the land and reaping its fruits (Iggerot HaRa’aya III:871). For his part, however, R. Rabinovitch stresses “that God’s salvation of the Jewish people is not measured with the yardstick of the End of Days” and therefore the “significance of the State of Israel is not limited… to its being a stage in the process of redemption, even as we pray that it indeed will be so” (19, 23). It is worth mentioning that this view echoes ideas articulated by R. Joseph B. Soloveitchik and R. Aharon Lichtenstein who likewise affirmed the profound religious significance of the State without assuming it to be part of the messianic process.

That the religious significance of Jewish autonomy is unrelated to the messianic question is, according to R. Rabinovitch, the deeper lesson which can be learned from the establishment of Hanukka. Based on close reading of Rambam (Hilkhot Megilla ve-Hanukka 3:1–3) and his Talmudic source, R. Rabinovitch highlights that Sages waited a period of time before instituting the celebration of holiday—as they did not at first know if the victory was complete and the war had in fact ended. Moreover, Hannuka is celebrated even though it did not lead to the final redemption and the Temple was eventually destroyed. So too, the modern deliverance of the Jewish people and return to our homeland can unequivocally be seen as “God’s salvation, even if we cannot yet say with confidence that this is the long-awaited final redemption” (19).

R. Nachum Rabinovitch זצ”ל

Finally, the Bar Kokhba rebellion offers a cautionary example. R. Akiva believed Bar Kokhba to be the Messiah based on his military success, yet the revolt ended in catastrophe. The ultimate lesson is that “[e]ven when we have facts, we must interpret them cautiously” (20). Based on the manner in which Rambam describes the Messianic king and the Messianic era (Hilkhot Melakhim, ch. 11–12), R. Rabinovitch argues that human responsibility remains paramount, and that national success must not be read as “an incontrovertible sign that the present redemption is unstoppable” or that “we, unlike generations past, are immune to the charms of false messiahs” (23). Such hubris, he warns, may “cause people to think they can do all kinds of things without the need for prudence or discretion” (16).

R. Rabinovitch’s guarded approach toward theological readings of history runs counter to popular trends. For example, a pamphlet recently published by R. Yosef Tzvi Rimon reads the events of Israel’s current war as “puzzle pieces in the hand of God,” concluding that the wartime slogan “together we will win” should now be “together we have won.” It can only be speculated how R. Rabinovitch would have responded to this particular work, but in Pathways he argues forcefully against such claims of certainty. He cautions that the “pretentiousness of giving unequivocal interpretations of history is liable to backfire or lead to irresponsible decisions” (21).

R. Rabinovitch can also be seen here rejecting what has become a further cornerstone of messianic thought: that the unfolding of redemption cannot be halted. He warns that the notion that we are in the midst of a “surefire, unstoppable process of redemption is an unparalleled delusion” (16). The gap between his stance and ideas that have become dogma within Religious Zionism can be illustrated by pointing to the oft-told story in which R. Yitzhak Halevi Herzog dismissed advice not to return to Palestine during World War II, insisting that “the prophets foretold only two destructions, not a third.” R. Rabinovitch’s position runs directly counter to the eschatological certainty implied by this account. Rather than grounding practical decisions in religious guarantees, he consistently emphasizes personal responsibility, insisting that “we have the power to choose, and therefore we are responsible for our own fate” (23).

While he dismisses messianic certainty, R. Rabinovitch equally rejects the view that the State’s value lies merely in providing physical refuge: “For the believer, there is a religious need and a religious value in having a total societal framework in which the Torah can operate” (26). As noted previously, this should be understood in the context of Rambam’s definition of “welfare of the body” as a central goal of the Torah and its commandments. The State provides the social and political platform which is required for this and therefore “makes possible the fulfillment of the Torah’s greatest aims: the ingathering of the exiles, the building and cultivation of the land, and the fashioning of a just society” (26). Here too, R. Rabinovitch continues a theme he develops at length in the first volume of Pathways, namely that the Torah establishes overarching aims for the Jewish people that are broader than the contours of any particular mitzva.

From this ideological foundation also flow concrete obligations. Religious Jews have a duty to share in the “public burden,” particularly IDF service and economic activity (34). R. Rabinovitch goes so far as to say that the choice to “withdraw to the margins of Israeli society” and “retreat from participation in the Jewish state” is tantamount to a “denial of the very basis of halakha” (30). This is because failure to engage with the State is in fact a failure to work towards that central halakhic aim of “welfare of the body,” which is most fully achieved through the State.

Though he does not mention Haredi society by name, R. Rabinovitch calls out those who espouse a Torah-only ideal in order to “justify shirking their responsibility to provide for their families and to contribute to the economy, society at large, and national defense” (35–36). Regarding such a notion, he invokes the Sages’ declarations that one who has “only Torah” has neither Torah nor God (Yevamot 109b; Avoda Zara 17b). R. Rabinovitch, of course, passed away a few years before the outbreak of the October 7th war. However, his pointed criticism of Haredi ideology carries added weight in light of ongoing Ultra-Orthodox refusal to serve in the IDF even as the nation’s defense and manpower needs become more acute. R. Rabinovitch repeatedly chastises those who “regard the Torah as the private property of a marginal social group … [and are] unaware of the needs of others and inattentive to their concerns” (36). For him, this is the antithesis of what Judaism demands of us and indeed what much of this volume of Pathways is dedicated to: “public responsibility and a broadminded Torah approach” (37).

Rami Schwartz is a senior researcher at the Knesset Research and Information Center.